January 3, 2023

Today in Microsoft Flight Simulator, I’ll be flying the Grumman F6F Hellcat, the most successful carrier-based Allied fighter of World War II.

And to tell that story, I’m aboard the USS Essex (CV-9) just off the eastern coast of the island of Luzon in the Philippines, on the morning of October 24, 1944.

Just a few days before, on October 20, General Douglas MacArthur waded ashore on the island of Leyte to the south, fulfilling his pledge to “return” to the Philippines and liberate it from Japanese occupation.

That summer, the US Pacific carrier fleet had met the remaining Japanese carriers off the Marianas Islands. In the “Great Marianas Turkey Shoot”, US pilots had wiped out their Japanese counterparts in the air.

With its carriers denuded of aircraft, Japan now looked to its surface fleet based in Singapore, including its two mega-battleships the Yamato and Musashi, to sail to the Philippines and obliterate the American landing force on the beaches.

Off the east coast of the Philippines, Task Force 38, under the command of Admiral Halsey, consisted of nearly a dozen full-size fleet carriers plus a score more smaller escort carriers, assigned to provide air cover for the landing.

On the morning of October 24, planes aboard the USS Essex were fueling to take part in a strike on the advancing Japanese battleships, which had been detected by American submarines steaming towards the landing beaches through the archipelago south of Luzon.

In the starting days of World War II, the US Navy’s main carrier-based fighter had been the Grumman F4F Wildcat.

The creator of the Wildcat – and later the Hellcat – was Leroy Grumman, who headed a relatively modest aircraft company of the same name based on Long Island, NY.

Grumman began his aviation career as a US naval pilot during World War I. Though he failed his medical exam due to flat feet, a clerical error allowed him to get through flight training.

Grumman was assigned by the Navy as a test pilot to help assess aircraft produced by Grover Leoning, a German immigrant who graduated from Columbia University with the world’s first degree in Aeronautical Engineering and then learned his craft working for Orville Wright.

Grumman became Leoning’s protege and worked for him as a designer and test pilot after the war, on float planes for the US Navy. When Leoning’s company was acquired in 1929, Grumman formed his own, retaining his focus on naval aviation.

By the time the U.S. Navy adopted the Grumman F3F biplane (which I did a post on here) as its main carrier-based fighter, in the years immediate prior to World War II, Grumman was well established as a go-to supplier of combat aircraft to the Navy.

The F4F Wildcat (the F3F’s successor) came into service a year before Pearl Harbor. It was not as maneuverable as the Zero, and the cockpit had poorer visibility. But it could out-dive the Zero, and could also take a lot more punishment than its fragile Japanese rival.

Overall, the Wildcat and the Zero were fairly evenly matched, each with its own strengths and weaknesses. You might want to check out the separate post I did on the Zero here:

As the early war in the Pacific unfolded, Grumman sent its designers to the field to talk with pilots flying the F4F Wildcat against the Zero in combat. They asked veteran F4F aces like “Butch” O’Hare (pictured below) what kind of improvements they needed to defeat the Zero.

The result was the F6F Hellcat. Superficially, the Hellcat looks a lot like the F4F Wildcat, and at first glance can be hard to tell apart. But there are a few telltale differences.

First of all, when lined up next to each other, it’s clear that the Hellcat is longer, larger, and taller than its predecessor, earning it the nickname “the Wildcat’s big brother”.

The most obvious difference, once you know where to look, is the landing gear. The F4F’s landing gear could be retracted into the fuselage, but had to be cranked by hand – not the easiest task just before or after landing on aircraft carrier.

The Hellcat’s gear, in contrast, could be raised and lowered automatically, using hydraulics. Because they retracted into wing wells, the wheels were wider apart, which made them more stable to land on without tipping over.

One of the most distinctive features of both Grumman fighters were their foldable wings, which saved deck and hangar space, making it possible for a ship to carry 1/3 more airplanes. (In contrast, Japanese Zeros did not have folding wings).

When lowered for flight, the wings were locked into place with a big hydraulic metal bolt – which I think is the white circle you can see next to the red hook.

The Hellcat’s flaps have only one setting, up or down. The outer flap section is canvas-covered, the inner one is metal so the pilot can step on it to climb into the cockpit.

A major innovation on the Hellcat is spring-loaded flaps. If lowered at too high a speed, the air current would push them back up again. That meant pilots didn’t have to get distracted worrying about exceeding the maximum flap speed (170 knots), either when dogfighting or coming in to land.

