December 14, 2022

Today in Microsoft Flight Simulator I’m going to be flying the Fokker F.VII, one of the world’s first civilian airliners that, in the hands of aviators like Richard Byrd and Charles Kingsford Smith, also blazed new paths to uncharted reaches of the globe.

Anthony Fokker was Dutch, born in the colonial East Indies. In 1910, at age 20, he moved to Germany to pursue his interest in aviation. He soon founded his own airplane company there.

During World War I, Fokker’s company designed a number of successful and famous fighter planes for the Germans. Fokker himself was an accomplished pilot.

I did a previous thread on flying the Fokker Dr.I triplane, which you can check out here:

After losing WWI, Germany had to surrender all its warplanes and aircraft factories, including Fokker’s factory, under the Treaty of Versailles. Fokker, however, was able to bribe railway and border officials to smuggle some of his equipment back to his native Netherlands.

That equipment allowed him to reestablish his company in Holland and design the Fokker F.VII, a single-engine transport for the fledgling post-war civilian market. I have one of those models here, in KLM colors, at Amsterdam’s Schiphol Airport.

The F.VII’s fuselage was fabric stretched over a steel-tube frame. Its wings were plywood-skinned.

The original, single-engine version of the F.VII was powered by a variety of different models of radial engines, which ranged from 360 to 480 horsepower.

Inside there was room for 8 passengers, as well as a bathroom (the door to my right here).

The cabin was connected to the 2-man cockpit by a little door under the fuel tank and starter switches.

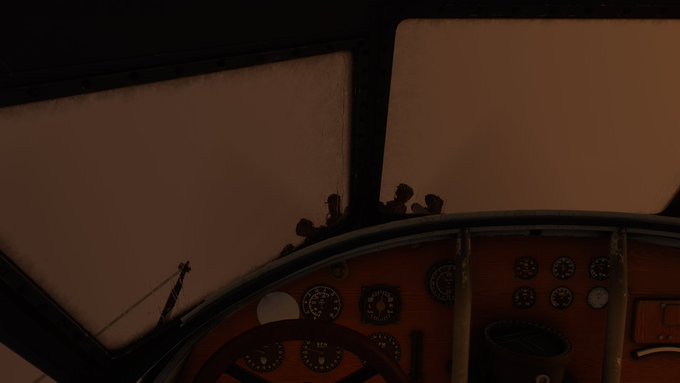

On the instrument panel, from left to right: oil pressure and temperature, altitude, another oil temperature gauge, air speed indicator (with a turn indicator below it), clock, and RPM tachometer.

What’s most interesting about the cockpit is you can see all the pullies connecting the controls to the flight surfaces outside. Turn or push the yoke and they quite clearly move. Fly by wire indeed.

The compass is basically a bowl with a magnet floating in it.

With a single engine, even a fairly powerful one, the Fokker F.VII didn’t exactly spring off the ground. It lumbers into the air and climbs very gradually.

Nevertheless, in the early 1920s, the F.VII became a successful early passenger transport for early airlines like Dutch KLM and Belgian Sabena. Here I am flying over the historic center of Amsterdam.

In 1924, the F.VII even introduced flights from Amsterdam to the East Indies. Needless to say, it wasn’t non-stop, and could take many days.

I should mention that the designer of the initial F.VII was Walter Rethel. He was later hired by Willy Messerschmidt and went on to design the famous Bf109 fighter, the main German fighter at the start of WW2.

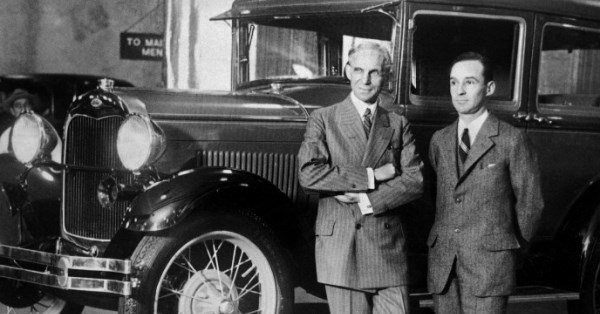

In 1925, automakers Henry Ford and his son Edsel began the Ford Reliability Tour, a challenge for aircraft to successfully complete a 1900-mile course across the American Midwest with stops in 10 cities.

