April 3, 2023

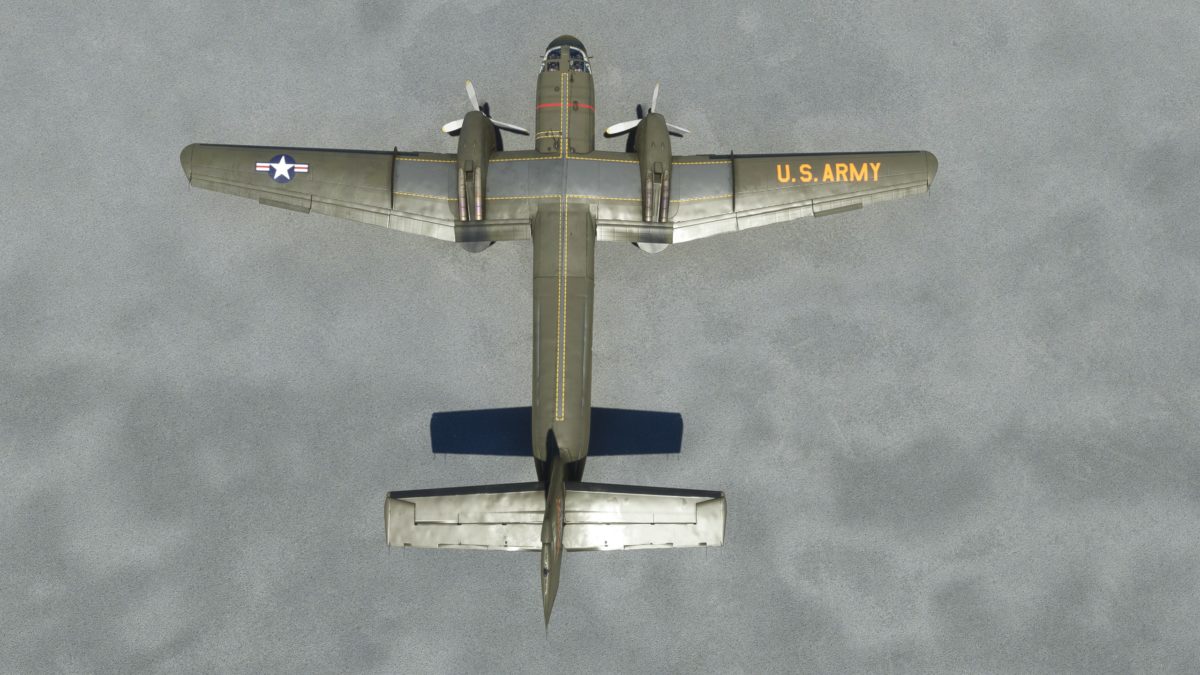

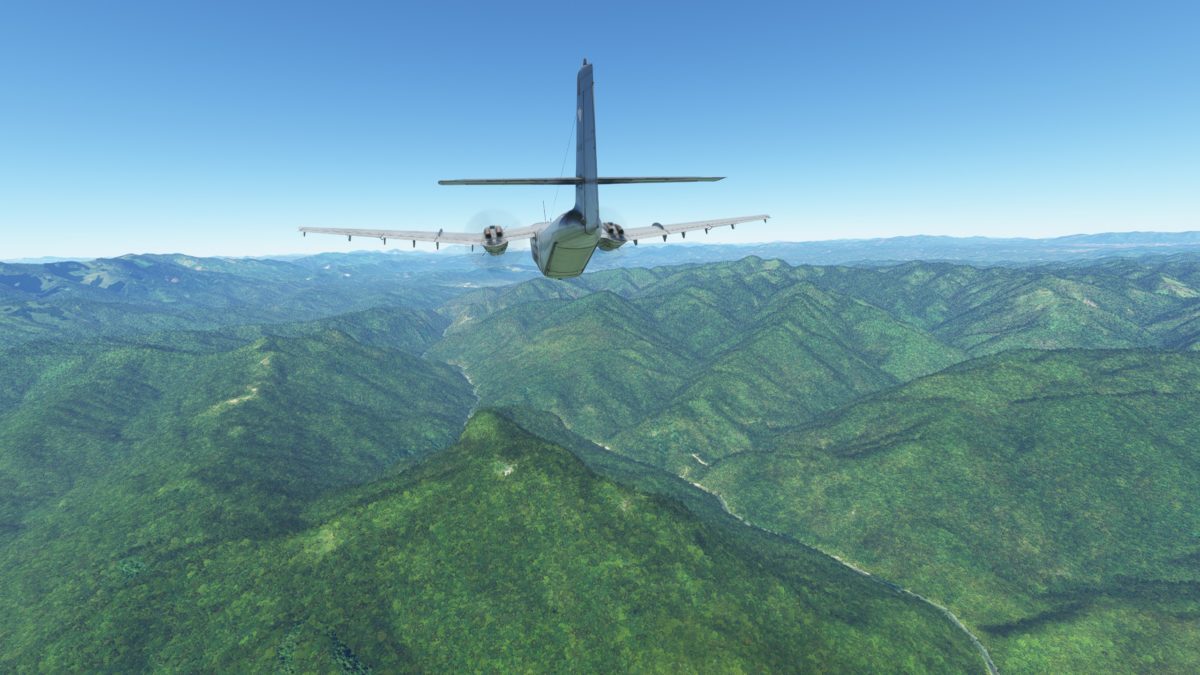

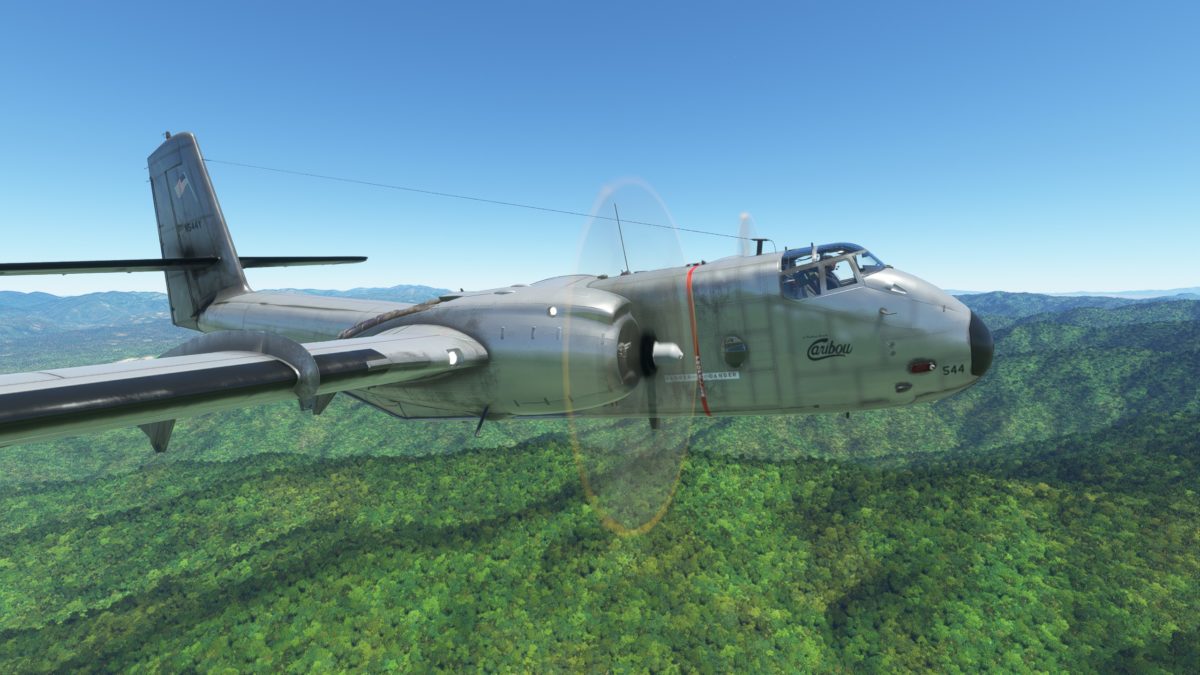

Today in Microsoft Flight Simulator, I’m going to be flying the DHC-4 Caribou, a short-takeoff-and-landing (STOL) cargo plane that played a vital role supporting combat troops and covert operations during the Vietnam War.

