August 14, 2019

This is a post about my visit in the summer of 2019 to Tuskegee University, in eastern Alabama, which was an opportunity to learn about two amazing Americans and the legacy they left behind.

Those two individuals are Booker T. Washington, the founding president of the school, and George Washington Carver, a scientist he recruited to study and teach there.

Booker T was born a slave in 1856 in remote western Virginia, where he later wrote of growing up in abject poverty and ignorance.

After Emancipation, Booker and his family went to West Virginia, where he labored as a child in the salt mines there. In the evenings, he gathered a small library of books and taught himself to read.

When Booker signed up for grammar school in West Virginia, they asked him his surname. He didn’t have one, so he adopted the name “Washington” after the first American president.

In 1872, at the age of 16, Booker T. Washington walked across Virginia to enroll at the Hampton School (now Hampton University), a school set up to teach freed slaves. He worked as a janitor there to pay his way.

Hampton was founded by former Union General Samuel C. Armstrong. Born to a missionary family in Hawaii, Armstrong led an African-American unit in the Civil War and afterwards joined the Freedmen’s Bureau. He earned Booker T’s lifelong admiration.

The curriculum at Hampton focused on practical skills (like bricklaying, below) as well as personal hygiene and manners – a focus that had a major influence on Booker T’s thinking. Booker himself emerged as an accomplished speaker, and returned to Hampton as a teacher.

In 1881, some sponsors in Alabama asked Armstrong to recommend a White educator to become the principal of a new school for Blacks they were setting up at Tuskegee. Instead, Armstrong strongly endorsed 25-year old Booker T. Washington for the job, and the sponsors accepted.

When Booker T arrived at Tuskegee, his school had almost no resources. He taught his students brick making so they could construct their own school buildings. To this day, you can see their thumbprints in the bricks they made.

To keep the school going, Booker T. Washington traveled and spoke all across the country to raise money.

He wrote a best-selling book, “Up From Slavery”, telling his own life story and the philosophy of practical “racial uplift” it shaped.

Booker T. Washington’s book impressed wealthy White donors like oil magnate John D. Rockefeller and steel tycoon Andrew Carnegie, who paid for new buildings to be constructed on Tuskegee’s campus.

In 1900, Tuskegee students built The Oaks, an impressive home on campus for Booker T. Washington to work and entertain wealthy and important guests.

The comfortable parlors on the ground floor of The Oaks are where Booker T. Washington entertained many of the wealthiest and most famous men of his day, to persuade them to donate to Tuskegee.

His private study upstairs at The Oaks was where Booker T. Washington wrote and worked.

On the walls of his study, Booker T. Washington hung portraits of people he admired. Farthest left is Frederick Douglass. Next is Alexander Pushkin, the Russian poet whose great-grandfather was African. To the far fight is Andrew Carnegie, one of Tuskegee’s donors.

On another wall are Booker T. Washington’s degree from the Hampton Institute, as well as honorary degrees he received from Harvard and Dartmouth.

And on yet another wall are portraits of the US Presidents he came to know and became good friends with: Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft.

In fact, in October 1901, President Roosevelt invited Booker T. Washington to dine with him at the White House – the first African-American to receive such an invitation. It sparked a nationwide controversy and an angry political backlash.

The dinner and the controversy inspired African-American composer Scott Joplin, the “father of ragtime”, to write an opera titled “A Guest of Honor”.

Booker T. Washington was not without his critics. Some charged that, in order to woo wealthy donors like Andrew Carnegie (below), he catered too much to White sensibilities and that his philosophy of “self help” downplayed the injustices faced by African-Americans.

In particular, W.E.B. Du Bois, who helped found the NAACP, argued that Washington’s focus on practical – sometimes menial – skills and good manners neglected the need for political action to assert African-American rights, and accepted second-class status.

Critics saw Booker T. Washington’s earnest exhortation to fellow African-Americans to “be clean, industrious, and do a job well, and the South will make a place for you” as dangerously naive at a time when lynchings were commonplace.