To compete in Ford’s challenge, and make the plane more reliable in general, Fokker had the F.VII redesigned to have 3 engines, adding two mounted on the side struts.

The new F.VIIb/3m, decked out here in Sabena colors and flying over Brussels, became immediately popular, with 154 of them built.

Each of the three engines was a 200 hp Wright J-4 Whirlwind. Don’t miss the Brussels Atomium, below to the right.

Belgian tycoon Alfred Loewenstein, calculated to be the 3rd richest man in the world, even owned his own private Fokker F.VII. Flying over the English Channel, in 1928, he had one of the most unfortunate bathroom breaks in history.

You see, the door to the bathroom (left) is directly across from the door to the outside (right). It seems he opened and walked through the wrong one, and fell to his death in the water below. Though to this day, some still suspect it was murder.

If you’re really interested, there’s even a book about this mysterious event:

If that were the sum of the F.VII’s history, it might be pretty uninspiring, but to tell the rest of it, I’m here at Spitsbergen, in Norway’s Arctic archipelago of Svalbard, for Richard Byrd’s flight to the North Pole.

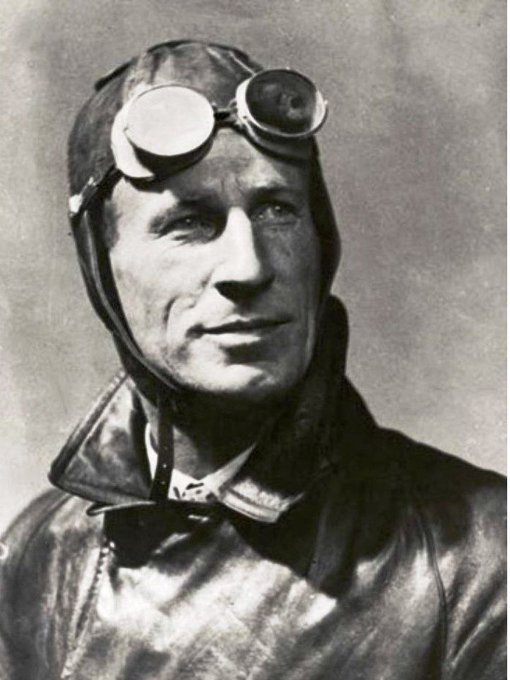

Richard Byrd was a US naval officer who commanded air patrols out of Halifax, Nova Scotia during World War I. He played an active but supporting role in the first attempts to cross the Atlantic by air, and now, in 1926, had his big shot at fame.

His Fokker F.VIIa/3m, mounted on snow skis, was named the Josephine Ford, after the daughter of Edsel Ford, who helped finance the expedition.

This was a two-man expedition, with Byrd accompanied by Navy Chief Aviation Pilot Floyd Bennett. The passenger seats were, of course, torn out and replaced with extra fuel tanks and emergency supplies.

The inside of the cockpit is quite similar to the one-engine version, but with three separate throttles and tachometers (showing RPM).

Of course, there was no airport in Svalbard at the time. They just had to take off from a snow-covered field – hence the skis.

Byrd’s flight, from Svalbard and back, took 15 hours and 57 minutes, including 13 minutes spent circling at their farthest north point, which Byrd claimed, based on his sextant readings, to be the North Pole.

Did he really reach the North Pole, and become the first person to fly over it? This remains hotly disputed to this day, with some researchers claiming that he faked his sextant readings and fell short of his goal.

In that case, the true prize would belong to the Norwegian Roald Amundsen, already the first person to reach the South Pole by land, in his airship Norge.

A few observations about flying the Fokker F.VII, at least in the sim. First, it’s not very stable, in the sense of wanting to correct back to straight and level flight. It’s very sensitive to being loaded either nose-heavy or tail-heavy, and requires a lot of control input.

