March 25, 2023

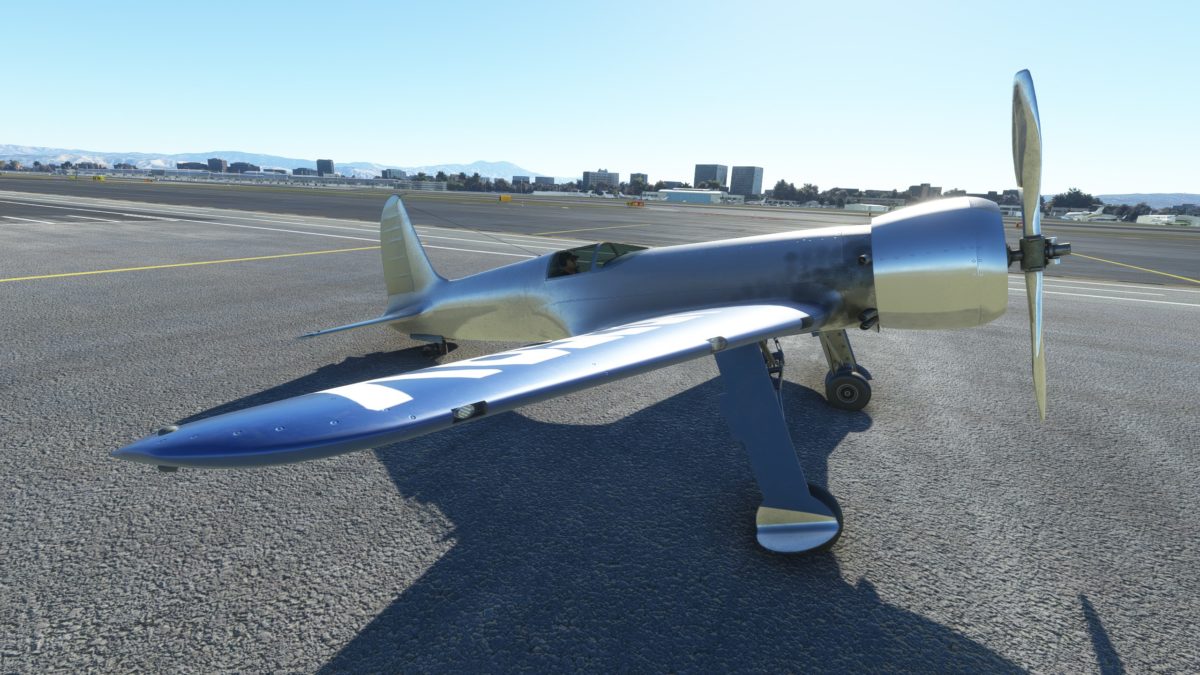

Today in Microsoft Flight Simulator, I’m flying the Hughes H-1 Racer, the superbly streamlined airplane that the eccentric tycoon Howard Hughes built and flew to set several world speed records.

The story of this plane really begins in 1908, when Howard’s father, Howard Hughes Sr., patented a new drill bit that proved essential to the oil boom then sweeping Texas.

The drill bit business generated money like a gushing oil derrick. Hughes Sr. moved his family to California, where his brother (Junior’s uncle) was a successful screenwriter for the fledgling movie industry, interested to get in on the action.

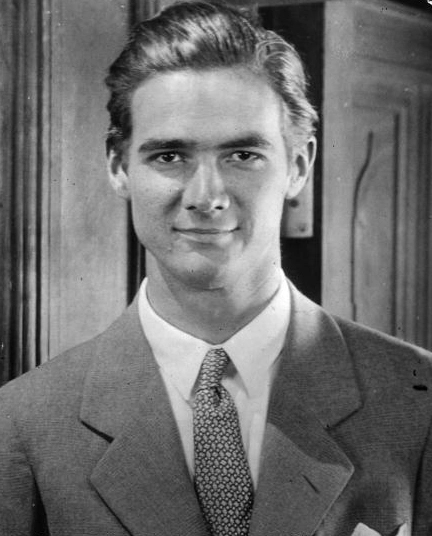

But in 1924, Hughes Sr. suddenly died of a heart attack, leaving his 19-year-old only son, Howard Jr., with a controlling 75% share of the thriving company. Completely uninterested in drill bits, this very young man had big dreams for how to use his new fortune.

