February 15, 2023

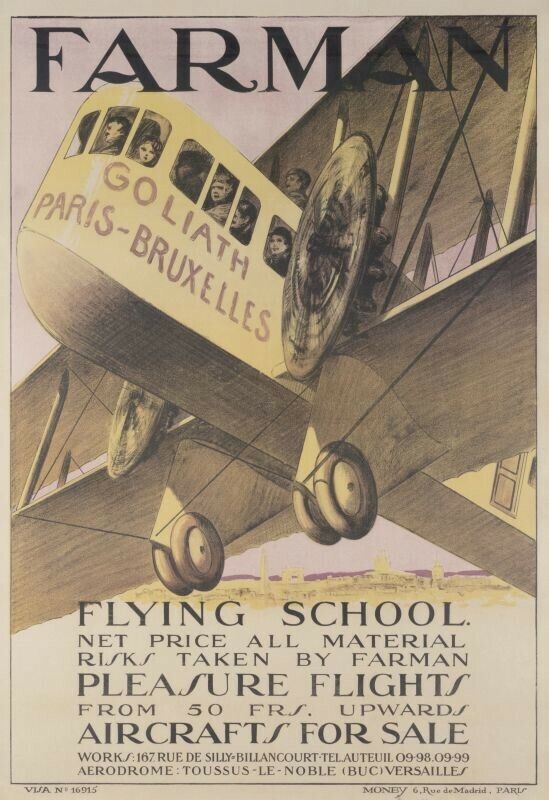

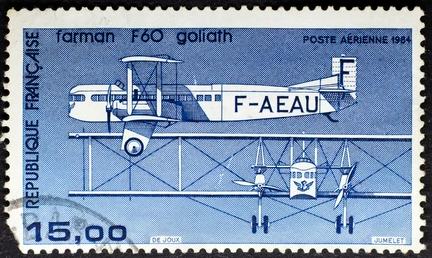

Today in Microsoft Flight Simulator, I’ll be flying the Farman F.60 Goliath, the world’s first civilian passenger airplane, on its historic route from Paris to London.

And to tell this story, I’m using a mod that recreates the two airports, Le Bourget and Croydon, as they looked in the 1930s. Le Bourget (below) was the airport where Charles Lindbergh landed in1927.

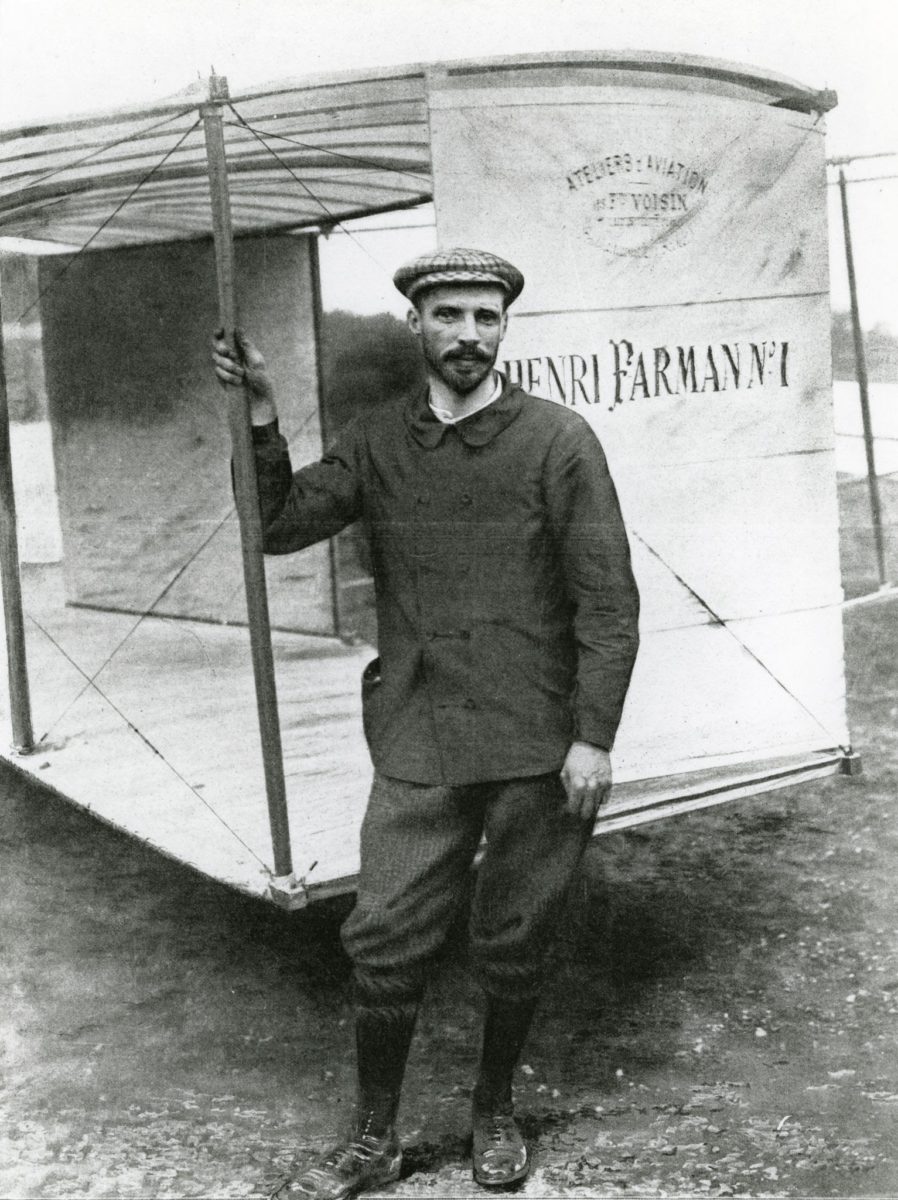

Henri Farman was born in 1874, the son of a English couple living in Paris, France (his father was a reporter for a London newspaper). Originally he trained at the École des Beaux Arts as a painter.