In 1956, the U.S. Army put out a request for a new airplane that could carry a DC-3’s load of supplies or troops, but to the short, rugged airstrips typical of remote areas or near the front lines.

As I’ve related in another post, the British-owned De Havilland company established a subsidiary in Canada in the 1930s, mainly to build Tiger Moths to train pilots from across the Empire at a safe distance from the front lines of World War II.

After the war, De Havilland Canada produced the DHC-2 Beaver, a small, rugged STOL plane designed to access the remote Canadian wilderness, but which also found a role on the battlefield, serving the U.S. in the Korean War and the French in Indochina.

The creation of the separate U.S. Air Force in 1947 placed limits of the size of fixed-wing airplanes the U.S. Army could fly. However, due to the rising focus on Cold War counterinsurgency operations, the Army was granted a waiver.

The DHC-4 Caribou weighed in at 18,260 lbs and could carry a payload of 8,740 lbs.

That could include up to 32 soldiers, 26 fully-equipped paratroops, or 22 stretchers along with attending medical personnel.

It had a wingspan of 95 feet 7.5 inches, and was 72 feet 7 inches from nose to tail.

The Caribou was De Havilland Canada’s first twin-engine plane, featuring the same Pratt & Whitney R-2000 Twin Wasp air-cooled radial engines as the Douglas DC-4, each producing 1,450 horsepower.

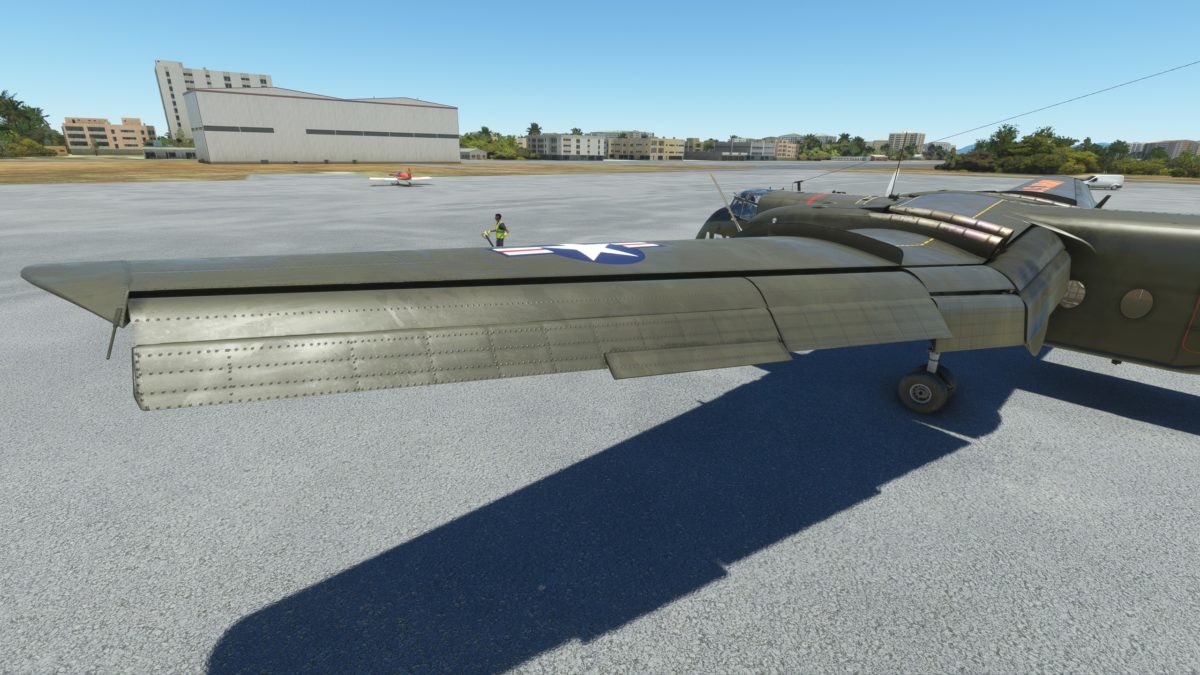

The exhaust from the engines was released directly over the wing flaps, which increased their effectiveness in providing lift.

The flaps themselves could be lowered down to 40 degrees, to minimize takeoff and landing distance. But pilots rarely lowered them the whole way, as this reduced the control effectiveness of the ailerons, which got extended and lowered with the flaps.

The cockpit of the Caribou was raised a step above the cargo deck and had overhead glass for improved visibility.

The Caribou had at least three crew. A captain (left) and co-pilot (right) sat in the cockpit.

A flight engineer doubled as loadmaster and aircraft technician. He stood behind and between the two pilots on takeoff and landing, and sat in the cargo section for most of the flight.

Additional “technos” could ride along depending on the mission, to assist with in-flight breakdowns or cargo handling (including parachuting or just throwing cargo out the rear ramp).

The throttle (large white handle), prop, and mixture controls are located overhead, between the two pilots. So is the lever controlling the flaps (upper left).

That leaves more room for the radio panel on the floor between the two pilots.

The yoke and rudder pedals for each pilot are connected by cables to the ailerons, elevators, and rudder. No hydraulics or fly-by-wire here. Pilots reported that controls were quite light up to 120 knots airspeed, beyond which they required some exertion to operate.

Except for the location of the turn indicator (down and left, replaced by a radio navigation gauge) and heading indicator (to the bottom right), the main flight instruments are arranged in the now-standard “six pack”.

An interesting addition, at top directly above the “six pack”, is a special dial showing whether approach speed is too fast or too slow for an optimal short field landing with full flaps. We’ll see how useful that is in a bit.

At the center of the panel, between the two pilots, are the engine gauges. I’ll be keeping a particularly close eye on the two at the very center, showing Manifold Pressure (engine power) and RPM.

There’s an elevator trim wheel by the pilot’s left knee, along with an oxygen hook-up for higher altitudes – though as we’ll see, the Caribou typically didn’t cruise above 10,000 feet.

In front of the pilot’s left knee, below the turn coordinator, are the switches for starting the engines.

And behind us, on the back wall, are the circuit breakers for all the plane’s electrical systems. The switches for operating the rear ramp are at the bottom right, and I’ll be using them today.

Alright, co-pilot, let’s get these engines started and get going.

Unusual for a piston-driven plane, the thrust of the propellers can be reversed, which helps bring the Caribou to a faster halt on landing. Before departing, we always test them out to make sure they’re working properly.