He launched an independent movie studio, and began dating the town’s most glamorous actresses, including Joan Crawford, Ginger Rogers, Hedy Lamarr, Bette Davis, Ava Gardner, Olivia de Havilland, and Katharine Hepburn – which didn’t go over very well with his first wife.

Meanwhile, he embarked on filming an insanely ambitious war epic that many believed would ruin him. “Hell’s Angels”, which Hughes directed himself, took an unheard-of three years and $4 million to complete.

The clip from Martin Scorsese’s 2004 movie “The Aviator”, staring Leonardo DiCaprio as Howard Hughes, depicts the filming of “Hell’s Angels”:

Hughes assembled a private air force of over 100 planes and pilots to portray the film’s realistic, action-packed dogfight scenes. When it was finally release in 1930, it was a huge hit, receiving a nomination for the Academy Award for Best Picture.

In the process, Hughes became interested in learning to fly himself. He even worked incognito as a mechanic to learn the ropes from some of the best pilots and designers in the aviation industry.

To gain experience, he even secretly got a job with American Airlines as a pilot. He made on trip from Los Angeles to New York before his identity was discovered and he was forced to resign. This is a real photo of him in his uniform:

He became interesting in racing, and in 1934 founded a new company, Hughes Aircraft, solely to build a custom-made plane that could set new world speed records. That plane was the H-1 Racer.

The H-1 was fitted with a Pratt & Whitney Twin Wasp Junior radial engine, the same used by the Grumman F3F fighter. Normally capable of producing 700 horsepower, it could produce 900 hp when fed with high-grade 100-octane fuel. Unusual at the time, this later became standard for aviation gasoline (Avgas).

The drawback of an air-cooled radial engine, compared to inline pistons, was that it creates drag. However, the H-1 minimized this with a bell-shaped cowling that streamlined the air around it.

The fuselage was constructed of strong, lightweight duralumin, an alloy consisting of 95% aluminum, 4% copper, 0.5% manganese, and 0.5% magnesium.