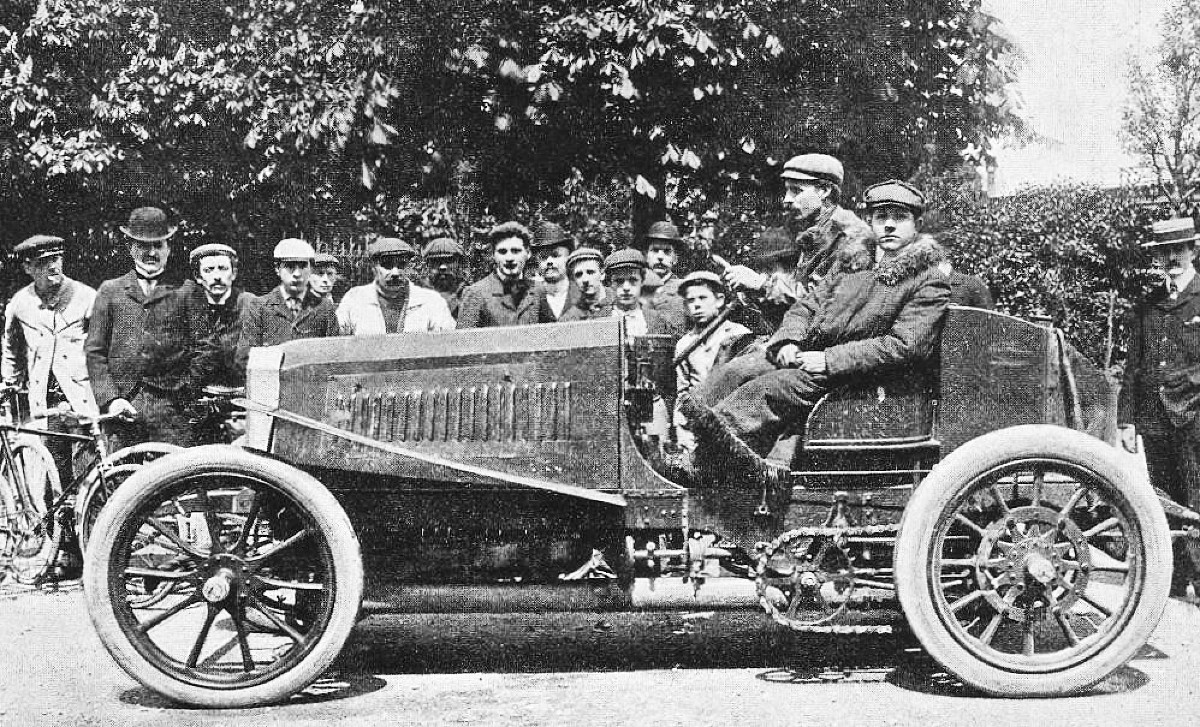

He quickly became caught up (like the Wright Brothers and Glenn Curtiss) in the bicycling craze. Along with his younger brother Maurice, he became a champion bike racer.

The two brothers soon graduated to auto racing, winning several early cross-country races.

In 1907, Henri purchased an early biplane from the pioneer aircraft designer Gabriel Voisin, and flew it to set new records for height, distance, and endurance.