The U.S. Army ordered 173 Caribous in 1959 and began taking delivery of them in 1961, designating them the CV-2.

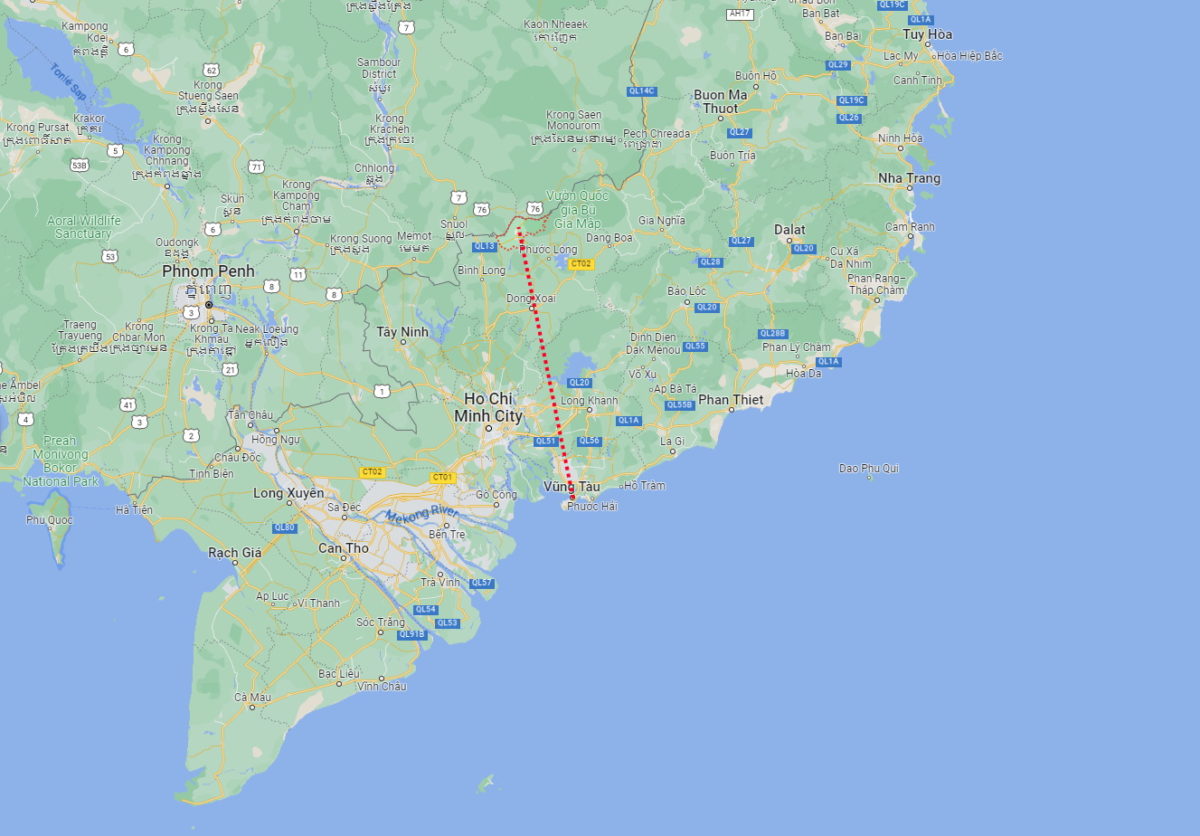

They arrived just in time to be sent to South Vietnam, starting in 1962, to support Special Forces advisors training that country’s military. They were initially based here at Vung Tau, on a peninsula east of Saigon.

With flaps down 25 degrees, once the Caribou reaches 63 knots you pull back on the yoke to take off. A fully-loaded Caribou can get off the ground in about 725 feet.

Soon after taking off from Vung Tao, I gradually lift the flaps, pull the throttle back to 35 inches of manifold pressure, and pull the prop back to 2250 RPM, for a steady climb at 105 knots.

The mission today is to fly almost straight north to resupply the Special Forces camp at Bu Dop, right on the border with Cambodia. The trip should take roughly an hour.

Here is the planned route on the map, in red.

Passing through 5,000 feet, I skirt the northern edge of the Mekong Delta.

Every thousand feet of altitude, I need to nudge the throttle upwards to keep manifold pressure at 35, as the air density decreases.

I’m leveling off at 10,000 feet, a standard cruising altitude for the Caribou. While the plane has a service ceiling of 24,800 feet, its single-stage supercharger can only maintain 35 inches of manifold pressure up to that altitude, even at full throttle.

So this is my optimal cruising altitude. I’ll lower the nose to level, reduce the throttle 31 and the RPM to 1900, and let the airspeed rise to 120 knots.

The “never exceed” speed of the Caribou, which is posted all over the cockpit, is 208 knots. But for safety and fuel efficiency, we’re staying around 120 knots indicated airspeed, which at 10,000 feet equates to 140 knots true airspeed because of the thinner air.

One key fact about the Caribou is that it did not have any autopilot. It had to be actively flown by the pilots the whole time. No rest for the wicked, even at cruising altitude.

Still, there space in the back for one pilot to rest on particularly long hauls, and a “relief tube” in the rear of the cargo compartment for when nature calls.

The range of the Caribou depends on what it is carrying. With a maximum fuel load of 830 gallons, it can go over 1,300 miles. But weighed down heavily with supplies, it might only have a reach of 240 miles.

Fortunately we are well within those limits today, and it’s not long before I pull the throttle and RPM back slightly and begin our gradual descent.

The U.S. Special Forces camp at Bu Dop was established in November 1963, and came under repeated Viet Cong attack as the war escalated. It wouldn’t be on any GPS even if I had one, so I need to keep my eyes out.

There it is: a fortified firebase with a dirt airstrip next to it.

Now I need to circle back – without crossing over into Cambodia – and reduce speed to safely land. Flaps and gear can come down anywhere below 120 knots.

I’m lined up now on final approach, with 35 degrees of flaps. Speed should be 80-85 knots. Note that the indicator at the top center of my instrument panel shows that speed is on-target for a short field landing.

Stall speed is 59 knots, but you don’t gently stall a plane like this over the runway, you plunk it down, as soon as possible. The landing gear is built to take it.

In fact, though it’s not recommended, the Caribou can land nose-gear first. Here’s a video of a DHC-4 “doing the wheelbarrow”:

Then the moment it plunks down, you stomp on the brakes and put the propellers into reverse thrust. Those two little red lights near the top of the instrument panel show they are in reverse.

A fully-loaded Caribou can come to a halt in 670 feet. With the fuel we’ve burned on the way here, we could ideally stop in just 525 feet. Looks like I’m pretty close. I certainly had plenty of runway left.

A Caribou sitting on a dirt runway outside a firebase was an open invitation to attack. So often they didn’t bother to shut down their engines, they just pulled up and threw their delivery out the door.

Time to reach behind me, raise the cargo door, and lower the ramp.

Despite its versatility, the carrying capacity of the Caribou was limited. The Battle of Ia Drang Valley in 1965 made it clear that Caribous alone could not support a large Army unit in combat in the field. For that, the Army needed the Air Force’s help.

But the Caribou was suited to drop off a few critical supplies (including morale-boosting treats) and ferry out wounded from a remote forward base like Bu Dop.

And this is precisely what the Caribous – also known as “Gravel Trucks” or “Boos” – did, all day every day, on short hops from base areas to the front lines.