But Washington saw himself first and foremost as an educator, laying the foundation for future progress. He was convinced that illiterate former slaves could never win equality without developing valued skills and, with them, self-respect.

Booker T. Washington brought a number of first-class teachers, researchers, and administrators to Tuskegee, including two women who he eventually married.

After his first wife died in 1884, Booker T married Olivia A. Davidson, a fellow graduate of Hampton, who he recruited a teacher and eventually Vice Principal at Tuskegee. She was an intelligent and much-prized help-mate, but died soon after a fire in their home in 1889.

In 1893, he married Margaret Murray, who eventually became Lady Principal at Tuskegee and who everyone describes as “formidable”. By all accounts, she was a tough and determined woman you didn’t fool with.

Booker T also recruited Josephine Bruce, the widow of African-American Senator Blanche Bruce (R-MI), to teach high-class deportment and manners to the female students at Tuskegee. She also eventually became the school’s Lady Principal.

But the most famous person Booker T. Washington recruited to Tuskegee’s faculty was undoubtedly the agricultural scientist George Washington Carver, whose life story he shared much in common with.

A National Historical Site devoted to George Washington Carver is located in an old campus laundry building across the street from Washington’s home, The Oaks. It’s well worth a visit.

George (he was just George then) was born a slave in rural Missouri sometime in the early 1860s. During the Civil War, he, his mother, and his sister were kidnapped by Confederate raiders, and only baby George was eventually recovered.

After Emancipation, young George was adopted by his former owners, Moses and Susan Carver, and raised as their own in this small farmhouse in Missouri.

Little George Carver was a very curious and intelligent boy who liked to wander the countryside for hours looking at and collecting the rocks and plants he encountered.

He also had a gift for drawing. All on his own, George discovered soils that he could grind into different pigments to color his drawings.

George Carver wasn’t allowed to go to his nearest school, so he traveled to a nearby town and slept in a barn while learning how to read and write. He kept his first school slate for the rest of his life.

Like Booker T, George adopted the name Washington as a symbol of his freedom. He was also inspired by his teacher’s words: “You must learn all you can, then go back out into the world and give your learning back to the people”

George Washington Carver applied and was accepted to Highland University in Kansas. But when he showed up, they realized he was Black and refused to admit him. He had to spend many years working in odd jobs and manual labor on farms. But he kept his first typewriter with him.

Eventually Carver was able to study art and music at Simpson College in Iowa. But his art teacher recognized his talent for drawing plants, and encouraged him to study botany at Iowa State University, where he graduated in 1894.

In 1896, Booker T Washington recruited George Washington Carver (front and center) to head the Agricultural Department at Tuskegee.

Carver taught at Tuskegee for 47 years and developed his department into a leading research center. The building that housed his laboratory is still in use today.

Before leaving for Tuskegee, his colleagues at Iowa State gave Carver this microscope, “which he kept as a treasured gift”.

Carver’s ingenuity seemed to know no bounds. He developed methods of crop rotation to increase productivity, as well as new foods and products derived from dozens of different crops.

Drawing on his childhood experiments as a budding artist, he developed new color pigments for paints that the poor farmers in the countryside around Tuskegee could afford.

And, of course, there was the peanut. (Peanut plant outside the George Washington Carver National Historical Site a Tuskegee)