Second, that big wing really likes to glide. To descend without over-speeding, I basically have to put all three throttles back to idle and glide down.

Coming in for a landing here back at Svalbard. Power is back to idle and I’m gliding in.

Last, there are no differential brakes and no tail wheel. That makes the F.VII very hard to control on the ground, even just to taxi. That’s especially true on snow skis! Here I am doing a ground loop in the snow after landing.

Here are some good views of the open wires connecting the cockpit controls to the elevators and rudder on the tail. As I mentioned, in the sim they actually move, which is kind of cool.

Whether Byrd truly did reach the North Pole or not, he became a huge national hero when he returned to the US. Byrd and Bennett were both presented with the Medal of Honor by President Coolidge at the White House.

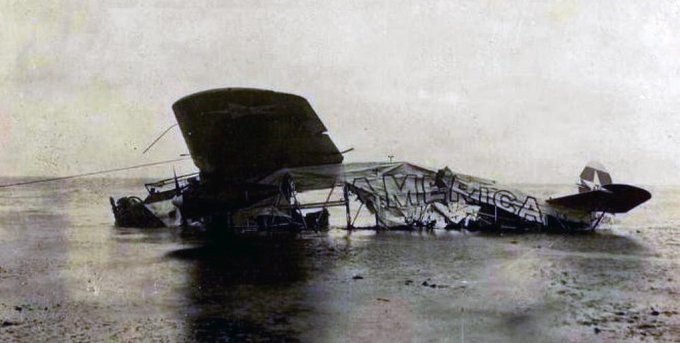

The following year, in 1927, Byrd outfitted a new Fokker F.VII/3m, named the America, to bid for the Orteig Prize, promising $25,000 for the first non-stop flight from New York City to Paris (or vice versa).

Anthony Fokker himself had recently moved to the United States, and was part of the team preparing Byrd and his crew – the odds-on favorites – for the Atlantic crossing.

During practices, however, the America – piloted by Fokker himself – crashed, injuring both Byrd and Bennett and postponing their attempt.

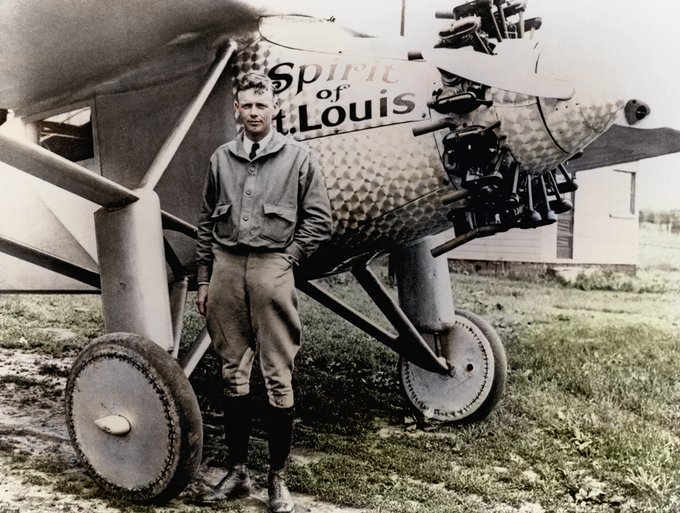

As a result, while the America was being repaired, Charles Lindbergh – an unheard-of underdog – made the flight solo in the Spirit of St. Louis, becoming an aviation legend.

The Fokker F.VII would still achieve fame, though, crossing a different ocean, at the hands of Australian pilot Charles Kingsford Smith, the very next year: 1928.

If you’ve ever passed through Sydney’s international airport and wondered who it’s named after, you’re about to find out. (If you’re an Australian, you already know).

Movie-star handsome Charles Kingsford Smith, aka Smithy, fought as a sapper at Gallipoli in World War I, but soon joined the Royal Air Force as a pilot. He was shot down, injured, and returned to be a flying instructor in Australia.

