December 13, 2022

Today in Microsoft Flight Simulator, I’ll be flying the Lockheed F-104 Starfighter, a Cold War airplane with a checkered history that demonstrated that speed isn’t everything.

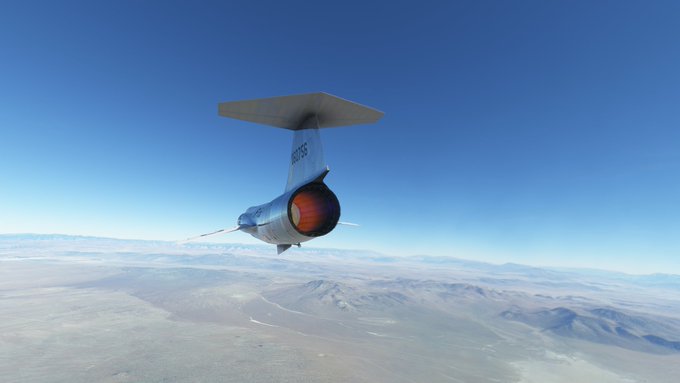

And to kick us off this morning, I’m at Edwards Air Force Base in California’s Mojave Desert, with a reincarnation of the same plane that Chuck Yeager crashed trying to set a new altitude record here in 1963.

The story of the F-104 begins in the skies over Korea, where U.S. pilots in F-86 Sabres battled MiG-15s, many of them secretly flown by Russian pilots. While the F-86 held its own, pilots reported that they wanted a jet fighter that could fly faster and higher than the MiG.

The challenge was taken up by Kelly Johnson, the famous head of Lockheed’s Skunkworks, who designed many of the company’s most groundbreaking planes, including the L-10 Electra and P-38 Lighting, and later the U-2 and SR-71 Blackbird spy planes.

I’ve already done a post on the L-10 Electra airliner, introducing Kelly Johnson’s early career, which you can check out here.

And I’ve done another post on the P-38 Lightning, whose design emphasis on speed and altitude shares a lot in common with the later F-104.

The F-104 Starfighter would be propelled by a single General Electric J79 jet engine, an absolute monster that produced over 14,000 lbs of thrust.

The main wings of the F-104 were stubby, extremely thin, and tilted downwards (anhedral) as a counter to the T-tail behind. The forward edges of the wings were so sharp they created a safety hazard to ground crew – accidentally bang into them, and they could cut like a knife.

When flying at high angles of attack, the wings could potentially mask the T-tail from the airflow, rendering the elevators useless and making it impossible to pitch down to recover – something I learned I really had to watch out for.

The cockpit is all analog gauges. The most important are the artificial horizon to the middle right, the altimeter to the middle left, and the airspeed indicator just above it. The engine gauges to the far right are very important too, because this thing is easy to overheat.

The throttle to the left is pretty simple. Just next to it is the level for flaps. There’s only one stage of flaps, about 10 degrees, for takeoff and landing.

The first F-104 prototype took to the skies in March 1954, here at Edwards Air Force Base.

And quickly earned its reputation as “a missile with a man on it”.

In the first few months, the F-104 broke numerous altitude and speed records, becoming the first jet fighter to exceed Mach 2.

But it also soon revealed a number of flaws and limitations that would plague it throughout its career.

First, while it was extremely fast, it had a very wide turning radius, which made it unsuitable for close-in dogfighting. This became evident to me when I made a 180-degree turn to land and kept way overshooting the runway.

Second, when you have the engine on full throttle, it’s very easy for the compressor to stall and cause the engine to flame out. This happened to me several times, throwing me violently forward in the cockpit. I was high enough, so I could restart.

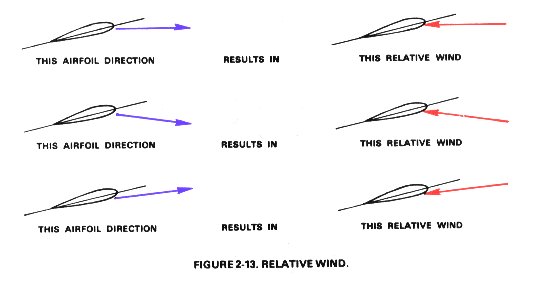

For #3, I need to briefly explain about angle of attack. It’s not pitch up or down, exactly, it’s the angle your wing meets the air. The higher that angle, the more lift – but beyond a certain point, the wing will stall and cease providing any lift at all.

