November 18, 2018

Prompted by my trip there in November 2018, I’m going to do two history posts on Ethiopia, one on its ancient history, one on its modern story (1800 to today).

I’ll begin with the ancient history … and it goes way back. Because modern humans – and before that, the ancestors of humans – almost certainly originated in Ethiopia. The famous “Lucy”, an early ancestor of modern humans (Australopithecus) that lived 3.2 million years ago, and was discovered in 1974 in Ethiopia, displayed in the national museum in Addis Ababa

The first likely historical reference to Ethiopia is ancient Egyptian records of trade expeditions to the “Land of Punt” in search of gold, ebony, ivory, incense, and wild animals, starting in c 2500 BC

Ethiopians themselves believe that the Queen of Sheba, who visited Israel’s King Solomon in the Bible (c 950 BC), came from Ethiopia (not Yemen, as others believe). Here she is meeting Solomon in a stain-glassed window in Addis Ababa’s Holy Trinity Church.

References to the Queen of Sheba are everywhere in Ethiopia. The national airline’s frequent flier miles are even called “ShebaMiles”.

The ruins of a palace outside Axum, in northern Ethiopia, is popularly called “Sheba’s Palace”, though most archaeologists now believe it is actually a nobleman’s house dating from the 6th Century AD (more on it later).

Similarly, a nearby ancient pool of water just outside Axum is called “The Queen of Sheba’s Bath”, though more likely it was used exactly as it is now – as a reservoir.

But the Queen of Sheba’s connection to Ethiopia’s history involves a lot more than local legends. Because Ethiopians believe that Sheba has a son with Solomon, named Menelik, who returned to Ethiopia carrying Israel’s greatest relic, the famed Ark of the Covenant.

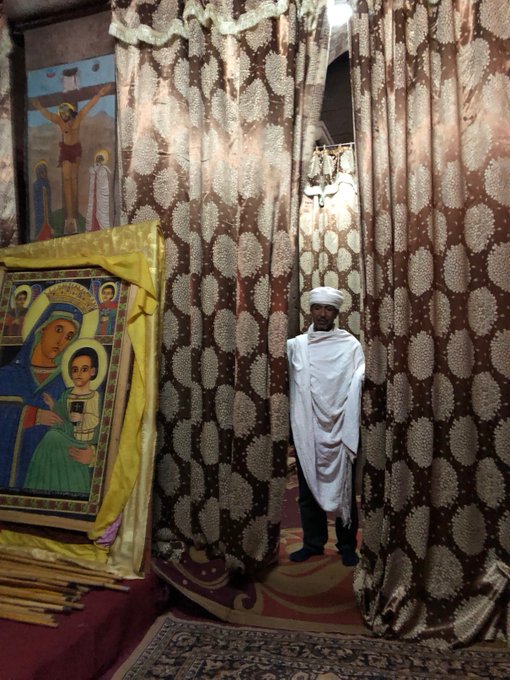

This is not some errant legend – it lies at the core of Ethiopian Orthodox Christian belief. At the heart of every Ethiopian church lies a veiled “Holy of Holies” where only the priest is allowed to enter, which contains a replica of the Ark.

Like the Israelites’ tabernacle in the desert, or the Temple in Jerusalem, every church in Ethiopia has a curtain cordoning off the Holy of Holies, where the Ark (or a representation) is kept. Many (though not all) are built in a circular form, with the Ark at its center.

As for the real Ark of the Covenant, Ethiopians beiieve it was first brought (c 400 BC) and hidden at Tana Qirqos on the banks of Lake Tana. And there IS some evidence of Jewish ritual objects at this monastery (which I did not get a chance to visit).

nd, of course, there were (until recently) Jewish communities in Ethiopia that sometimes traced their mysterious lineage back to Sheba’s son Menelik, and his journey to Ethiopia with the Ark. Wolleka, just north of Gondar, was once a village of Falashas (Ethiopian Jews). Almost all of them have moved to Israel since the 1980s airlift, but their synagogue remains.

Until the Emperor Hailie Selassie was overthrown in 1974, the various royal houses of Ethiopia nearly all traced their lineage back to Menelik and Solomon, which is why their symbol was the Lion of Judah (statue in Addis Ababa).

Meanwhile, in Axum, a kingdom was taking shape, starting as early as 400 BC. It was coincident with the Roman Empire, and traded with Rome, as well as India and China. It ranked as one of the great states of the classical world.

One of the earliest traces of the civilization is a sandstone temple at Yeha, northeast of Axum, dating from as early as the 7th Century BC. The temple is strikingly precise in both its overall geometry and its finely cut stone masonry.

Next to the temple at Yeha is an excavation through to be a palace, dating back to the same early period (7th Century BC). German archaeologists are currently working on it to learn more.