Of course, the Hellcat has a tailhook for catching a wire on the carrier deck, which allowed it to come to a quick stop. The rear wheel is made of solid rubber, to put up with the pounding and abuse typical aboard cramped aircraft carrier decks.

Both the Wildcat and Hellcat were built like a stubby beer barrel – no competing with the sleek elegance of a Spitfire or Mustang here.

The F6F replaced the F4F’s single Pratt & Whitney Twin Wasp 1200hp engine with a Double Wasp capable of producing 2000hp. For perspective, that’s more than 10x the horsepower of a Cessna 172.

Though they used the same powerful engine, the Hellcat’s nose was much shorter than the rival F4U Corsair’s, and angled slightly downwards, making it much easier to see during carrier landings.

I did a separate post on flying the gull-winged Corsair, where I talk about the same issue and why the otherwise fast and powerful F4U got relegated to the Marines, who were mostly based on land.

Oh, and before I forget: the main armament of the F6F Hellcat: three 50-cal Browning machine guns on each wing (vs. two per wing on the Wildcat). I’ll talk more about combat tactics in the Hellcat when we’re in the air.

And we’ll be in the air soon, because this morning we’re joining David McCampbell, Commander of Fighter Squadron 15 (VF-15) aboard the USS Essex, as he refuels for a strike mission on the Japanese battleships.

To the right are our lights and radio switches, as well as our engine gauges.

To the left, as usual in a WW2 fighter cockpit, the throttle, mixture, and prop controls, trim wheels, flaps, landing gear, etc.

We have a neat little slide out map table for navigation, below our main instruments. And a pin-up photo of Betty Grable for inspiration.

While Campbell is fueling, the word comes in over the flight deck loudspeaker: a wave of land-based Japanese planes is inbound from the Philippines to attack the American carrier fleet. The planned mission is scrubbed – all fighters must get into the air to meet them.

Campbell disengages the fueling, with his tanks only half full, and immediately gets ready for takeoff despite the crowded deck.

At this point in the war, some carriers did have catapults, but many takeoffs took place without them. Flaps down. Brakes on. Rev to no more than 2000 RPM – any faster and the Hellcat will tip over. Release brakes and put in full throttle.

A slight lurch as we leave the flight deck, then steady climb. Gear up. Flaps up. And we’re off to meet the incoming Japanese planes.

By the way, the flight control officer that just launched us from the USS Essex was Lieutenant John Connally, Jr., the future Secretary of the Navy and Governor of Texas who, not quite 20 years later, would be wounded sitting in front of JFK in Dallas.

As we level off and search for the Japanese planes, I bring the throttle back to 44 inches manifold pressure and reduce the prop to 5500 RPM. These are the Hellcat’s cruise settings, and if I go higher in altitude (up to a service ceiling of 37,300 feet), I can engage the supercharger to keep the manifold pressure up.

While the Wildcat was roughly matched to the Zero, its strengths making up for its weaknesses, the Hellcat completely outclasses its opponent, which was designed to its limits and has not been improved since the war began.

Campbell has already shot down 21 enemy planes, many of them during the Great Marianas Turkey Shoot that summer.

This morning, he and his wingman Roy Rushing get separated from the rest of his squadron. They’re on their own, looking for enemy planes.

Suddenly, in front of them they see a host of nearly 60 Japanese planes, a motley mix of fighters and bombers thrown at the US fleet from land bases in Luzon.

Without a second thought, outnumbered 30 to one, the two Hellcats engage. I put my throttle full to nearly 48 inches manifold pressure, put the prop to max 7000 RPM, for full combat power.

The Hellcat still can’t out-turn the Zero in close combat, but it doesn’t need to. It uses its superior power to hit fast and hard from on high. Its superior armor allows it to shrug off stray enemy bullets as it plows through the enemy’s ranks.

Speed was another crucial factor. The F6F had a maximum speed of 391 mph, compared to 331 mph for both the F4F and Zero.

From the day it was introduced in 1943 to war’s end, the Hellcat racked up a kill ratio of 19:1 (19 Japanese planes shot down for every one Hellcat lost). Against the Zero it was 13:1.

This ratio was partly the result of the Hellcat’s innate superiority, but also the result of severe losses among trained Japanese pilots, and the inexperience of the pilots who replaced them.