From that day, Smithy had a dream: to cross the Pacific Ocean by air, from America to Australia. It took him many years to achieve it, but by 1928 he was ready to try.

That’s why I’m here at Oakland Municipal Airport, where he took off, in his Fokker F.VIIb/3m “Southern Cross”.

Not unlike Byrd’s plane, the inside has been altered to make space for extra fuel tanks.

At 8:54 a.m. on May 31. 1928, Kingsford Smith and his 4-man crew lifted off from Oakland, California on the first leg of their journey, to Hawaii.

Flying to Hawaii, much less Australia, was an extremely daunting prospect at the time. While they had a radio, with limited range, there were no radio beacons to guide them.

They could only estimate a course based on the latest, often inaccurate, weather reports over the Pacific, and hope that unexpected winds wouldn’t blow them off course and make them miss Hawaii entirely.

As they flew over the Golden Gate – the bridge hadn’t been built yet – they knew that several aviators before them had estimated wrong and simply vanished into the vastness of the Pacific.

The first stage, from Oakland to Hawaii, covered 2,400 miles, and took 27 hours, 25 minutes (87.54 mph). It was uneventful.

But one can only imagine their joy as they arrived here, over the northeast shore of Oahu.

Looking for Wheeler Army Air Field, in the center of Oahu, where they landed.

Once again, gliding on in with power at idle.

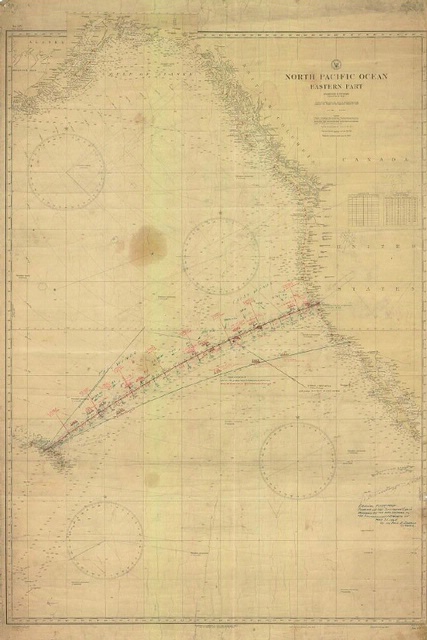

Here’s an image of the navigation chart Kingsford Smith used to get from California to Hawaii.

The Southern Cross was the first foreign-registered airplane to arrive in Hawaii, and was greeted at Wheeler by thousands of people, including Governor Farrington. Kingsford Smith and his crew were put up at Honolulu’s pink Royal Hawaiian Hotel to rest for the next stage.

The runway at Wheeler was too short for the Southern Cross to take off fully loaded, so they flew to Barking Sands on the west coast of Kauai, where a special runway had been constructed.

They took off from Barking Sands at 5:20am on June 3, bound for Suva in Fiji.

The journey from Hawaii to Fiji was 3,155 miles – the longest flight yet over continuous seas.

It lasted 34 hours 30 minutes, an average speed of 91.45 mph.

Halfway across, near the equator, the Southern Cross encountered a tropical thunderstorm.

Keep in mind, they did not have an artificial horizon. The only way they could keep level, flying blind, was keeping a close eye on their airspeed, altitude, and the inclinometer (or turn indicator).

Somehow they weathered the storm and kept going.

They undoubtedly felt great relief when they spotted the green landscape of Fiji ahead.

I’ve located Suva’s modern international airport, just up ahead.

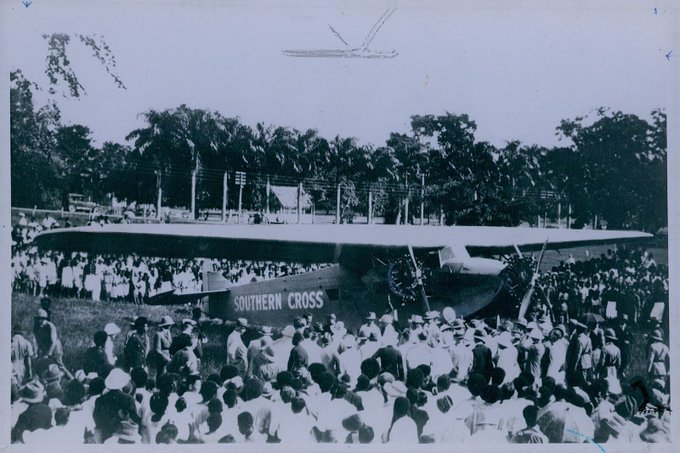

There was no airport at that time, so the Southern Cross landed on a cricket field.