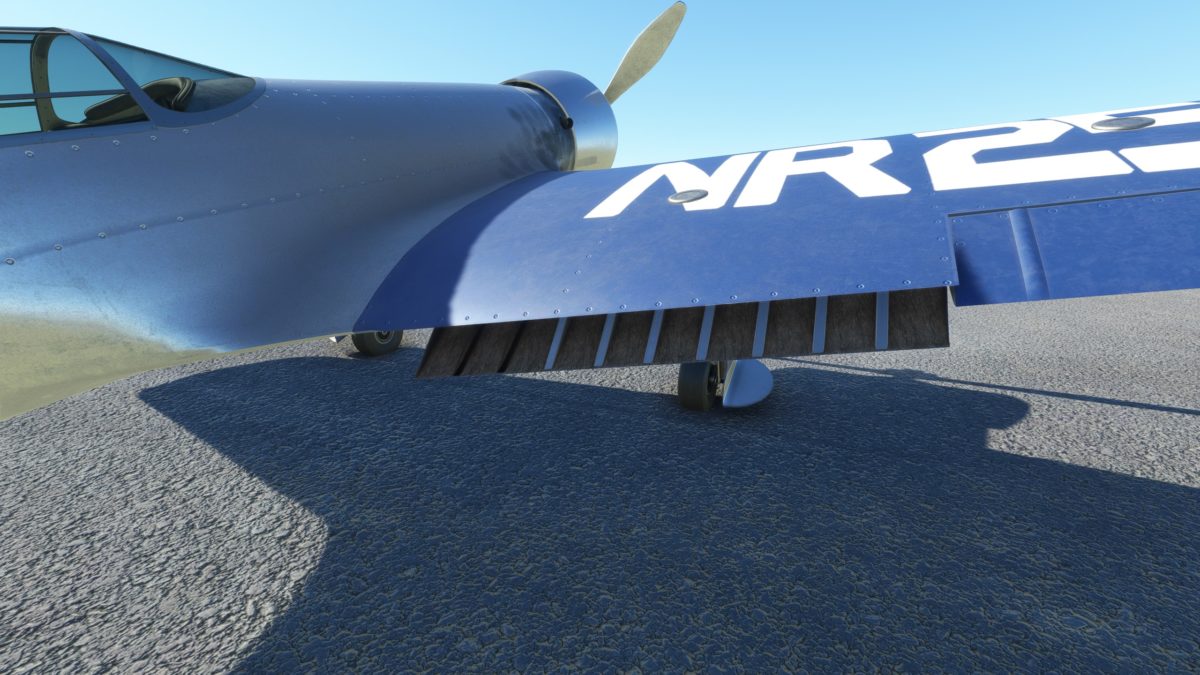

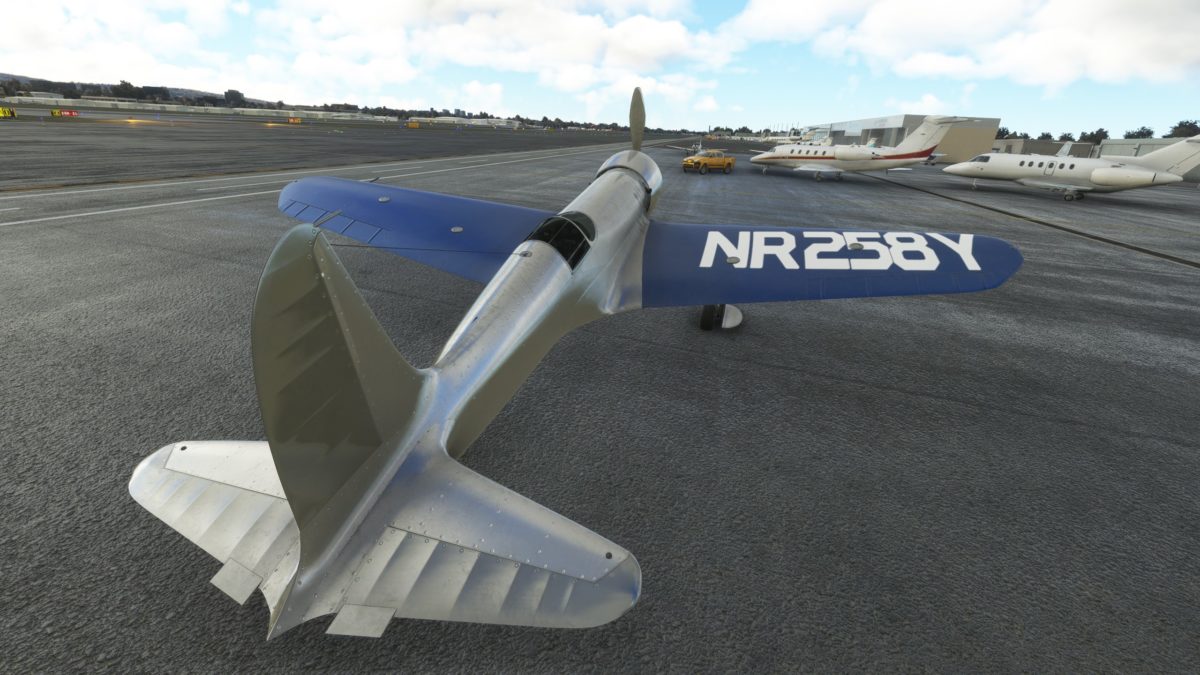

Streamlining was an obsession. Every rivet on its surface had its head partly sheered off so it lay completely flush with the surface. Every screw was aligned so its grove aligned with the airflow.

The wings were made of plywood, for lighter weight. Each was sanded into the perfect shape, then doped (painted) and polished to make its surface smooth as glass.