On this morning, October 24, 1944, Campbell shot down 9 enemy planes, seven Zeros and two Oscars, setting a US single-mission aerial combat record. His wingman shot down another six, for a total of 15.

Campbell soon realized, though, that having taken off on only half-filled tanks, he was quickly running out of fuel, and needed to land as soon as possible.

The flight deck of the Essex was full, so he was waved off and had to land on the escort carrier USS Langley (CVL-27) instead.

I only have the USS Essex, so I’ll have to make due.

I don’t know if it’s an issue with the flight model, but I found that I had to land much faster than just above the stall speed of 60 mph, otherwise I’d have to pitch up to high I couldn’t see over my nose. Or maybe I just need more practice.

When Campbell landed on the Langley, he discovered that he had just two bullets left in his magazines, and the engine gave out immediately for lack of fuel, even before they could push him off the landing wires. The wire here kind of jerked me around sideways when it caught.

Campbell received the Medal of Honor for his actions that day. He downed a total of 34 enemy planes by the end of the war, making him the U.S. Navy’s all-time leading ace. He survived the war and lived until 1996.

But the battle that day was far from over. In the air above the same carrier task force, the Hellcats of VF-27, each painted with a distinctive “cat’s mouth” nose, were on the hunt.

VF-27 was based on the light carrier USS Princeton (CVL-23). #7 (aka “Paper Doll”) was normally flown by Ensign Robert Burnell, who came up with the idea to paint the unconventional “cat’s mouth” on each of the squadron’s planes.

On this day, however, “Paper Doll” (#7) was being flown by Lt. Carl Brown Jr. of Texarkana, Texas.

#17 was flown by LT Richard Stambook, of Kansas City, already a double-ace who had earned the Silver Star during the Marianas Turkey Shoot.

That morning, the squadron engaged another large group of 80 Japanese planes heading from Luzon to attack the American carriers.

Between them, the Cat’s Mouth Hellcats shot down 36 of them. Brown, flying “Paper Doll”, shot down five of those, making him another “ace in a day” and earning him the Navy Cross.

Meanwhile, though, some of the Japanese planes made it through. Shortly before 10:00am, a single bomb hit the flight deck of the USS Princeton, setting it on fire.

The cruiser USS Birmingham (CL-62) came alongside to fight the fire and render assistance.

Then at 3:24pm, a huge explosion – probably the detonation of stored bombs and torpedoes – ripped through the USS Princeton, doing severe damage to the USS Birmingham alongside, killing 233 and injuring 426 on the latter.

Stambook and most of VF-27 were on the USS Princeton refueling when the attack came. When the secondary explosion occurred, he and others jumped overboard and were rescued. Their planes were obviously lost.

At 5:49pm, a third even larger explosion blew apart the front section of the USS Princeton and it sank moments later. Surprisingly, due to daring rescue efforts, only 108 aboard were lost, while 1,361 were rescued.

Meanwhile, Carl Brown and a handful of other VF-27 pilots were able to land on the USS Essex, where apparently their un-regulation Cat’s Mouths drew some raised eyebrows.

Those eyebrows weren’t raised for long, however, as the squadron’s Hellcats had to be pushed off the USS Essex’s over-crowded flight deck to make room for ongoing operations.

When VF-27 later received a new home and new Hellcats aboard the USS Independence (CVL-22), it was without their signature Cat’s Mouths. Overall, though, the squadron claimed 136 enemy aircraft shot down before the Princeton was sunk, plus one more before the war’s end.

Not all the Navy’s Hellcats played defense that day. Recall that McCampbell was fueling up for a strike on Japan’s super-battleships when the word came that Japanese planes were inbound.

A third carrier in the same task group, the USS Lexington (CV-16) got off a strike force that included F6F’s armed with 4,000 lbs of bombs. We join them now, flying across the southern isthmus of Luzon to attack their Japanese targets.

This particular Hellcat, #99 (aka “Hangar Lilly”), was flown by the commander of Lexington’s VF-19 fighter squadron, Theodore “Hugh” Winters of Society Hill, South Carolina.

Winters had already flown in the Allied invasion of North Africa, before switching to the Pacific in 1943. He shot down several Japanese planes over the Philippines the month before, in preparation for the U.S. landings on Leyte.

Time to jettison our drop tank and begin our attack run on the Japanese fleet trying to sneak its way through the Sibuyan Sea.