But the most emblematic of relics of Axum’s civilization are the giant granite stelae, standing in the modern city’s center, believed to be grave markers for the kingdom’s pre-Christian rulers.

The largest one, standing 33m and weighing 520 tons, collapsed sometime soon after it was built, taking out another king’s giant 360-ton dolmen tomb with it. Some (fancifully?) credit the catastrophe for triggering the kingdom’s conversation to Christianity.

It is believed that the huge granite stelae (like this unfinished one) were transported to Axum by elephants, then carved and raised on site.

Axum’s giant stelae do, in fact, stand above royal tombs, though they have long since been cleaned out by robbers.

This tomb in the Axum stelae field, dating from the 4th Century AD, was covered with a block of granite (which originally lay flat over the entrance) shaped like a door, earning it the name “The Tomb of the False Door”.

Inside of Axum’s “Tomb of the False Door” (4th Century AD) rests a mysterious sarcophagus that appears to be hollow, but has no apparent seam, so no one has been able to open it and see what’s inside.

Around 350 AD, King Ezana of Axum carved this stelae celebrating a military victory of the neighboring Kingdom of Kush (in Sudan). Written in Ge’ez (the ancient language of the Ethiopian church), Sabaean, and Greek, it serves an an Ethiopian version of the Rosetta Stone.

King Ezana’s stone (which was dug up by local farmers in their field outside Axum) also praises God for his victory, further evidence supporting records that Ezana was the first king of Axum to convert to Christianity.

Ethiopians believe that soon afterwards (400 AD) the real, original, bona fide, we’re-not-kidding Ark of the Covenant was supposedly moved from Lake Tana to Axum, where it is said to rest – to this very day – in a heavily guarded chapel next to the Church of St. Mary of Zion.

This picture is taken against the glare of the sun, but if you look close, you can see a hunched figure in a yellow shawl next to the Chapel. That is the keeper of the Ark, a monk who is the only person allowed to see it, and may never leave the enclosure for his entire life.

Every January at Timkat (Epiphany), the priests of Axum parade carrying what is supposed to be the Ark of the Covenant, but is thought to be a replica, not the real thing, which never leaves the Ark Chapel. (not my photo)

Meanwhile, Axum continued to prosper, with its coins – bearing crosses and the images of its kings – traded widely.

It was in this era, the 6th Century AD, that the mansion at Dungur, outside of Axum – commonly called Sheba’s Palace – was likely built.

It’s also in the 6th Century that the dual tombs of Kings Kaleb and Gebre Meskel were built, near Axum.

It’s also around this time that remote monasteries such as Debre Damo, north of Axum, were founded by early Ethiopian Christian saints. You can read about my climb up there here.

Like in the West, these monasteries became repositories of ancient texts and illuminated manuscripts, like this one at Yeha depicting Palm Sunday

In 570 AD, a retainer of the King of Axum, based in Yemen, nearly conquered the trading center of Mecca with a large army led by war elephants. That was the year, according to some accounts, that the Prophet Muhammed was born in that city.

The rise of Islam, in the 7th Century AD, was calamitous for the Kingdom of Axum in Ethiopia, cutting off its trade, political, and cultural links with the rest of the Christian world.

Building remote, hard-to-reach cliff-top churches in Tigray was one way Ethiopia’s Christians withstood repeated Muslim invasions over the following centuries. You can read about my climb to the rock-hewn churches of Maryam Korkor and Daniel Korkor here.

It took until the 12th Century AD to see the rise of a new (non-Solomonic) Zegwe Dynasty led by King Lalibela, who built a complex of rock-hewn churches at his capital in central Ethiopia, which took on his name.

At that time, Europe was engaged in the Crusades in the Holy Land. In 1165 AD, the Pope received a mysterious (and fake) letter purporting to be from “Prester John”, a powerful Christian king in the east who wanted to ally against the Muslims.

Initial hopes that “Prester John” might prove to be the Mongol Khan didn’t pan out. But eventually European hopes focused on the quite real Christian kingdom of Ethiopia, and were one factor that helped inspire Portuguese efforts to discover a sailing route around Africa.

In the early 1600s, the Jesuits reached the royal court in Ethiopia and actually succeeded in converting two emperors to Catholicism. But this sparked a revolt and they were ejected from the country.

Shortly afterwards, in 1636, a new dynasty, claiming descent from Solomon, established a new capital at Gondar. You can explore a separate post on the castle complex at Gondar here.

These decorations on the wall of Emperor Fasiladas’ palace banquet hall in Gondar pay tribute to the Portuguese soldiers sent to aid him in fighting the Muslims of Sudan and the Red Sea.

But by the time the Scottish adventurer James Bruce visited Gondar in the 1770s, Ethiopia had fallen into chronic civil war among rival nobles, a united empire in name only.

The story of Ethiopia from 1800 onwards continues here.

Leave a Reply