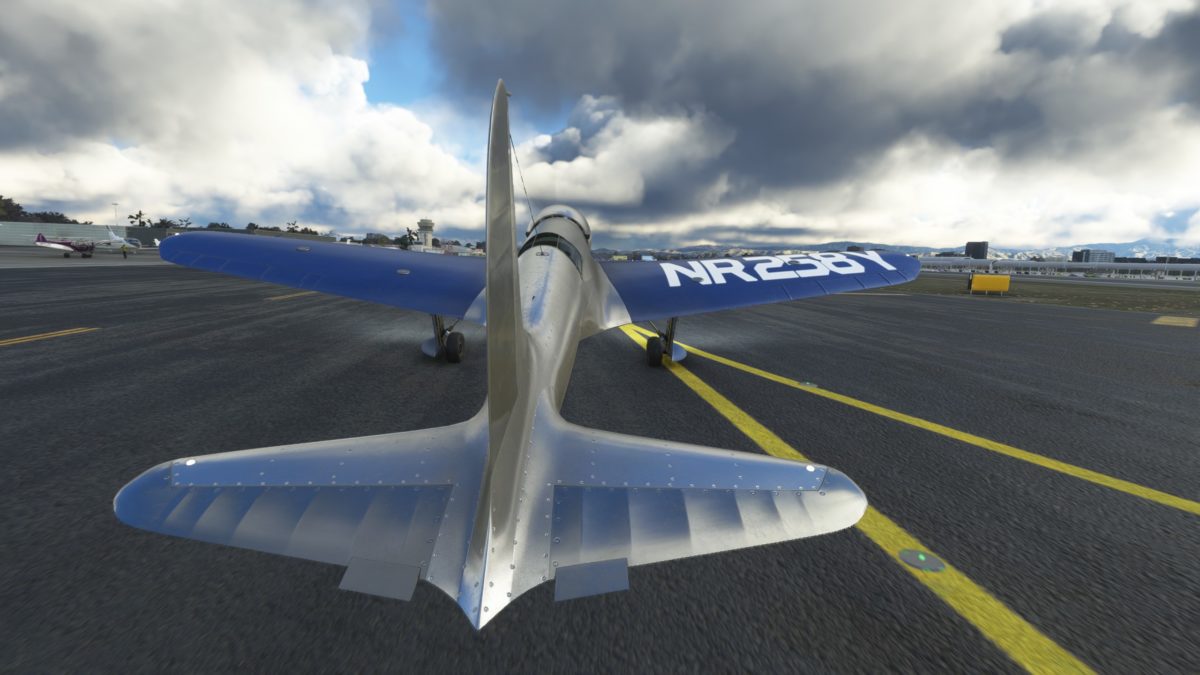

For its initial flights, the wings were quite stubby, giving the H-1 a wingspan of only 24 inches feet 5 inches, compared to a length of 27 feet. This made it challenging to maneuver.

The H-1 featured retractable landing gear, powered by hydraulics. The doors were carefully measured so that when the gear closed, they were completely flush with the underside of the wing.

The H-1 also had flaps to increase lift at slower speeds, on takeoff and landing. While flaps and retractable landing gear were being adopted on airliners like the Boeing 247 and luxury aircraft like the Beechcraft Staggerwing, they were still fairly new innovations.

The H-1’s cockpit reflects the lack of standardized layout typical of that era. Designers were still experimenting to find an optimal arrangement.

On the left side is a crank for the canopy and another crank for elevator trim, as well as switches for magnetos, battery, starter, and lights, plus two fuel selectors.

At the pilot’s left hand is the throttle and mixture. While the pitch of the propeller appears externally adjustable, it does not appear to be controllable in-flight.

On the right side are circuit breakers and a radio. Below it are two levers (one normal, one emergency backup) for raising or lowering the landing gear.

Also on the right are a crank for operating the flaps, and a pull-handle parking brake.

On the left hand of the forward panel are my main flight instruments: clock (left), altimeter (top), vertical speed indicator (below it), and altimeter (below that). At the lefthand center of the panel is a heading indicator.

At the righthand center of the panel is a gyroscopic attitude indicator (artificial horizon). To its right are the main engine gauges, including manifold pressure, RPM, oil pressure, engine temperature, and fuel pressure.

Under the fuel gauges at the bottom center of the panel are my rudder pedals and stick, for controlling the H-1 in flight, as well as a handle for carburetor heat to prevent intake icing.

Under the guiding hand of aeronautical engineer Richard Palmer and production chief Glenn Odekirk (who managed the aircraft fleet for “Hell’s Angels”), the H-1 took shape in a shed in Glendale, California and was ready by August 1935.