Winters led his squadron of Hellcats, along with dive-bombers and torpedo-bombers from the Lexington, through a rain of enemy anti-aircraft fire to hit the Japanese fleet, including the battleship Musashi.

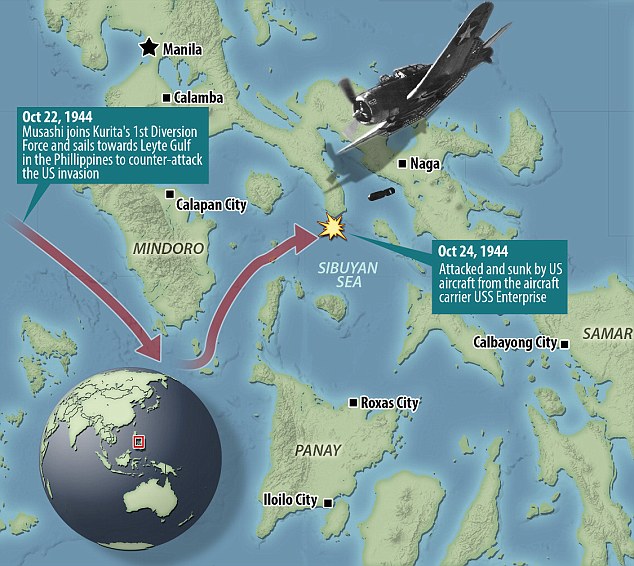

Two Japanese battleships and four cruisers were severely damaged in the attack, including the Musashi, which was sunk.

Here is the location where the Musashi was sent to the bottom. (The map says aircraft from the USS Enterprise, but Winters and others from the USS Lexington also participated).

Winters continued flying through withering AA fire to gather critical intelligence on the damage done to the Japanese fleet, for which has was awarded the Navy Cross.

U.S. commanders wrongly assumed that the sinking of the Musashi had stopped the Japanese fleet. So Admiral Halsey sent his carriers (including the USS Lexington) in pursuit of a group of Japanese carriers to the northeast.

That next day, October 25, Winters again helped lead the attack, contributing to the sinking of one fleet carrier and two light carriers – for which he received his second Navy Cross in two days.

But the Japanese carriers were meant as a diversion. They hardly had any planes, and posed no real threat. Halsey had been fooled into a leaving a critical strait unguarded.

The rest of the Battle of Leyte Gulf unfolded farther to the south. The U.S. Navy emerged victorious, and the landing beaches were protected, but Halsey came in for fierce criticism.

The U.S. was not the only Allied navy to rely on the F6F Hellcat. Britain’s Royal Navy received 1,263 F6Fs under Lend-Lease. Initially redubbing it the “Gannet”, the British quickly reverted to the popular name “Hellcat” for simplicity.

The Pacific was a carrier-based naval war. In the Atlantic, in contrast, the Hellcat had fewer opportunities to go head-to-head with the German Luftwaffe. We’re joining the HMS Emperor in the North Sea for one such episode.

Operation Hoops, in May 1944, was a carrier-based operation launched from Scapa Flow to harass German coastal shipping off the coast of occupied Norway.

This particular aircraft was flown by Lt. Blythe “Jock” Ritchie of No. 800 Squadron.

Just the previous month, the squadron had escorted a bombing raid that had seriously damaged the German battleship Tirpitz (sister ship of the Bismarck) as it hid in a Norwegian fjord.

Now they were back, hitting oil tanks at Kjen and a fish oil factory at Fosnavaag.

Suddenly the Hellcats came under attack from a group of German fighters. Ritchie succeeded in shooting down a Fw 190 – his fifth kill, and his first in a Hellcat.

His mates shot down two Me 109s, at a loss of one Hellcat. But the defeat of the formidable Fw 190, in a head-to-head dogfight, showed that the F6F could compete with the best the Germans could throw at it.

Many British pilots preferred the F6F Hellcat to the sleeker Seafire (a version of the Spitfire adapted for carrier operations), in large part because it was easier to land safely.

The wider undercarriage and slower approach speed of the Hellcat made it much easier to land on a carrier deck without tipping over.

A few months later, in August 1944, the HMS Emperor and No. 800 Squadron’s Hellcats had relocated to the Mediterranean coast of France to support the Allied invasion there, Operation Dragoon.