Which is why, in a matter of minutes, I’m on my way again, heading back to Vung Tau or wherever else the next supply run awaits.

But the Air Force was never happy with the Army operating a fixed-wing airplane like the Caribou, and after Ia Drang it began to complain vigorously about it as an inefficient use of resources.

So in January 1967, the Army handed over its 134 Caribous still service, like this one here, to the U.S. Air Force. They remained in Vietnam, just under different management.

The Air Force dispersed the Caribous, which it dubbed the C-7, to other bases throughout South Vietnam. This one was sent to the newly-formed 458th Squadron here at Cam Ranh Bay, a major U.S. naval base.

This particular Caribou was given the name “Pamela Ferne” in tribute to the 10-month-old daughter of its crew chief Stoney Faubus.

I actually looked her up, and sadly she passed away last year. Her father appears to be still alive.

https://www.legacy.com/us/obituaries/avpress/name/pamela-cuellar-obituary?id=33511146

The Air Force integrated the Caribou into its larger airlift capacity in Vietnam, and allocated the specifically to the kind of forward airfields (like Bu Dop) that couldn’t handle larger planes.

Here’s a video of an Air Force Caribou delivering “bullets, beans, and mayo – the three necessities of life” to Trabong Firebase, to some jazzy 1960s action music.

At Christmas, the Air Force painted the noses of their Caribous red, like Rudolph the Reindeer. The so-called “Santa-bous” delivered decorated trees, eggnog, Christmas cookies, and ditty bags to soldiers in forward combat units.

Starting in 1970, the U.S. Air Force started demobilizing its Caribou squadrons in Vietnam. Some were given to the South Vietnamese, while other were sent to Reserve units back in the States.

The “official” war was hardly the only action the DHC-4 Caribou saw in Southeast Asia. That’s why I’m here at a remote airstrip in Laos with an outfit called “Air America”.

Most people have heard of Air America from the 1990 film starring Mel Gibson and Robert Downey Jr. It’s controversial, because not everyone agrees with its portrayal of the group or its activities.

The story of Air America begins in early 1941, with the formation of the American Volunteer Group (AVG), better known as the Flying Tigers, US pilots who flew covertly for China against the invading Japanese.

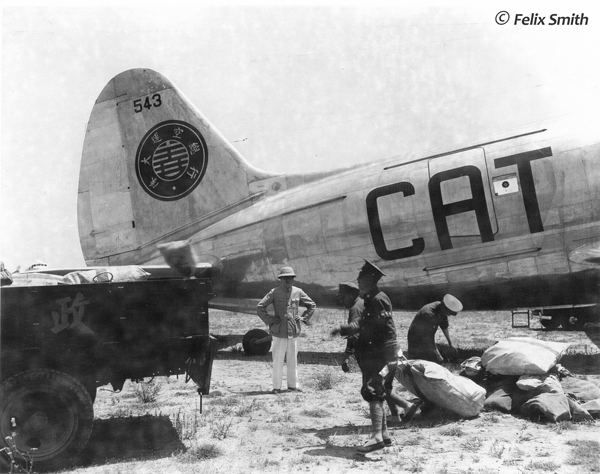

After the war, its leader, Claire Chennault, bought surplus planes to form an airline called Civil Air Transport (CAT) to help ferry Nationalists troops to battle the Communists during China’s Civil War.

When the Nationalist fled to Taiwan in 1949, CAT went with them. Outwardly, it was a normal airline, but secretly the CIA bought control of it as a front for covert operations in Asia.

CAT pilots transported supplies during the Korean War, dropped agents in mainland China, and helped supply the French troops besieged at Dien Bien Phu.

Starting in 1959, CAT was reorganized as Air America and began providing logistical support for US Special Forces training Royal Laotian forces, and later Hmong tribal militia who were hostile to the Communist Pathet Lao and North Vietnamese.