The angle of attack indicator it the dial to the far right. It’s on 3 here. When it goes to 5 or more, the stick starts shaking to warn me. And if it goes into the red, the stick will automatically push forward, causing the plane to lurch nose down.

At first, I found it challenge to manage the angle of attack at speeds below 200 knots. In fact, that’s why the F-104 was known for having to land at a relatively fast speed.

In fact, this was the result of my first attempt to land the F-104. Needless to say, it was a closed casket funeral.

For all these reasons, the F-104 was one of the first jet fighters to feature an ejection seat. Pull that cord down between my legs and away we go.

The problem was, the first explosive charges for the F-104’s ejection seat couldn’t propel the pilot above the oncoming T-tail. So the pilot was ejected DOWNWARDS out the bottom of the fuselage. Oh yeah.

F-104 pilots wore these spurs, which clipped into wires that, when they ejected, pulled their legs in from the rudder pedals so they wouldn’t get ripped off. The pilots loved these because when they walked around it made them look and feel like cowboys.

Ejecting downward at high altitudes wasn’t a problem, but it became deadly at low altitudes on final approach. The ejection would slam you right into the ground before your chute could open.

Eventually this was changed and new explosive charges were rigged to blow off the canopy and eject the pilot skyward – which has remained the practice ever since.

The F-104 is probably most familiar from the scene in “The Right Stuff” where Chuck Yeager tries to fly one to the edge of space and ends up losing control and ejecting just before it crashes. You can watch it below:

This was a real event, and the plane he flew (NF-756) was actually an experimental version of the F-104 with a rocket (not depicted here) attached to the tail, providing an additional boost to reach maximum altitude.

Yeager actually began his run level at 40,000 feet to build up speed to Mach 2.2 before starting his climb.

Then he nosed up 45 degrees or more and shot for the sky. At 78,000 feet he shut off the main engine and let the tail rocket propel him higher.

In the movie, it makes it look like the problem was that his engine failed. In fact, that wasn’t the issue. The problem was that around 107,000 feet, for some reason the elevators became locked and he couldn’t nose down as he lost speed.

Unable to regain speed by nosing back down, the plane went into a flat spin and Yeager ultimately had to eject. The seat hit him and caused the rubber in his helmet to catch fire, burning his face and one of his fingers very badly. But he survived.

I don’t have an extra tail rocket, and was still learning the ropes with the finicky engine, so the highest I was able to get the F-104 to was about 50,000 feet.

The view there was pretty wild, though.

The fastest I could get the F-104, on my first flight, was Mach 1.4. Though I think with a little practice I could probably figure out how to get up past Mach 2.

Time to come back down to earth and try to land right this time.

Barreling in at 200 knots is a little unnerving (a Cessna lands at about 60 knots, a 737 at about 130).

Once you do touch down, the F-104 has a parachute you can deploy to help slow you down in time – before you run out of runway.

Later versions of the F-104 also had a tailhook that could catch wires on certain airfields to come to a halt. Either way, even in the sim you definitely feel yourself behind slammed forward as you decelerate.

The F-104 was initially deployed as a high-speed interceptor and played a key deterrent role in the 1958 Taiwan Straits Crisis, the 1961 Berlin Wall Crisis, and the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis.

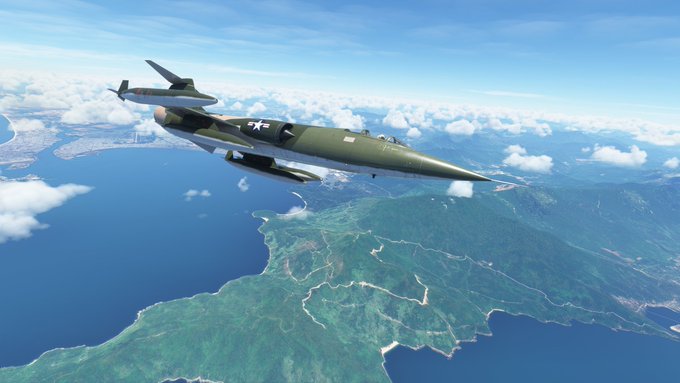

But the limitations of the F-104 in an actual combat role became evident during the Vietnam War – which is why I’m here at the giant US airbase at Da Nang (now a civilian airport).