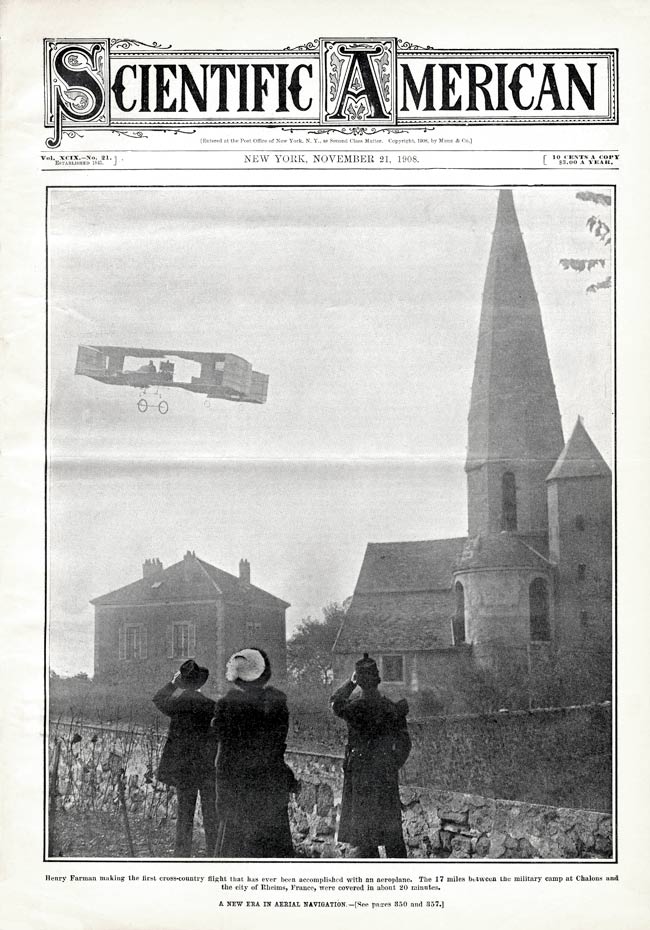

The next year, Henri Farman made the first cross-country flight in Europe, a distance of 27km to Reims. He competed in early races and airshows, and opened a flying school at Châlons-sur-Marne.

After a falling out with Voisin, Farman began designing his own airplanes. He and his two brothers, Maurice and Dick (who tended to the business side founded their own aircraft company, Farman Aviation Works, near Versailles.

His designs became known for popularizing the aileron (French for “little wing”) to induce roll, rather than the “wing warping” technique used by the Wright Brothers.

Farman produced several “pusher” planes (with the propeller behind) that proved popular in the early days of World War I. As the war progressed, however, they lost ground to other designs.

In 1918, Farman was busy developing a new two-engine heavy bomber that could carry 1,000 kg (2,200 lbs) of bombs out to a range of 1,500 km (930 miles).

When the war abruptly ended, however, the Farmans realized their monstrous new biplane – dubbed the “Goliath” – might find new purpose transporting civilian passengers on new air routes through the sky.

The Farmans formed their own airline and on February 8, 1919 – just a few months after the Armistice – flew 12 passengers from France to England and back the following day. Because non-military flying was not yet authorized at that point, they were all ex-military pilots on orders.

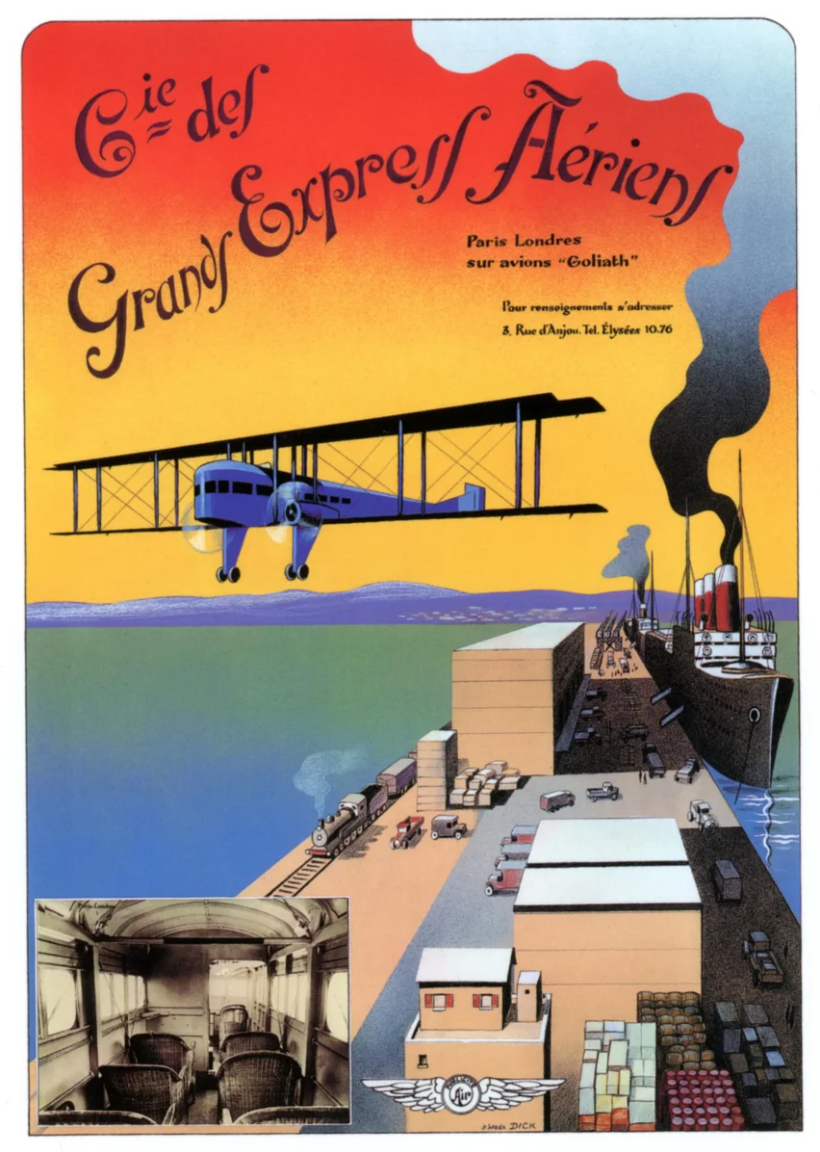

By 1920, a new airline, the Compagnie des Grands Express Aériens (CGEA), acquired several Goliaths and began offering scheduled flights – for civilians now – from Le Bourget airfield outside of Paris to Croydon airfield near London.

Here is one of their planes, nearby on the tarmac at Le Bourget. Note the registration number, F-GEAD, because it will come up again later.

