January 10, 2024

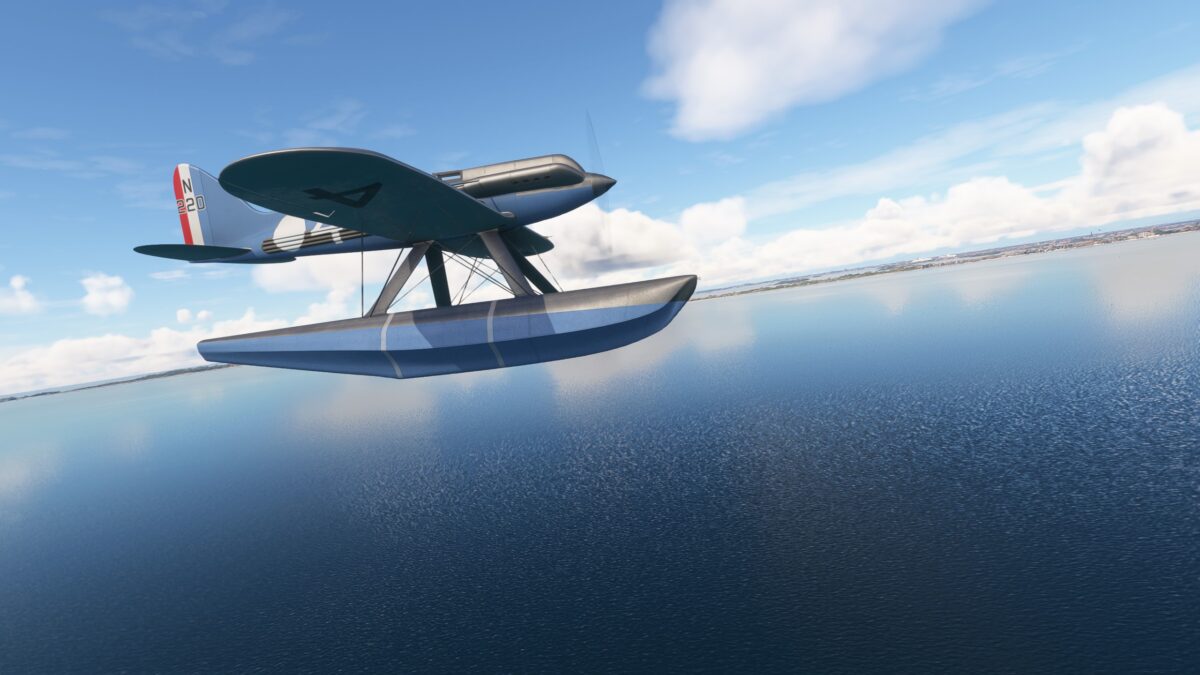

Today in Microsoft Flight Simulator 2020, I’ll be flying the Supermarine S.5, the British racing plane from the 1920s that pointed the way to one of the most iconic planes of World War II: the Spitfire.

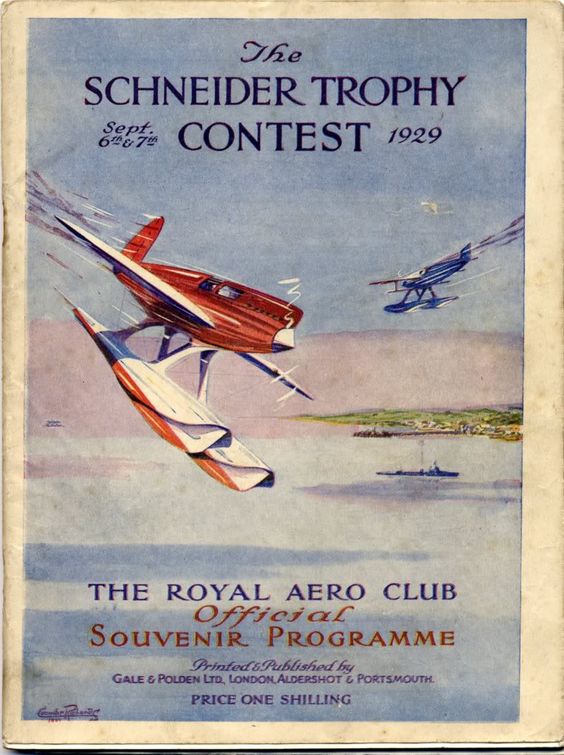

This is also the story of the Schneider Trophy, one of the most prestigious prizes in early aviation, which sparked fierce international competition to develop the fastest planes in the world.