One big drawback was limited range. The F-104 guzzled fuel, and would quickly run out of gas if it didn’t carry an array of extra fuel tanks on its wings to supplement.

You’ll notice that as it sits on the runway, the F-104 constantly snorts steam and smoke from its vents like some kind of dragon.

The F-104 was designed to intercept and shoot down other jet fighters. But there were few enemy fighters that posed a direct threat in the skies over Vietnam.

As a result, in almost 3,000 sorties during the Vietnam War, the F-104 scored zero direct air-to-air kills, though several were lost due to accidents and enemy fire (one was reported shot down by a Chinese fighter jet after straying into Chinese airspace).

It can be argued that the F-104 Starfighter did perform its job well: by patrolling the skies, it deterred North Vietnamese fighter jets which largely avoided it, ensuring the safety of other US aircraft involved in providing closer air support to troops fighting on the ground.

Nevertheless, the F-104 was soon phased out of the U.S. Air Force, replaced by other jets like the F-4 Phantom which, while not as fast, could serve in a more versatile range of roles, from dogfighting to bombing to landing on an aircraft carrier.

That was hardly the end of the F-104, however. Just as its life with the US Air Force was ending, it was gaining popularity in export markets, including the US-recognized Republic of China on Taiwan.

On January 13, 1967, four ROCAF Starfighters engaged a formation of PLAAF MiG-19s here, over the island of Kinmen (Quemoy) just off the coast of mainland China.

One F-104 did not return to base, and was presumably shot down. But two Taiwanese pilots shot down a MiG-19 each.

Kelly Johnson said this aerial battle illustrated both the strengths and weaknesses of the fighter he designed. It had the advantage in speed and altitude, but could not turn with the MiGs.

This particular plane, #4344, survived and is still on display at the ROC Air Force Museum in Kaohsiung, Taiwan.

Let’s see if I’ve learned anything and can land it at the airport below me on Kinmen, which is still held by Taiwan, just a few miles offshore the large Chinese coastal city of Xiamen.

Spotting the runway off my left side on downwind.

A very wide, lumbering turn, and now barreling in at a bit over 200 knots.

Clunk. Welcome to Kinmen. You can see the force of the deceleration pushing the pilot’s head forward.

Several other countries also adopted the F-104 in the mid-1960s. One of the most important was Canada, which acquired a license from Lockheed to produce them domestically as the CF-104.

This CF-104 being refueled belongs to the 3rd Fighter Wing once based here at Zweibrucken, in southwest Germany.

At the time, Canada actually had the 4th largest air force in the world, with four bases in Western Europe, two in France and two (including Zweibrucken) in West Germany.

The Canadian CF-104s at all four bases replaced F-86 Sabres, and took on two special missions. The first was aerial reconnaissance.

The second mission – a unique one – was nuclear strike.

The Canadian CF-104s carried a single, compact nuclear bomb under its fuselage, like a drop-tank, which unfortunately I’m not able to depict here.

In wartime, the job of the Canadian CF-104s was to take off and fly straight to targets inside the Soviet Union, and drop their nuclear load.

The thing is, even if with wingtip fuel tanks, the CF-104s didn’t have the range to fly to Russia and back. The pilot would be expected to bail out somewhere near the target and hide (!) until the war ended.

That’s a pretty rough assignment. I’m glad I’m not this guy – and that this guy never actually had to perform his mission.

Canada operated the CF-104 for 25 years, from 1962 to 1987, when it was replaced by the F-18 Hornet.

Like many other countries that flew the Starfighter, Canada had a very high accident rate – 110 major accidents and 37 fatalities – which gained it the nickname “The Widowmaker”.

But the country that ordered the largest number of export F-104s, and had the highest accident rate, was West Germany.

The Starfighter we’re looking at here is a little different: it’s a two-seat TF-104, used as a trainer. When countries deployed the F-104, they typically bought a few TF-104s as part of the package.

This TF-104 belongs to JaboG 34, a fighter-bomber squadron once based here at Memmingerberg, in Bavaria, now a civilian airport.