A competing airline, Compagnie des Messageries Aériennes (CMA), also flew the same London-Paris route using Goliaths, and more airlines quickly emerged flying routes to Brussels as well.

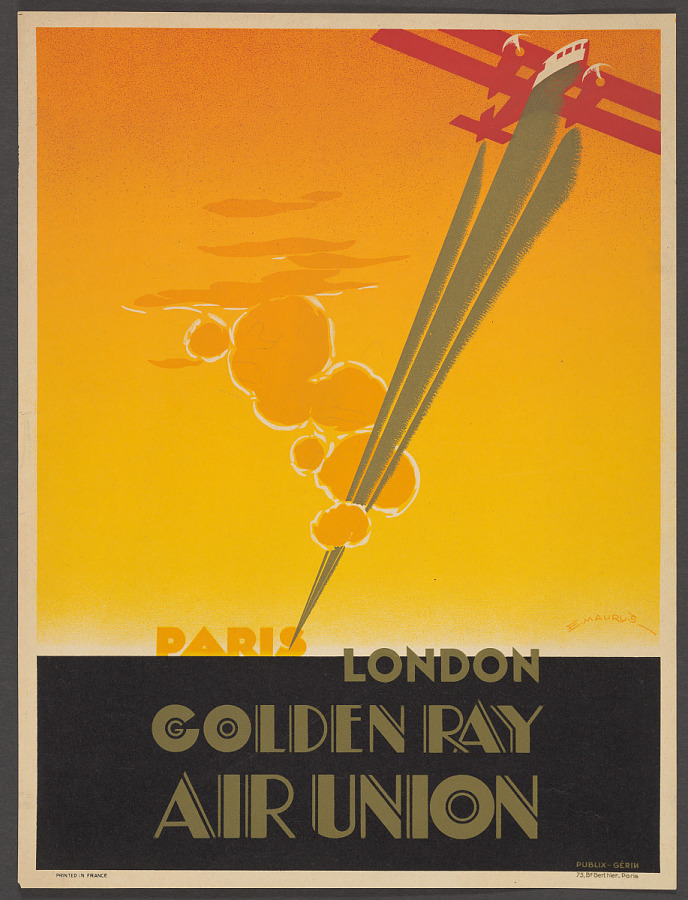

In 1923, CGEA and CMA merged to form Air Union. It’s one of their Goliaths we’ll be boarding today, bound for Croydon.

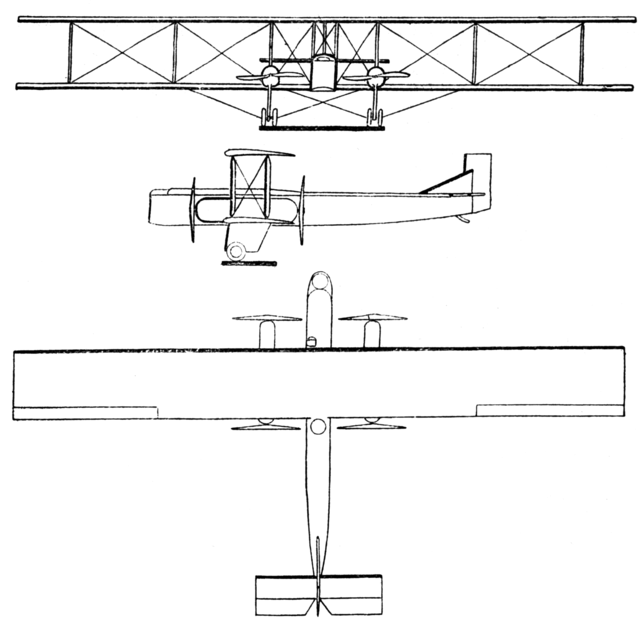

The wingspan of the Goliath is almost 87 feet, compared to 93 feet for an original Boeing 737. The total area of both wings is 1700 square feet, compared to 978 for the 737’s single wing.

Its length, from nose to tail, was a most modest 48 feet (versus 94 for the 737). Like most planes of its time, the Goliath was constructed of a wooden frame covered in fabric.

As a result, despite its large size, the Goliath had an empty weight of just 6,393 lbs., one-tenth that of a 737 (which weights in at 62,000 lbs).