The trophy was the brainchild of Jacques Schneider, a French hydroplane boat racer and balloon pilot who was sidelined by a crash injury. Originally an annual contest, starting in 1912, it promised £1,000 (over $100,000 today) to the seaplane that could complete a 280km (107 mile) course in the fastest time.

Interrupted by World War I, the contest resumed in 1919 with a new provision: any country that won three times in a row would keep the trophy permanently. The prize quickly became the focus of fierce international rivalry.

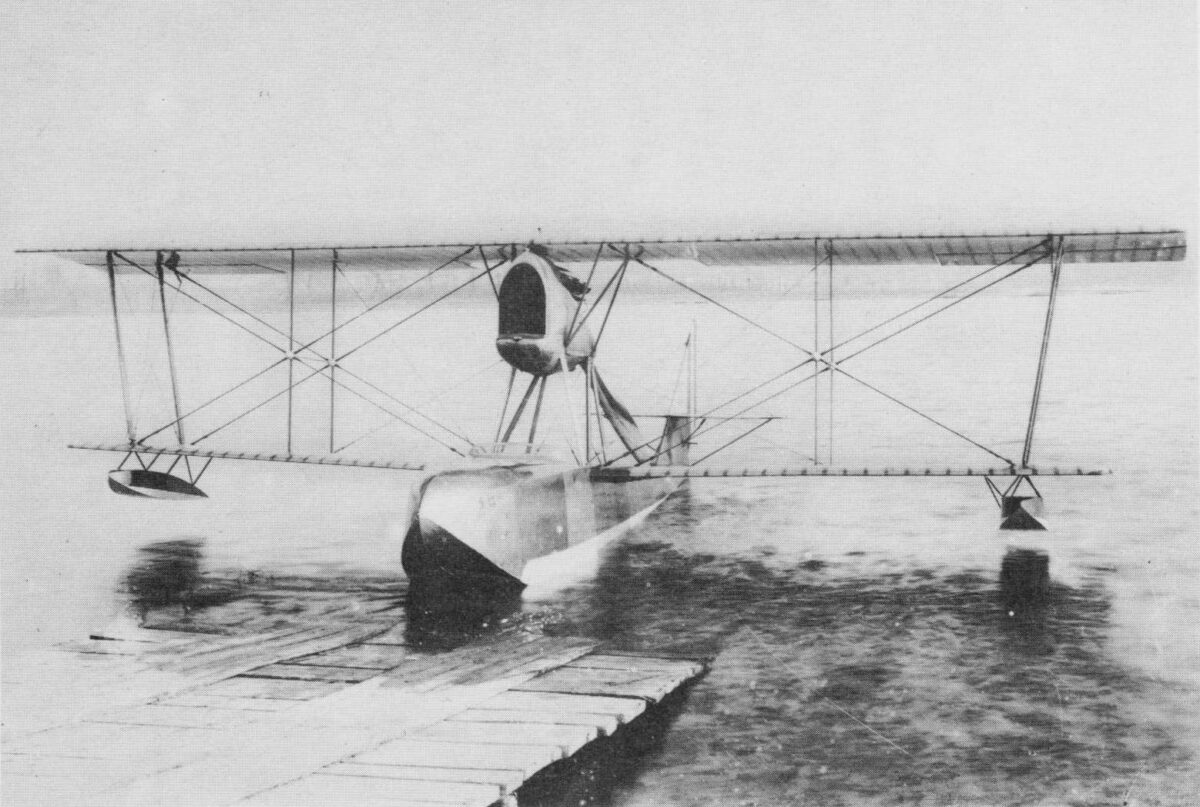

Until 1922, the contest was dominated by flying boats – with their fuselages serving as the floating hull – and by the hard-charging Italians – led by the companies Savoia and Macchi – who came close to walking away with three wins and the trophy, scoring average speeds just over 100 mph.