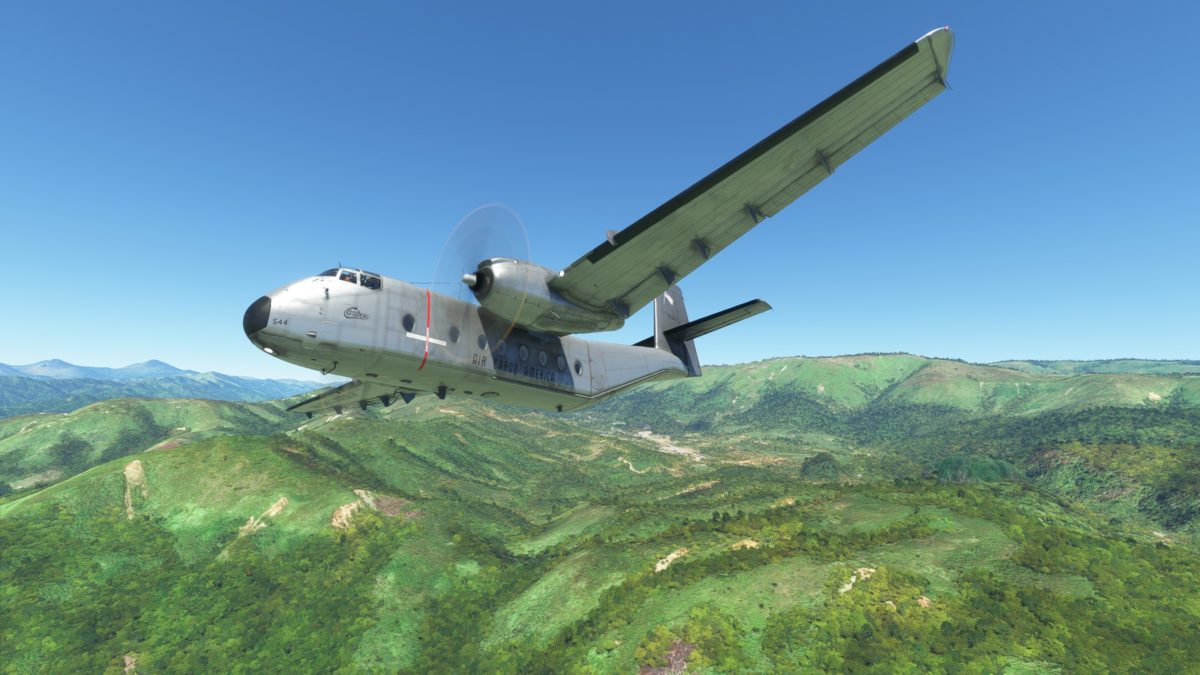

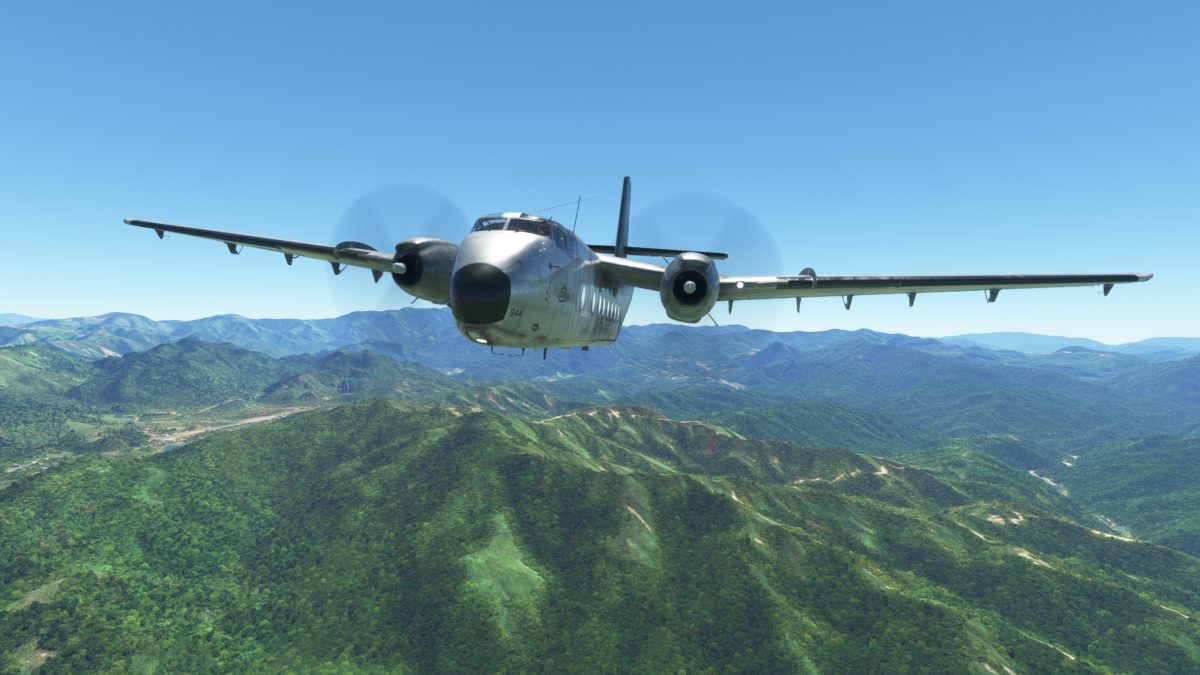

Air America flew a wide range of aircraft in Laos, including the Pilatus PC-6 Porter, the U-10D Helio Courier, and the Bell 206 helicopter. But the DHC-4 Caribou, when it arrived in the early 1960s, was the heavy lifter of the bunch.

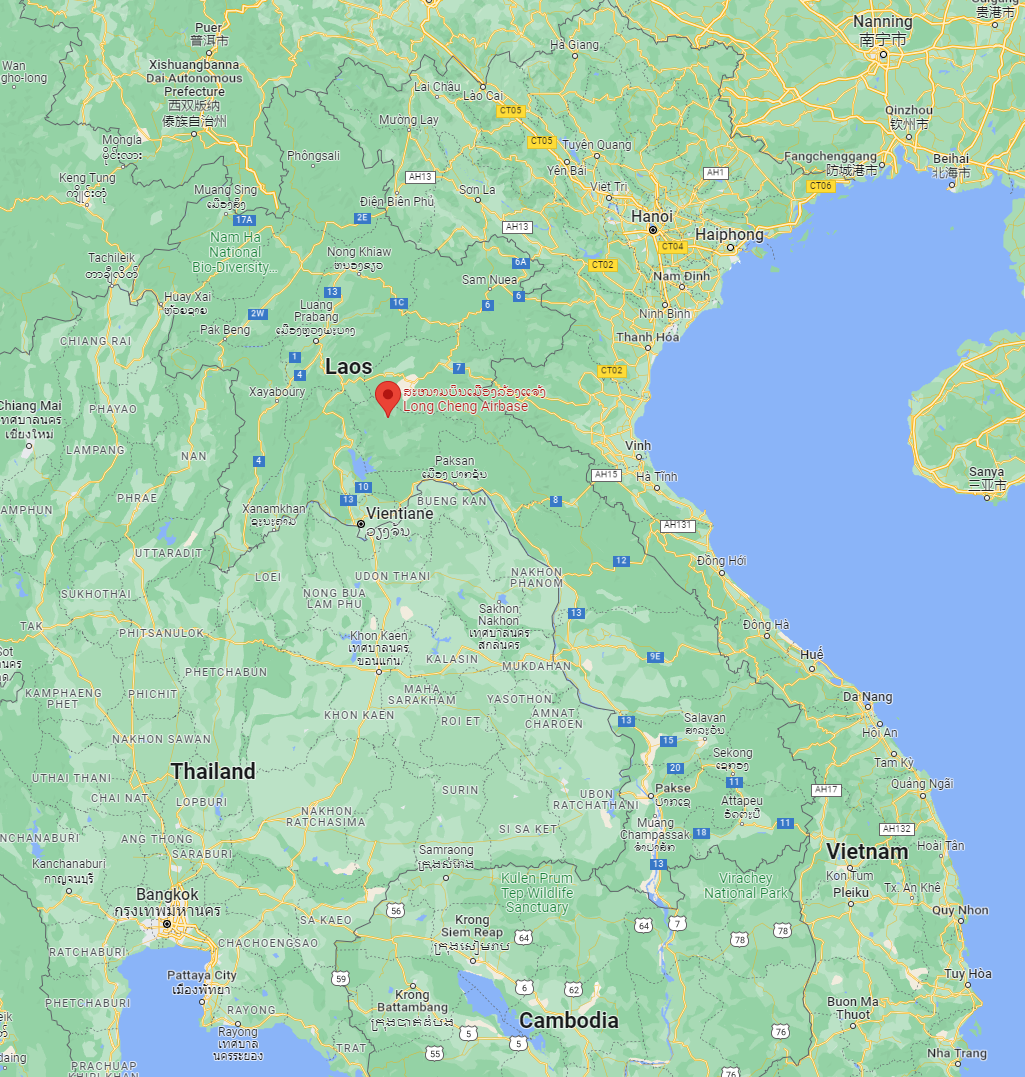

This one is parked at Long Tieng, the secret headquarters of the Hmong warlord General Vang Pao. Hidden high in the mountains, at an elevation of 3,250 feet, it is actually the busiest airport in Laos, and that main road through town is the runway.

Known as Lima Site 98 (LS 98) or Lima Site 20A (LS 20A), Long Tieng was the hub for covert Air America operations across Laos. Aircraft flew in and out at all hours carrying supplies, arms … and possibly drugs.

Here’s a map showing Long Tieng’s location. Though it didn’t appear on any map at the time, with a population of 40,000 the secret base became Laos’ second largest city.

“What a place is Long Tieng,” wrote a USAID worker. “Tribal soldiers dressed in military garb standing next to traditionally dressed Hmong, with Thai mercenaries milling about. And the Americans here are mostly CIA operatives with goofy code names like Hog, Mr. Clean, and Junkyard.”

Regardless of which way the wind is blowing, there’s only one way in and out, because of the surrounding mountains. And there are no go-arounds. You get one try.

It’s exactly the kind of airstrip the Caribou was made for. And I’m starting to get a feel for the short takeoffs now.

There are three components of the mission today. First, I’m going to parachute some supplies over a remote area. Then I’m going to land at two other Lima sites to make some deliveries.

To do that, I’ve turned around to head north, following the valley of the Nam Ngum River. Behind me, to the left, you can just see the airstrip at Long Tieng nestled in the hills.

Today just happens to be a beautiful day, with barely a cloud in the sky. That’s great for our sightseeing, but Air America pilots often had to navigate these remote mountainsides while dodging low-lying clouds and monsoon rains.

We’re approaching our drop location, so I’ve opened up the cargo door in-flight. Air America often hired local Hmong to work as “kickers”, pushing deliveries out the door on the pilots’ signal.