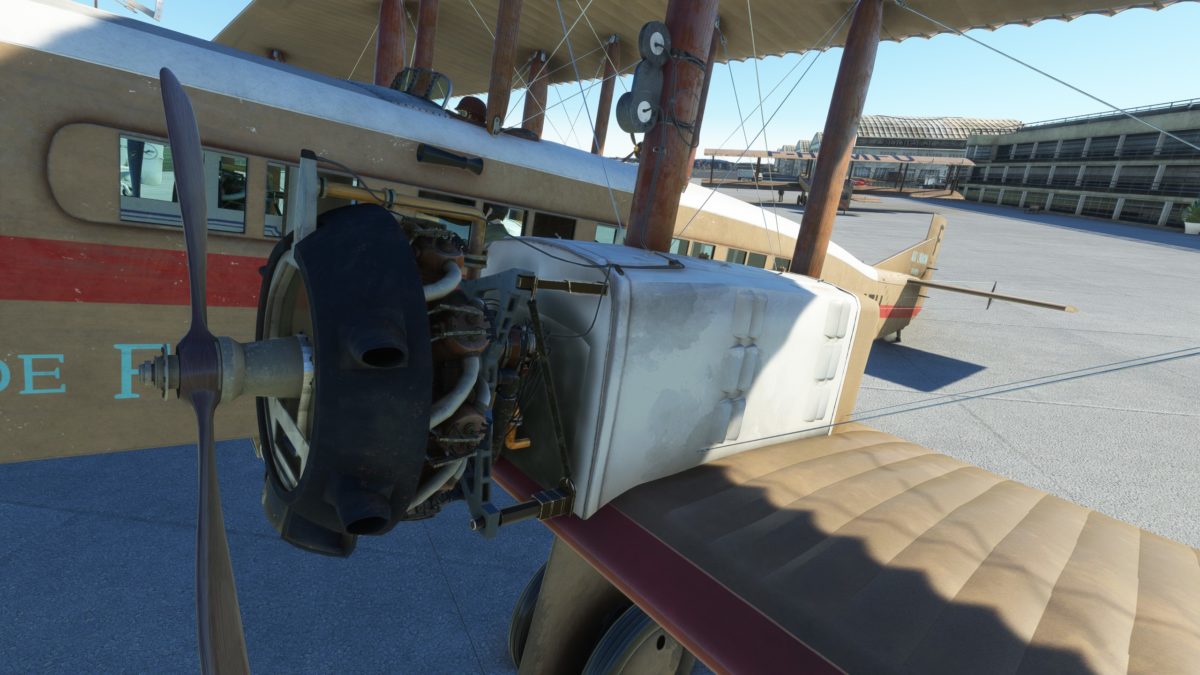

The Goliath was driven by two Salmson 9Z water-cooled 9-cylinder radial engines, producing 250 horsepower each. They only had a useful life of around 100 hours.

So where’s the cockpit? It’s actually on top of the fuselage, open and exposed to the elements.

The pilot sat on a kind of elevator platform in the middle of the passenger cabin. Beside him, slightly lower and to his right, sat a flight engineer.

To the pilot’s left was the throttle and mixture control for each of the Goliath’s two engines.

To either side, directly above each engine, were gauges showing oil temperature (above) and pressure (below) for each.

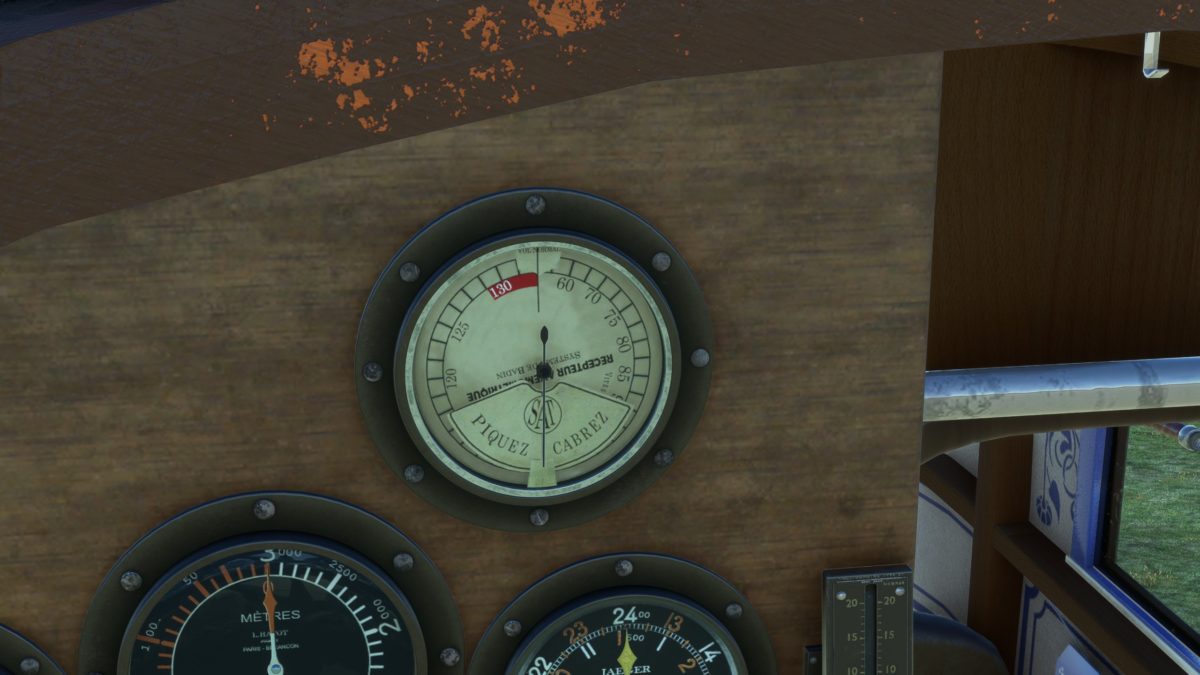

The main instrument panel features an altimeter (in meters) in center. On either side are tachometers showing RPM for each engine, with their respective fuel gauges and gold magneto selectors below.

The airspeed indicator bears a closer look. It show km/hour, and highlights the “danger zone” of flying any faster than 130 km/hour (70 knots). The lower needle indicates the aircraft’s pitch: “piquez” for nose down, “cabrez” for nose up.