But starting in 1923, the Americans introduced float planes (streamlined biplanes on pontoons) and took speeds to an entirely new level. Jimmy Doolittle – the famous racer who later led the first bombing raid on Tokyo – won the 1925 race at 232.57 mph, putting the U.S. one step from final victory.

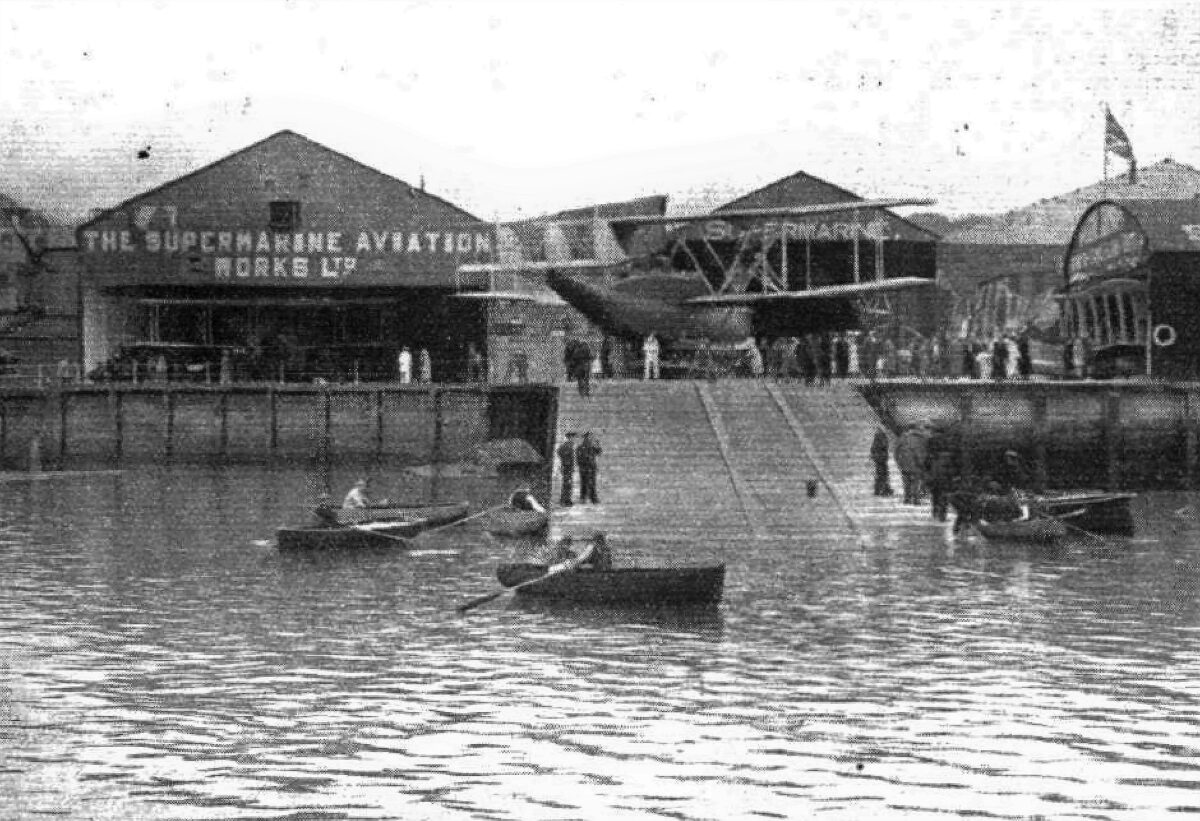

The sole British victory had come in 1922, in a flying boat build by Supermarine Aviation Ltd. Founded in 1913, the Southampton-based company had a disappointing record designing aircraft during the Great War, but since then had enjoyed some limited success ferrying passengers across the English Channel.