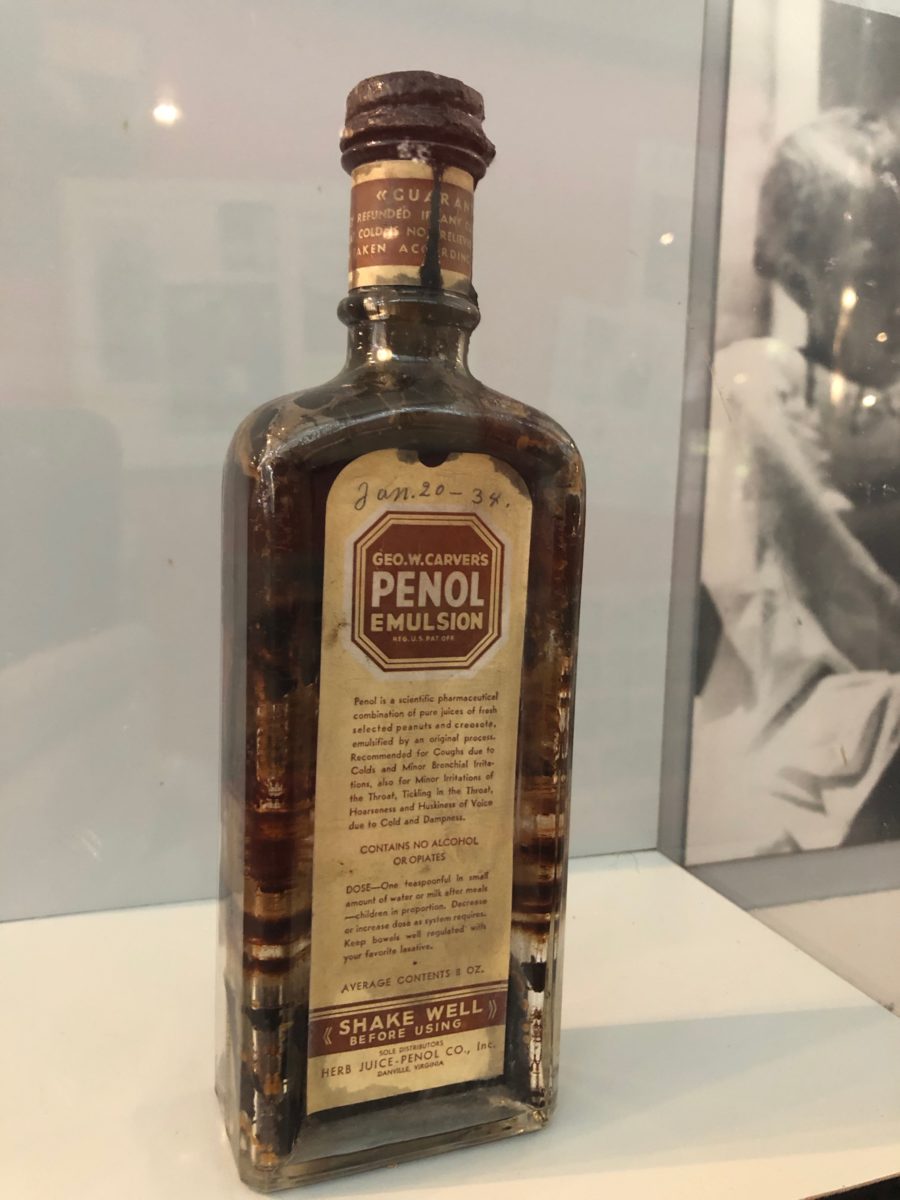

While Carver didn’t actually invent peanut butter, he popularized it and developed new products like rubbing oil, medicines, and hair cream derived from peanuts.

Carver also developed new foods from sweet potatoes, some of which caught on and others didn’t. But the goal, always, was to increase demand for crops local farmers in the South could easily grow.

Many of George Washington Carver’s accomplishments took place in the laboratory …

But Carver was a keen believer in getting outdoors and exploring nature – like when he was a child. Even into old age, he would wander for miles carrying this black leather case for collecting samples.

Carver, like his boss Booker T. Washington, also believed in practical education – “learning by doing”. Two of his students constructed this skeleton of an ox, which he kept as a learning tool.

Under Carver’s direction, Tuskegee assembled traveling wagon shows, designed to introduce local farmers to helpful scientific information.

Eventually this turned into the “Booker T. Washington Agricultural School on Wheels”.

Sadly, Booker T. Washington himself died in 1915 of Bright’s disease (a kidney ailment) at the relatively young age of 59.

Booker T. Washington is buried on the Tuskegee University campus, next to several generations of family members.