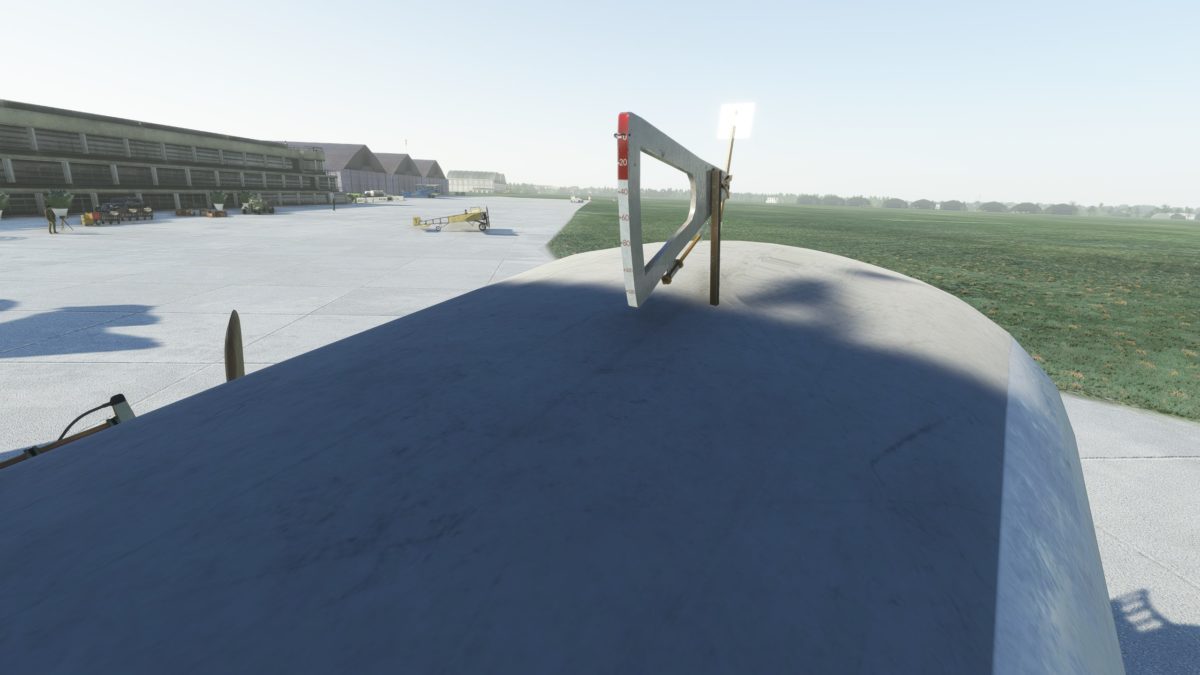

There is another device on the aircraft’s nose, actuated by the oncoming airflow, which also appears to measure airspeed.

Behind the cockpit is a small propeller, which spins from the oncoming airflow and drives a generator for electrical power.

Its time for the passengers to board. The best views are in the forward cabin, in front of the cockpit.

There is a direct access door to the front, but it’s looking a bit precarious.

Maybe it’s better to board everyone from the back.

Between the forward and rear portions of the cabin, the Goliath seats 12-14 passengers.

Here are some real photos of people boarding a CGEA flight, and of the Goliath’s cabin interior.

There were daily scheduled flights, and they weren’t cheap. I haven’t been able to find a price for Paris to London, but a London-Paris-Marseille combined ticket in 1922 reportedly cost £17.17. That was $76.75 at the time, equivalent to $1,356 today.