Airdropped deliveries often included bags of rice (dropped without a parachute) as well as “hard rice” (aka, ammunition). Flying low and slow, the Caribou could hit a drop zone within 100-150 feet – far more accurate than larger planes.

With our first delivery complete, I close the door back up and continue following the river north. The next stop is the village of Xieng Dat, known as Lima Site 26.

Did Air America also transport opium and heroin for international export, as portrayed in the movie? Accounts differ. Some pilots and researchers say that they did, or at least turned a blind eye. Others adamantly reject such reports as salacious slander.

Opium was so central to the region’s economy, and the livelihood of its hardscrabble tribal farmers, that it would have been difficult to avoid encountering it entirely. But whether the CIA actively encouraged or participated in the trade is a hotly disputed question.

And it’s one we won’t have time to resolve before arriving at LS26, up ahead. (Even today, on Google Earth, you can still see faint traces of where the airstrip used to be).

There were at nearly 40 Lima Sites sprinkled across the highlands of Laos, some with runways as short as 800 feet (this one, in contrast is a relatively long 4,000 feet).

Unlike the firebase airstrips in South Vietnam, which at least were designed and constructed by Army engineers, the Lima Site airstrips were constructed by local people, to much more “improvised” standards.

It’s tricky under ideal circumstances. Now imagine it in a foggy downpour. Now imagine taking unexpected ground fire from some enemy hidden nearby. Things could get complicated fast.

Deliveries included military supplies, but could just as readily include live animals such as pigs, chickens, or even water buffalo. One pilot said the chickens were the worst, because of the awful smell.

The Hmong (also called the Miao) were hill people, originally from central China, who had migrated over the past few centuries to the highlands of Southeast Asia.

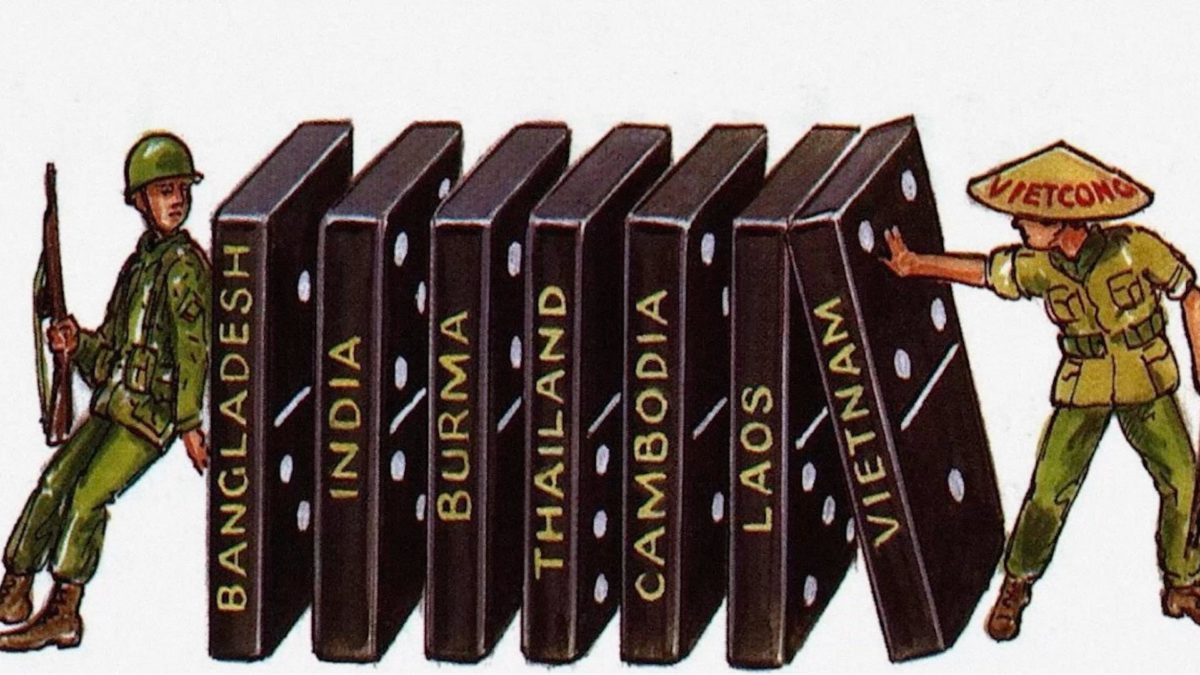

When Laos gained its independence from France in 1954, after the French defeat at Dien Bien Phu, President Eisenhower feared that it could become next in a series of dominoes that could turn all of Asia Communist.

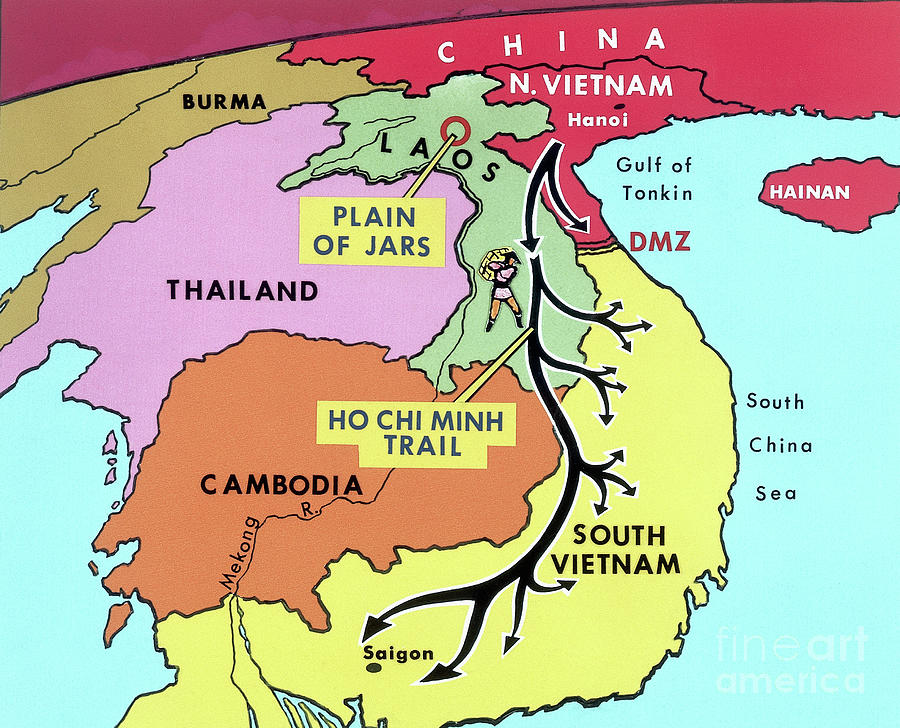

Meanwhile, the east of Laos became a conduit for flows of men and arms from the Communist North Vietnam to support the Viet Cong insurgency in South Vietnam – the so-called “Ho Chi Minh Trail”.

Vang Pao, a general in the Royal Laotian Army, was also an ethnic Hmong and a charismatic leader among his people. The CIA backed him as a way to counter the North Vietnamese and their local Communist allies, the Pathet Lao.

The “secret war” in Laos – including the Air America flight operations – became the largest clandestine operation ever conducted by the CIA, based out of friendly Thailand.