The plane had cost Hughes $105,000, equivalent to about $2.3 million today.

On August 17th, Howard Hughes gave the H-1 its first test flight, for a short 15 minutes. His takeoff and landing were filmed here:

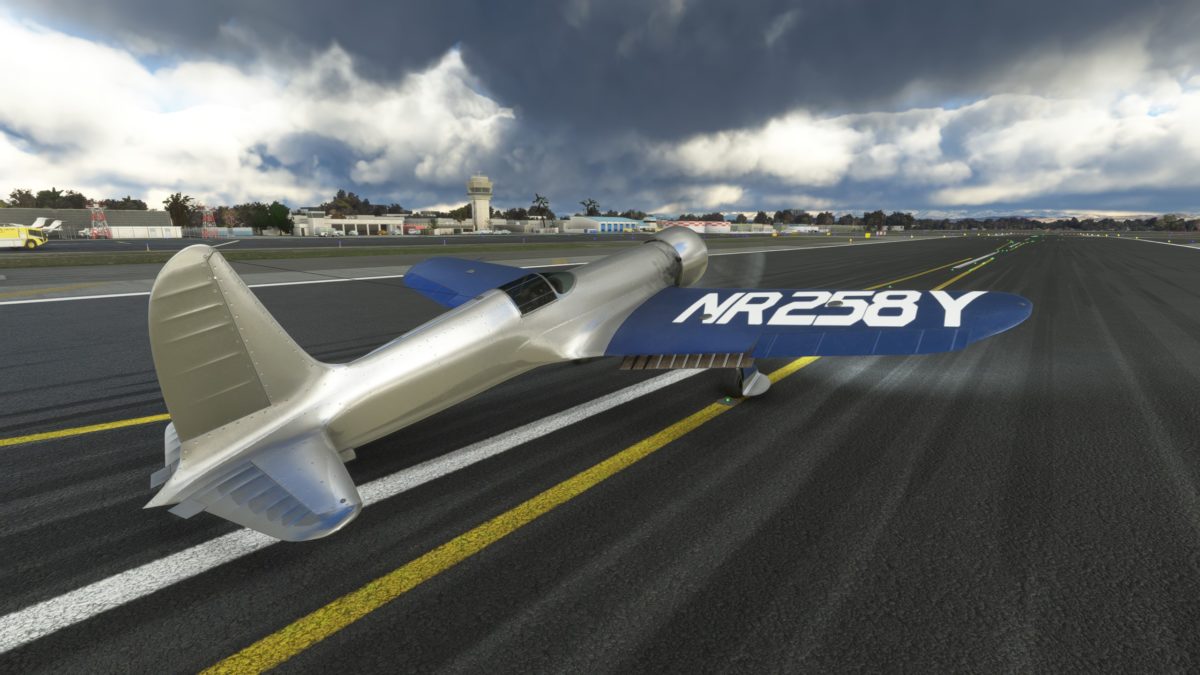

I’m here at the modern-day John Wayne Airport in Santa Ana, California, which is adjacent to the now-vanished dirt airstrip when Hughes and his team gathered a month later to challenge the world landplane speed record.

In an earlier post, I chronicled an earlier attempt by the Gee Bee Model Z at this record in 1931. It clocked an unofficial speed of 315 mph, but a follow-on attempt to make it official ended in a tragic crash.

The standing record that Hughes actually had to beat was 314.32 mph, set the previous Christmas Day by a Caudron C.460, similar to the C.430 I flew in another post.

The first trial on Thursday, September 12 ran too late for the cameras to properly record results . So it was on Friday the 13th that the 29-year-old Hughes – wearing the unusual outfit of “a rumpled dark suit, soiled white shirt, and tie” – took to the air again to challenge the world record.

The rules were as follows: to beat the world record, Hughes would have to make four consecutive passes averaging over 314 mph, at an altitude no higher than 200 feet above sea level. Electronically-timed cameras would – hopefully this time – measure the speed.

Hughes could enter the timed passes in a dive, but from no higher than 1,500 feet. And the plane had to land afterwards with no serious damage.

To get a feel for the plane, I didn’t follow these altitude restrictions precisely, and flew it around a bit.