Starting in 1960, the West Germans bought 915 Starfighters, 35% of all F-104s ever produced, as part of a plan to quickly ramp up their contribution to NATO’s fighting force.

Of these 915 planes, 292 (almost 1/3) were destroyed in accidents. 116 pilots were killed. At one point, there was an accident happening almost every week.

This was the worst safety record of any country operating the F-104. Why was it so bad? There are several reasons that probably contributed.

First, many pilots in the new Luftwaffe were inexperienced, with only a few older veterans signing on who had flown in World War II.

Many of the problems with the F-104 persisted: engines flaming out, stalling at high speeds, T-tail elevators becoming ineffective, etc. Even at its best, the Starfighter was considered a very unforgiving aircraft. In the hands of an inexperience pilot, this could be deadly.

Second, to save money, the Germans made the F-104 their one and only type of airplane. Originally designed as a high-altitude interceptor, they had it play a wide variety of roles, including low-altitude combat support bomber.

This low-altitude bombing role led to a number of accidents where pilots couldn’t pull up fast enough from a dive and crashed.

Third, many German pilots received their F-104 training in the American Southwest, where the weather was clear and ideal. When they came back to Europe, they found themselves operating in poor weather conditions close to the ground. Many accidents were weather-related.

Finally, that ejector seat. Many German pilots trained on F-104s with a downward ejecting seat. They learned to adapt at low altitude by turning the plane upside down before ejecting, so they’d be propelled away from the ground.

By the time the Germans got their planes, though, many had been changed to UPWARD ejecting seats. But by force of habit, some pilots would still turn upside down before ejecting at low altitude and … well, you know.

If this ongoing bloodbath wasn’t enough, though, Germany’s purchases of the F-104 became the center of a major bribery scandal.

In the 1970s, several German politicians, including the Defense Minister, were accused of taking multi-million dollar bribes from Lockheed to choose the F-104 over its rivals. Similar charges were made against Lockheed in other countries, involving the F-104 and other aircraft.

Coming in for an appropriately wild landing back at Memmingerberg, Germany.

For all its flaws, the West German Luftwaffe continued to rely on the F-104 as its primary warbird until it was replaced by the Panavia Tornado in the 1980s.

British pilot Eric Brown said the F-104 was an airplane that “has to be flown every inch of the way.” The U.S. required pilots to have 1,500 flight hours before getting into the F-104. German pilots typically had 400. It showed.

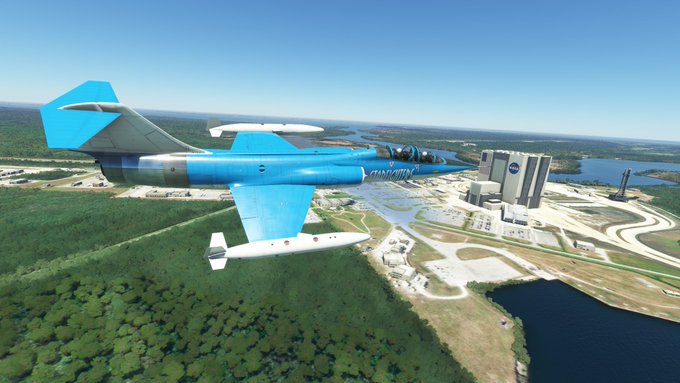

Now if all of this makes you want to climb into a F-104 and try it out, you may be in luck. An outfit called Starfighters, Inc. offers a 2-day program of flight training in one, out of Kennedy Space Center, for $29,900.

Their small fleet of former Canadian TF-104s operate out of a hangar at the Space Shuttle landing facility.

If you have that kind of money lying around, all you need is a private pilot license, a medical certificate, and be within certain maximum height and weight limits – and be able to pass a security check to get on site.

For the fee you’re paying, I certainly hope they let you go Mach 2.

I don’t have that kind of change, but at least in the sim I can fly over Kennedy Space Center and wave hello to Elon Musk.

So yeah, your dreams can come true, it can happen to you. If money is no object.

In the meantime, the rest of us will have to make due with Microsoft Flight Simulator.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this post on the F-104 Starfighter and its interesting history. And maybe at least one of you with go to Florida and fly one. Good luck!

Leave a Reply