This particular F6F, painted with “invasion stripes” for the operation, was flown by a Dutch pilot, Charlie Poublon.

It was forced to ditch off the Spanish coast after being hit by flak.

British F6F Hellcats also flew in the Indo-Pacific Theater, like this one from No.1839 Squadron from the HMS Indomitable, patrolling over the coastal jungles of Sumatra in early 1945.

Overall, British Hellcats claimed a total of 52 enemy aircraft kills during 18 aerial combats from May 1944 to July 1945. After the war, they were rapidly phased out in favor of British aircraft.

Meanwhile, Grumman kept churning out F6F Hellcats for the U.S. Navy by the thousands in their factory in Bethpage, Long Island.

In May 1945, the 10,000th Hellcat was delivered to Bombing Fighting Squadron VBF-87 on the USS Ticonderoga (CV-14).

It would be flown by the squadron’s commander, Porter “Maxie” Maxwell of Charleston, West Virginia, a graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy Class of 1936.

VBF-87 was created to conduct air support and bombing operations aimed at Japan’s home islands, in preparation for an expected invasion landing.

Including attacks on the massive naval yards here at Kure, where the super-battleships Yamato and Musashi had been built.

But this was no victory lap. On July 24, Maxwell and his squadron were flying near Kure, seeking out air bases where Japanese kamikaze aircraft might be hiding …

When suddenly Maxwell’s wingman saw his tail disintegrate, most likely from ground fire. Maxwell tried to bail out at the last moment, but his parachute didn’t open and he hit the water next to his plane. He was 31 years old. Less than a month later, the war was over.

A total of 12,275 F6F Hellcats were produced in just two years, during the war. They flew 66,530 combat sorties for the U.S. Navy and Marines, and claimed 5,163 kills – over half of all U.S. Navy/Marines air victories in the Pacific – with only 270 Hellcats lost in air-to-air combat, 553 lost to ground fire.

The F6F produced the most aces (305) of any aircraft in the U.S. inventory. The top ace, David McCampbell (who we met at the start of this post) called the Hellcat “an outstanding fighter plane. It performed well, was easy to fly, and was a stable gun platform, but what I really remember most was that it was rugged and easy to maintain.”

After the war, the Hellcat’s job was not quite over. In the summer of 1946, the U.S. tested two atomic bombs on an armada of surplus vessels at the Pacific atoll of Bikini, in the Marshall Islands.

To help evaluate the tests, the U.S. military assembled a small fleet of pilotless drones, consisting of F6F Hellcats and B-17 bombers. The Hellcats drones took off from this airfield on Roi Island off Kwajalein.

Within hours of the detonations, the F6F drones were flown by remote control over the test site, collecting information on radiation, air pressure, and physical damage.

The Navy continued to fly Hellcats drones for research well into the 1950s. It also experimented with using unpiloted Hellcat drones as “suicide” bombs against hardened targets in the Korean War. That effort was largely unsuccessful.

The drone program gave rise to at least one crazy incident in 1956 where a Hellcat drone went rogue and circled over the heavily-populated Los Angeles area for several hours, while jet fighters scrambled to try to shoot it down safely.

The jets fired 208 missiles at the Hellcat, and all missed. Eventually it ran out of fuel and crashed, lighting a brushfire. You can read about the so-called “Battle of Palmdale” here:

A bit more inspiring post-war role for the F6F Hellcat came about in early 1946, when it was chosen as the aircraft for a new U.S. Navy Flight Demonstration Squadron.

Their first aerobatics display took place here, at Jacksonville, Florida, to celebrate the opening of the city’s new municipal airport.

Decked out in navy blue with gold letters, the team of Hellcats soon became known as the “Blue Angels”.

Needless to say, the U.S. Navy Blue Angels continue to perform (now flying FA-18 jet fighters) to this day.

Most wartime F6Fs, however, were sold for scrap. A handful continued to serve in combat, like this French Hellcat based at Tan Son Nhat outside of Saigon (in French Indochina) in 1952, fighting the Viet Minh.

The last country to fly the Hellcat was the Uruguayan Navy, which had them up until the 1960s. Today, worldwide, out of over 12,000 produced, there are only five F6Fs still capable of flying.

I hoped you enjoyed this brief glimpse into the story of the Grumman F6F Hellcat, the most successful carrier-based fighter plane in World War 2.

Leave a Reply