But on the day of Hughes’ second attempt, famous aviatrix Amelia Earhart flew cover at 1,500 feet to make sure Hughes observed the limit.

If you look at the bottom of the instrument panel, my fuel gauges are half-full. To reduce weight and maximize speed, Hughes took off with just enough fuel to complete seven planned passes.

He posted speeds that day of 355. 339, 351, 340, 350, 354, and 351 mph. The average of the best consecutive four was 352.39 mph, easily beating the previous record.

I made seven passes myself, at full throttle, and repeatedly reached a top airspeed of 310 knots – at which point I could feel the H-1 start to shudder from the turbulence.

At first I couldn’t understand why I couldn’t come close to matching Hughes’ speeds. But then I realized my units were wrong, and that in fact 310 knots equates to over 356 mph. So, mission accomplished.

After his 7th pass, Hughes’ fuel gave out, and the H-1’s engine sputtered to a halt. As onlookers watched in horror, he glided the plane silently to an emergency gear-up belly landing in a nearby beet field.

Except for a few bruises and scrapes, Hughes was uninjured. Despite the crash landing, the plane was considered intact enough to let his new record stand.

Here’s the scene from “The Aviator” showing Hughes’ successful speed record attempt, and the crash landing that followed. (It conflates the first test flight with the speed record run, and gets a few details wrong. The real location was a lot flatter, by intention.)

I haven’t quite run out of fuel, so I have the chance to slow down and try for a safer kind of landing – on the runway. Here I am on the downwind leg of my approach.

The H-1 was flown so few times, there’s no formally-tested approach or stall speed. But I felt it sinking around 100 knots, and figured I better keep it above that, similar to a World War II fighter plane. That must be about right, because I touched down without bouncing.

After Hughes smacked down in the beet field, and was informed he had just set a new world record at 352 mph, his comment was, “It’ll go faster.” He added, “”I don’t see why we can’t use it all the way.”

“All the way” meant a non-stop, long-distance flight from Burbank to Newark, to set a new transcontinental record – beating the one Hughes already held. In January 1937, equipped with longer wings, larger fuel tanks, and an oxygen supply for higher altitudes, the H-1 again took flight.

He crossed the country in 7 hours, 28 minutes and 25 seconds, at an average speed of 332 mph, beating the record set by Roscoe Turner (one of his stunt pilots in “Hell’s Angels) by 36 minutes. He also set new records from Miami to New York and Chicago to Los Angeles.

In July 1938, Hughes went on to fly a Lockheed Model 14, and upgraded version of the L-10 Electra, around the world. He made it in 91 hours (three days, 19 hours, 17 minutes), cutting Wiley Post’s previous record of 186 hours (7 days, 18 hours, 49 minutes) in half.

Howard Hughes was hailed as a national hero. He received the coveted Colliers Trophy, and was hailed with a ticket tape parade in New York City.

Of course, that wasn’t the end of Howard Hughes’ career in aviation. I’ll cover his sponsorship of the Lockheed Constellation and construction of the gigantic H-4 Hercules in other threads.

As for the H-1 Racer, Hughes hoped that the U.S. Army would take an interest in it as a potential fighter plane, but that never materialized.

Later, Hughes claimed that the Japanese had based the design of the Mitsubishi A6M Zero on the H-1. Others speculated that it inspired the German Focke-Wulf 190. But the designers of both planes denied any such influence.

As for the H-1 itself, Hughes kept it around but barely flew it. He sold and bought it back again. Shortly before his death, in 1975, he donated the H-1 to the Smithsonian, where it remains on display today. It has a total of just 40.5 flying hours on it.

In 2003, an aviator from Oregon named Jim Wright built a full-scale flying replica of the H-1 Racer. Sadly, it crashed soon after it was unveiled, killing Wright. It was to have been used in the film “The Aviator”, which ended up using a scale model instead.

Though it is difficult to trace its immediate influence on future aircraft design, the H-1 Racer epitomized many key innovations that were transforming aircraft in lead-up to World War II, and its records set a high bar for future performance.

A wealthy playboy, daring aviator, or eccentric dreamer? Whatever he might have been, Howard Hughes built an impressive machine that, for a time at least, made him the fastest man alive.

Leave a Reply