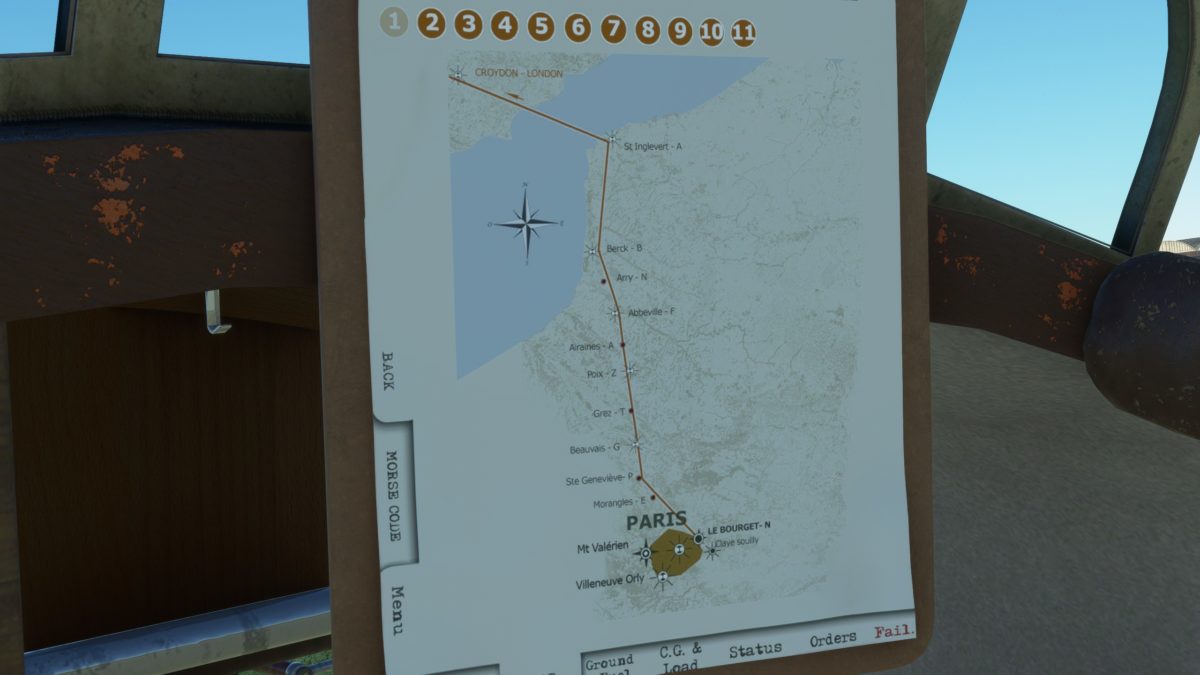

Our authentic route today will take us north from Paris across Picardy to the narrowest crossing point of the English Channel, near Calais, then on to Croydon, just south of London. The flight will take about two and a half hours.

With a cough and a belch of smoke, I start the engines one at a time.

Le Bourget (LFPB) opened in 1919, and remained Paris’ only airport until Orly was built in 1932. It remained a commercial airport until 1980, and continues to serve private aviation today – though it looks a lot different.

Rather than distinct runways, the grassy field (at this time) is demarcated with striped lines into four parallel and adjacent strips. I’ll be taking off on the one closest to the terminal.

The Goliath takes some time to get going, but with its huge wings, begins to lift off at just 75 km/hour (40 knots, some 15 knots slower than the typical takeoff speed of a Cessna 172).

This morning is quite foggy, which could create challenges. The Goliath has no gyroscopic instruments, and must rely on visual reference points.

That means no flying at night or in heavy clouds. Conditions like these make it difficult to see the horizon clearly and remain straight and level.

In theory, the Goliath has a service ceiling of 18,000 feet, and even took passengers up to 20,000 on some early demonstration flights. In practice, it usually flew close to the ground – at just 500 or 1,000 feet – in order to navigate.

A half-hour later, as I continue north over Picardy, the visibility has improved quite a bit.

That’s fortunate, because on a foggy day on April 7, 1922, this route – this exact location, in fact – was the scene of the first midair collision in airline history.

Remember the blue Goliath, F-GEAD, operated by Compagnie des Grands Express Aériens (CGEA) that I pointed out on the tarmac at Le Bourget? That day, it was flying three passengers to Croydon.

Suddenly, out of the mist, appeared a De Havilland DH.18 carrying air mail in the opposite direction on the same route, at the same low altitude.

Neither pilot had time to take any evasive action. They collided, and both airplanes crashed. A total of seven people (four crew plus three passengers) were killed.

Following the incident, several airlines held a meeting at Croydon and agreed on three basic rules: First, all airplanes meeting head-on should give way to the right. It’s a rule that’s still followed today.

Second, all airliners should be equipped with radio, to communicate with each other. Third, all new airliners should provide the pilot with a clear view forward – something neither plane, with their cockpits perched above a bulky cabin, really had.

I’ve reached the mouth of the River Somme on the Channel coast. There are still some fog banks ahead.

I follow the French coastline north for almost an hour. Passing over Wissant, it’s time to turn northwest and cross the English Channel.