In additional to supplying the Hmong army, Air America pilots transported troops, evacuated casualties, rescued downed U.S. airmen lost on missions over neighboring Vietnam, and conducted surveillance operations over the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

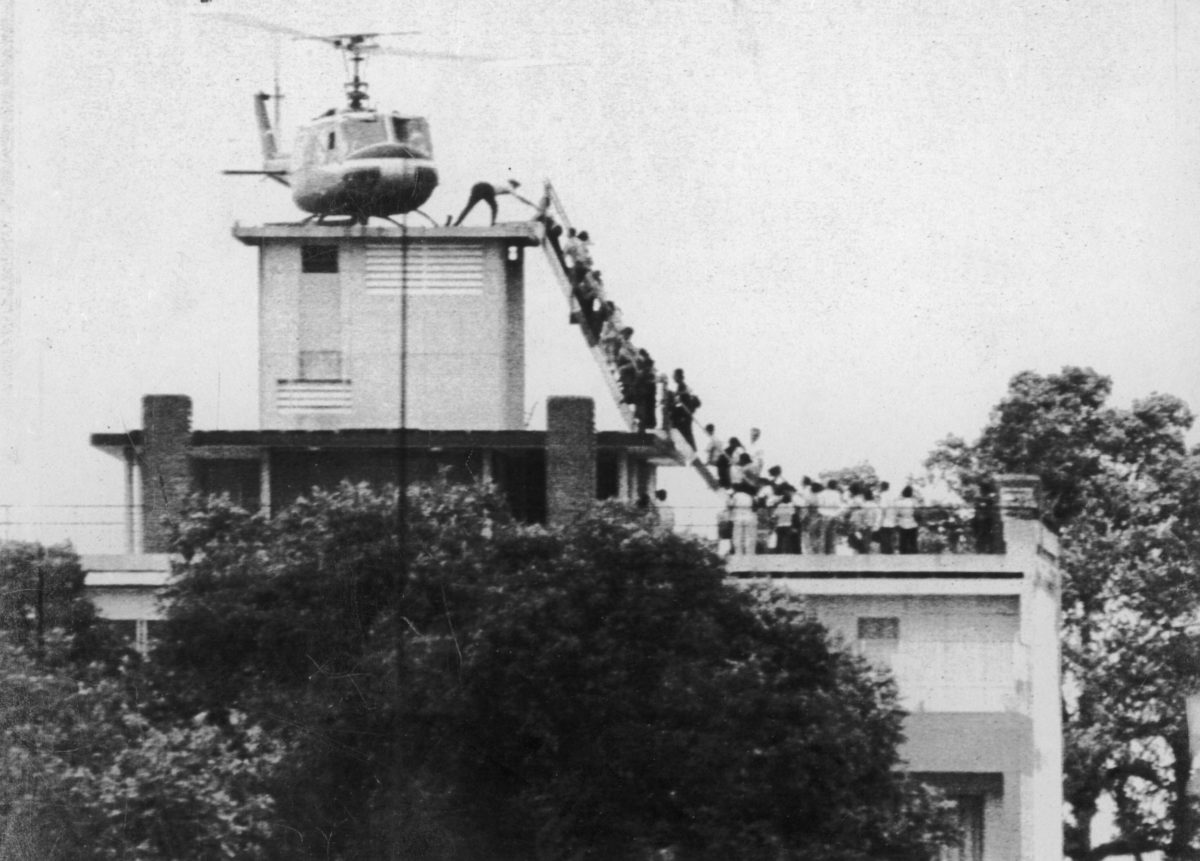

The rooftop helicopter in the famous photo showing the last refugees being evacuated during the Fall of Saigon in 1975 was actually owned and operated by Air America, not the U.S. military.

As late as 1970, Air America had over 300 pilots, air crew, and mechanics working in Laos. That year its planes landed or airdropped 46 million pounds of foodstuffs, mainly rice, in the country.

But with the withdrawal of US troops from Vietnam, the tables in Laos began to turn, and when Saigon fell, the Pathet Lao swept to victory. Over 300,000 refugees, including many Hmong, fled to Thailand. Many ultimately settled in the U.S.

Air America was dissolved in 1976 and its assets sold to another charter airline with close CIA ties. So what to think about its legacy in Southeast Asia?

I think it’s fair to say that the portrayal of the company’s pilots in the film – as a group of reckless, cynical mercenaries used as mere pawns by the CIA – gave a misleading impression.

Based on interviews and documentaries I’ve seen, most were apparently consummate professionals, calm and steady under pressure, who believed strongly in what they were doing. Whatever you think of their mission, they probably deserve to be remembered as such.

In any case, we’re nearly to our last stop, an airstrip called Lima Site 20 (LS20) at the village of Sam Thong. The landing strip is 1,900 feet long and 50 feet wide, about the same as where I learned to land a Cessna 172 (and it was small for a Cessna).

Managing the approach is everything. Because I spotted it too late, I was too high. Now I’m coming in “hot” at just over 100 knots – and the hill at the other end means a go-around isn’t an option.

Unable to touch down and brake in time, I over-ran the end of the runway. It doesn’t look so bad from this angle …

But from here you can see what a close call it was. Even with experienced pilots and capable aircraft, many Caribou were wrecked trying to land on these airstrips in Laos. A single mistake could be fatal.

I mentioned other CIA-linked airlines. Another one which made used of the Caribou was Intermountain Aviation, which was based at Marana Army Airfield (now Pinal Airpark) near Tucson, Arizona.

One of the projects the Caribou was involved in was apparently the development of a “sky hook” that could grab and recover an agent from the ground without landing.

This system was depicted, somewhat accurately, in the 1965 James Bond film “Thunderball”, though in this case using a modified B-17 bomber. I say “somewhat” because given the g-forces, he could never have held onto that girl.

I actually flew over Pinal Airpark during my pilot training, on a long-distance cross-country from Phoenix to Marana, and had no idea of what went on there. I suppose they like it that way.

The United States was hardly the only country to make use of the DHC-4’s unique abilities. Starting in 1964, Australia bought 29 Caribous and deployed them to South Vietnam.

This time I’m at Nam Dong, a fortified camp south of Hue and west of Danang, used by American and Australian military advisors to train local militia.

The Australian Caribous in Vietnam were used in a similar capacity to their US counterparts, and became lovingly known as the “Wallaby Airlines”

The Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF), however, retained its fleet of Caribous for many years after Vietnam, deploying them on a host of special forces, humanitarian, and peacekeeping missions.

Australia’s hardy Caribou saw service in Kashmir, Cambodia, Papua New Guinea, and East Timor, as well as domestic disaster relief operations.

The RAAF’s last 13 Caribous were only retired in 2009, after 45 years of service – and many were sorry to see them go, given how well they filled their unique niche.

As I mentioned before, South Vietnam’s air force inherited a number of Caribous when the U.S. departed, and continued using them to shore up its failing defenses.

After Saigon fell, several Caribous fell into the hands of the Vietnam People’s Airforce, which continued to operate them through the late 1970s.

Though they usually acquired them by more conventional means, at least 20 militaries are known to have used the Caribou, including Spain, Malaysia, Sweden, and India – though none are still in operation today.