A photo of the Southern Cross arrived in Fiji.

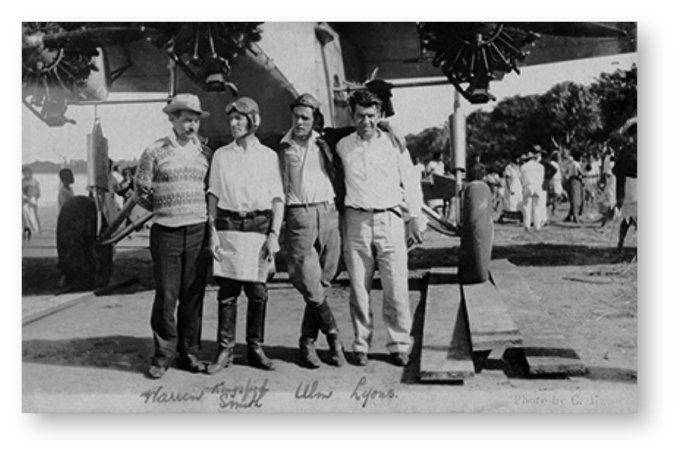

Kingsford Smith and his crew in Suva, Fiji.

Once again, the cricket field where they landed was far too small to takeoff again, so after a few days rest, they relocated – unlike me – to a beach from which to depart for the next and final leg of their journey.

Leaving Fiji on June 9, they embarked on their final 1,683 mile stretch home to Australia.

Once more they encountered storms, which blew them nearly 150 miles off course.

Even when the weather was clear, the unrelenting and trackless ocean must have been overwhelming.

…

…

…

…

The Southern Cross reached the Australian coastline near Ballina, well south of their intended target, and turned north towards Brisbane.

As they reached Brisbane, they were greeted by an aerial escort.

I’m sure the buildings weren’t quite as tall then.

Their goal was Eagle Farm Airport, northeast of the city – now the location of Brisbane’s main international airport.

The Southern Cross had flown 7,187 miles (11,566 kilometers) in 83 hours and 72 minutes. The Pacific Ocean had been conquered by the air, for the very first time.

A crowd of 26,000 greeted Kingsford Smith and his crew when they touched down at Eagle Farm.

Did I fly the whole thing? The hell I did. But I flew enough of it to get an appreciation for what they did.

Kingsford Smith died in 1935, at age 35, when his plane disappeared over the Indian Ocean while attempting to break the England-Australia speed record. His subsequent career was filled with both triumph and scandal, but he survives as Australia’s great aviation hero.

If you visit Brisbane’s airport, you can still see the real Southern Cross on display in a dedicated hangar.

The Fokker F.VII continued as a popular airliner into the 1930s. However, the vulnerability of its fabric and wood construction became apparent following a 1931 TWA crash which resulted in the death of famed Notre Dame football coach Knute Rockne.

As a result, the Fokker F.VII gave way to all-metal airliners like the Boeing 247, Lockheed L-10 Electra, and eventually the DC-3.

One of the most popular successors to the Fokker F.VII was the Ford Trimotor, basically an all-metal version of the F.VII. For all their sponsorship, the Fords seem to have gotten something out of it in the end.

Anthony Fokker lived most of the rest of his life in the United States, and died at age 49 in New York in 1939 from pneumococcal meningitis. His nickname was “The Flying Dutchman”.

Thanks for joining me on this adventure. If you know of any other interesting facts or stories I’ve missed, please add them!

Leave a Reply