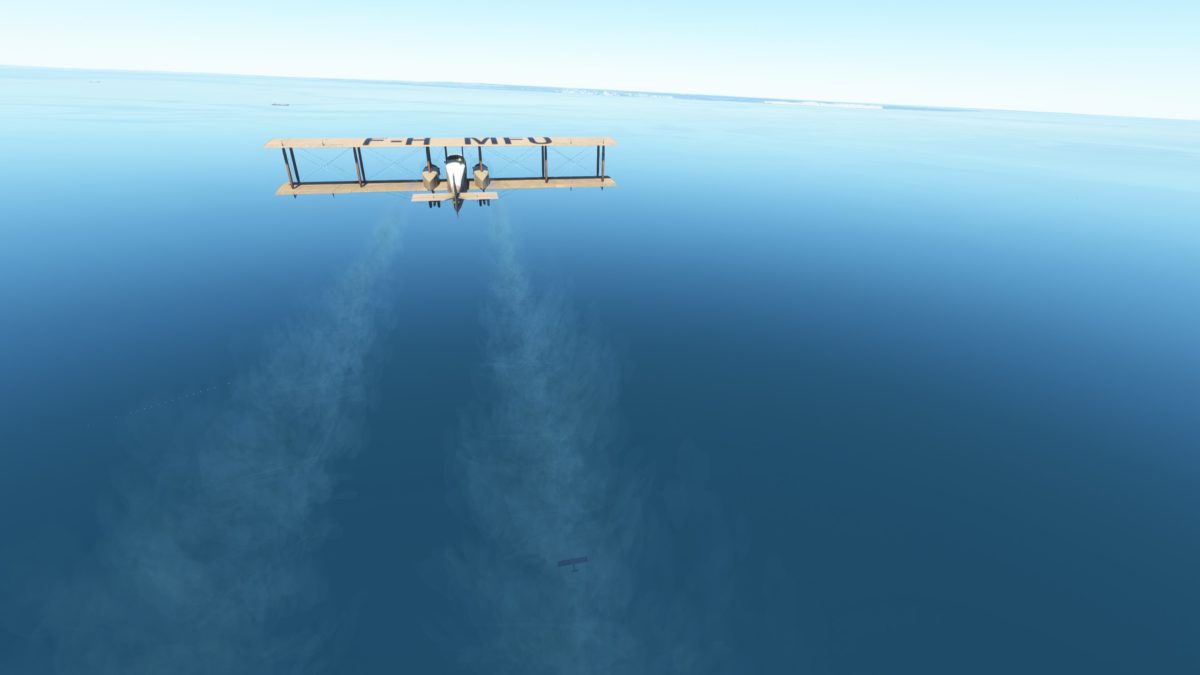

Notice the grey smoke trailing behind me. In the Goliath, that’s a sign I’ve set the fuel mixture too rich. It won’t cause us any immediate problems, but it will waste fuel and gunk up the engine longer-term.

So I’ve pulled back the mixture control a bit, and it seems to have solved the problem.

From this angle, the Goliath looks like a hawk with its talons outstretched to grab a fish.

With clear weather, the White Cliffs just west of Dover made an easy aiming point, clearly visible for many miles out.

It’s still a relief to make landfall, near Folkestone. The Goliath is notoriously prone to breakdowns, and over the 33km (20-mile) Channel crossing, there’s nowhere to land.

I’ve kept a close eye on my oil temperature and pressure the whole way. Run these engines for too hard, for too long, and they’ll give out.

It’s still almost another hour over the chalky English countryside, and the weather is starting to get cloudy again.

I’m plugging along at about 110 km/hour, or 60 knots, to avoid overheating the engines. Keeping an eye on them here, from my perch in the cockpit.

As I get closer to Croydon, just after noon, the clouds start closing in.

At least I’ve spotted the airfield. It’s that large patch of green straight ahead.

Croydon was opened in 1920. It served as London’s main airport until World War II, when it was converted into an RAF fighter base. After the war, it was surpassed by up-and-coming Heathrow.

Croydon was the first airport in the world to introduce a control tower and Air Traffic Control procedures, starting in 1920. It was also the first to adopt “Mayday” as a recognized distress call, from the French “M’aidez” meaning “help me”.

I’m barely able to discern the two crisscrossing runways from the wear marks in the grass. I’m circling the airport until I can figure out which one the wind favors.

Landing the Goliath is proving tricky. It needs to come in very slow. But even when I pull the throttle back to idle, it tends to gain a dangerous amount of speed in any descent.

On my first try, I realized I was coming in way too fast and decided to go around and do another attempt.

Coming around for another try, with the airport on my left, trying to keep it low and slow.

On try #2, I’m still faster than I should be, but hoping I’ll have enough room to slow down and land on the flare.

Forget about centerline, I’m just happy to be on the ground.

Welcome to London. Please proceed to passport control.

The Farman Goliath had a surprisingly long life as an airliner, being retired only 1931 with the coming on new all-metal airliners such as the Junkers Ju 52 (visible behind it).

The Farman Goliath evokes an era when flying felt daring because it was daring. It was an expensive and dangerous gamble on a brand new technology, for the select few.

Despite this, new air routes sprang up across Europe, taking people from city to city with unprecedented speed, and at least as much comfort as they could manage.

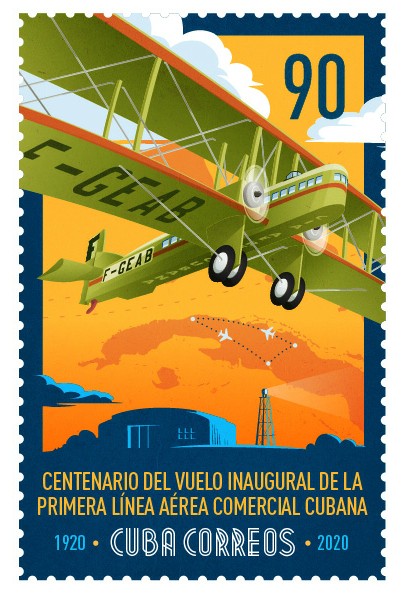

Cuba’s first airline, the Compañía Aérea Cubana (CAC) bought six Farman Goliaths, transported there by ship in 1920. It soon went out of business, but is heralded as the beginnings of aviation in that country.

The F.60 Goliath was also adopted by several countries – including Belgium, Czechoslovakia, France, Italy, Japan, Peru, Poland, the Soviet Union, and Spain – in its original military role as a bomber.

Approximately 60 Goliaths were built. No complete airframe exists today. Only the fuselage of the airplane we just flew, F-HMFU, survives on display at Le Bourget.

Air Union was eventually merged with four other French airlines in 1933 to form Air France. Farman Aviation Works was also nationalized in 1936 as part of Société Nationale de Constructions Aéronautiques du Centre (SNCAC).

The three Farman brothers largely retired after their company was nationalized, and continued living in France until their deaths in 1940 (Dick), 1958 (Henri), and 1964 (Maurice).

I hope you enjoyed this introduction to the Farman F.60 Goliath, the bomber-turned-airliner that first introduced the world to commercial aviation.

Leave a Reply