George Washington Carver, his star faculty member, lived a much longer life, though he never married or had children. He died in 1943, at the age of 79, one of his country’s most famous and honored scientists.

Carver is buried just a few yards away from Booker T, on the Tuskegee University campus. Next to his grave, when I visited, lay a jar of peanut butter.

But the legacy of these two men did not die with them. It went on in the many young people who graduated from Tuskegee and went on to do great things of their own.

The low point of that legacy was clearly the infamous syphilis experiment Tuskegee University conducted in collaboration with the US Public Health Service from 1932 to 1972.

600 African-American subjects, mainly poor local sharecroppers, were told they were receiving free medical care. Instead, the study charted the course of their intentionally untreated syphilis. In many cases, the subjects were not even informed of their condition.

One result of this infamous legacy was the creation of the National Center for Bioethics in Research and Health Care at Tuskegee University.

Another, far more positive legacy linked to Tuskegee is evident a few minutes down the road, at a small nearby airstrip: home of the famous Tuskegee Airmen.

In 1940, Republican presidential candidate Wendell Wilkie pledge to desegregate the US military, prompting President Franklin D. Roosevelt, competing for African-American votes, to authorize – for the first time – the enlistment of African-American aviators.

The Army Air Corps was adamantly opposed to this decision, and many of the white commanders assigned to the project were reluctant participants, eager to see it fail.

Nevertheless, starting in July 1941, African-American volunteers from around the country eagerly assembled at a few airfields around Tuskegee to receive their training as pilots.

When they arrived by bus at Moton Field, Hanger One, they were apprehensive about the challenges that awaited them.

The aspiring Tuskegee Airmen initially learned to fly in Vultee BT-13 trainers like this one inside Hanger One.

While waiting to fly, in this ready room, they might spend hours studying to identify enemy aircraft or ships.

Or, in the classroom next door, they might attend classes in radio operations or aerial dogfighting tactics.

Off base, the Airmen – many of them from other, more integrated parts of the US – faced the shock of Jim Crow segregation in the Deep South.

The standards were high, and it was all too easy to flunk out. Of the 13 cadets admitted to the first class of Tuskegee Airmen, only five graduated in March 1942.

But those five formed the core, and hundreds more followed. Nearly 1,000 ultimately graduated from the Tuskegee program.

About half of those trained pilots shipped overseas, where they were initially assigned to older, nearly obsolete fighter aircraft like the P-40.

But eventually, as US war production kicked into high gear, they received the high-performance P-51 Mustang, which the Tuskegee Airmen – serving in segregated units – painted with a distinctive red tail.

In the skies over Nazi-controlled Europe, the “Red Tails” earned the reluctant respect of the white bomber crews who they protected from German fighters, flying some 1,600 missions and destroying over 260 enemy aircraft.

The movie “Red Tails” (2012) portrays a dogfight between German fighters and Red Tail escorts, putting their training at Tuskegee to the test.

Tuskegee Airmen of the 332nd Fighter Group attending a mission briefing in Italy 1945.

The Tuskegee Airmen were a source of great pride for African-Americans on the home front.

But on the ground, especially at home, they continued to face discrimination. In 1945, when Tuskegee Airmen insisted on entering a whites-only officers club at Freeman Field in Indiana, 162 were arrested, three court-martialed, and one convicted.

Their mistreatment gave rise to a movement the Tuskegee Airmen called “Double-V”: Victory Abroad over Tyranny, and Victory at Home over Discrimination.

In a way, Double-V represented the dreams of Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Du Bois realized, and finally reconciled. Having demonstrated their worth to themselves and their country, a new, confident generation of African-Americans refused to be treated as 2nd class citizens

In March 2007, President George W. Bush presented the Congressional Gold Medal to around 300 surviving Tuskegee Airmen and their families.

And next year, in 2021, the US Mint will produce a quarter honoring the Tuskegee Airmen, with the motto “They Fought Two Wars” (against the Axis abroad and racism at home).

Thanks for joining me on another journey, and I wish you a peaceful and hopeful Memorial Day.

Leave a Reply