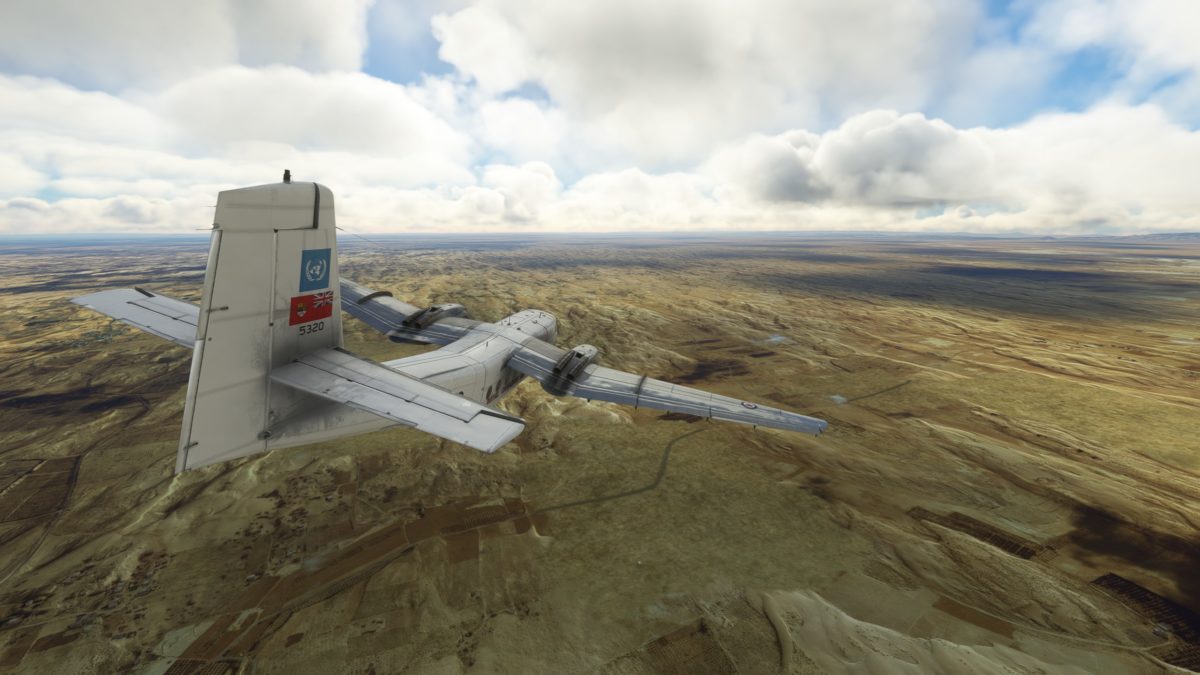

While it was designed and manufactured the DHC-4 Caribou, Canada only purchased a total of nine of them, which were assigned to the 424th Transport and Rescue Squadron.

In the early 1960s, this one was loaned to the United Nations for peacekeeping duty in the Sinai, on the tense border between Israel and Egypt, in the wake of the 1956 Suez Crisis.

The United Nations Emergency Force (UNEF) was based out of Al-Arish, just west of Gaza. Their job was to provide logistical support to UN ground troops as well as aerial observation of any alleged border incursions.

Once again, the Caribou played host to a colorful array of cargo and passengers. One Canadian pilot tells the story of a strange odor wafting into the cockpit during a flight to Beirut …

The Arab passengers had decided to make tea by lighting a fire of camel dung in the back. When the crew used a fire extinguisher to put it out, they were not pleased.

The sand at Al-Arish was permeated with salt water from the nearby Mediterranean coast, which played havoc with the Caribou’s flap hinges. Sand storms and rising convective currents from the 40° heat made flying a challenge.

Canada retired its Caribous in 1971. This particular plane was transferred to Tanzania’s air force, where it flew until 2002, when it was scrapped.

The last DHC-4 Caribou in U.S. service flew in support of the U.S. Army’s Golden Knights parachute team, based here at Fort Bragg, North Carolina.

Originally conceived by General Joseph Stilwell, the team was formally recognized in 1959 and competes in international competitions as well as performing at public events.

The Golden Knights dropped from Caribous until 1985, when they were replaced by DHC-6 Twin Otters and DHC-8 “Dash 8s” – both of them also made by De Havilland Canada.

The DHC-4 Caribou did see some genuine civilian use, usually drawing on surplus planes whose military service was over, in areas where developed airports were few and far between.

In the late 1960s, after Australia’s Ansett bought Mandated Air Lines (MAL) of Papua New Guinea, it operated at least one Caribou on regular routes to that country’s isolated airstrips.

Here I am coming in for a landing at one of them. Hang on.

Most of the airstrips Ansett-MAL served have since been paved and lengthened. So I’m on approach to another airstrip that is more typical of what they would have encountered at the time. And once again, I’m coming in too “hot”.

Fortunately, there runway is sloped steeply upwards, bringing me to a safe stop. In fact, it was so steep I had to go full throttle just to taxi the rest of the way.

At the top of the hill, I found some friendly folks awaiting my arrival.

Time to take off again. Apparently, Ansett-MAL soon halted its Caribou service due to tightened safety rules.

Last that was heard, the plane it once operated was smuggling arms from El Salvador to Nicaragua in 1986. Such is the life of a Caribou.

Overall, De Havilland Canada made 307 DHC-4 Caribous over 10 years, halting production in 1968. Very few, if any of them, are still flying today.

The reason isn’t that they weren’t durable, but the opposite. Because they were built to take a beating, they were “ridden hard and put away wet”, and driven to an early grave.

There’s only so many times you can fly a heavy cargo plane onto rough airstrips hacked out of the jungle for planes half its size, before making a mistake that ends its career.

That’s what happened to this Caribou. The 215th to be built, in 1964, it served in Vietnam for the U.S. Army and later U.S. Air Force. After stints for various charter airlines in Alaska, it ended up with Greatland Air Cargo.

Started in 1995, Greatland hauled cargo from Anchorage to all manner of small, remote airfields across Alaska.

On August 29, 2001, it was on approach to Port Alsworth, Alaska, like I am here.

At the very last moment, a sudden downdraft caused the Caribou to yaw out of control, and it struck trees and crashed. The aircraft was badly damaged and written off as a loss.

Remember the “Pamela Ferne” from Vietnam? It also flew for Greatland in Alaska in the late 1990s, and crashed several times, but somehow survived. It ended up in the Philippines, where last reports have it up for sale for $145,000, with 15,600 hours on its airframe.

A few years ago, someone snapped this photo of a derelict Caribou at Shell-Mera, in Ecuador’s Amazon jungle. We have to use our imagination, and some detective work, to envision it in its heyday.

It turns out this Caribou (the 252nd built, in 1967) was originally intended for the Malaysian Air Force, but was never delivered. Instead, it went to work for a subsidiary of Air America in Southeast Asia.

It kicked around Arizona and Alaska for while, before it ended up flying for Aerolineas Condor in the Amazon.

Regrettably it did not last long before crashing here at the Río Amazonas Airport in 1993. Its wreckage lay there, consumed by the jungle, until it was finally scrapped in 2000.

But we can imagine a safe landing, this time, for the Caribou, its reverse-thrust propellers bringing it to a rapid halt on the runway.

Perhaps it has brought a load of smelly pigs and chickens from a remote Amazon airstrip. Or perhaps a secret load of weapons and drugs. Or maybe just a dozen or so passengers, connecting from their small village to a wider world.

In any case, I hope you’ve come to appreciate this uniquely capable aircraft, the unsung hero of many short takeoffs and landings in remote, often dangerous locations. A dying breed, in all but memory.

Leave a Reply