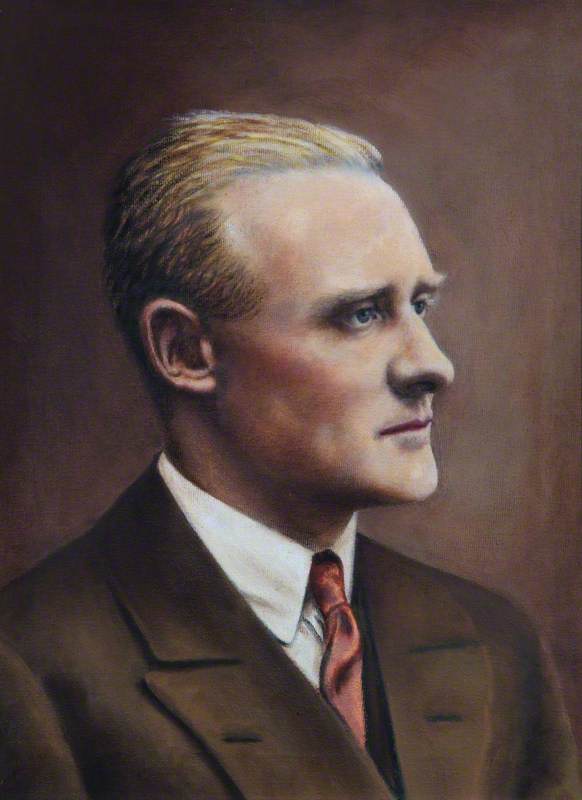

The company’s chief designer was a young man still in his 20s named Reginald Joseph (“R.J.”) Mitchell. Desperate not to be shut out by the Italians and Americans, the British Air Ministry backed his efforts to experiment with some radical new designs.

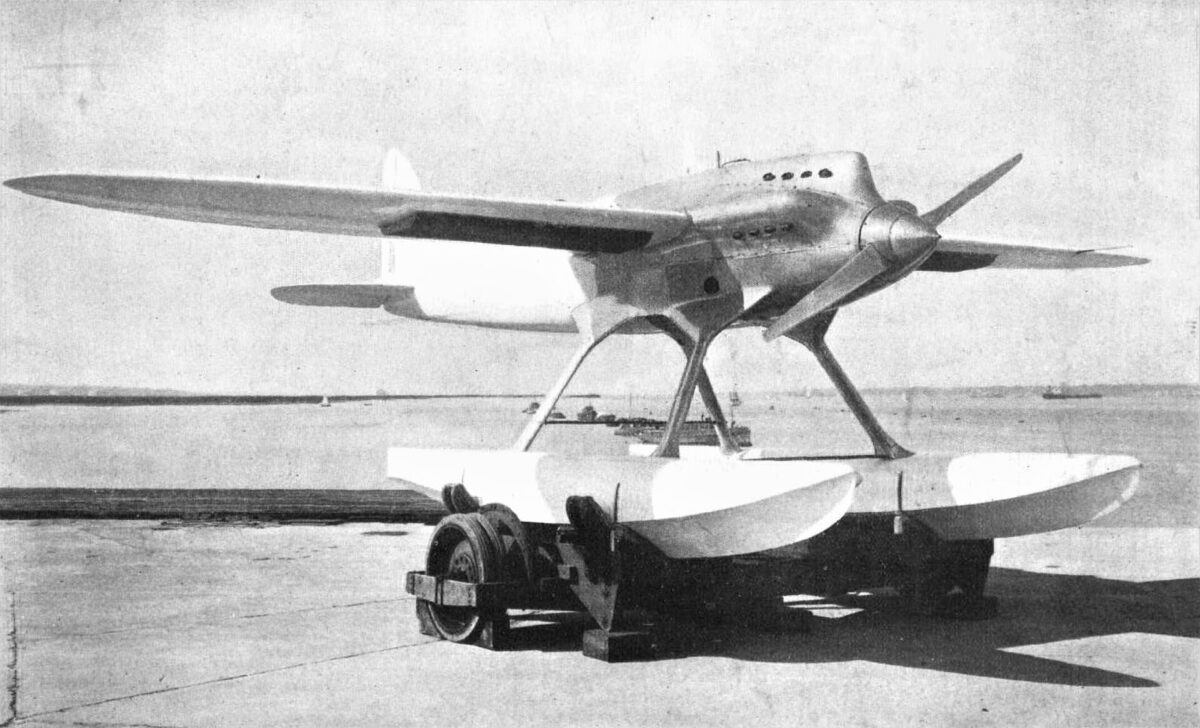

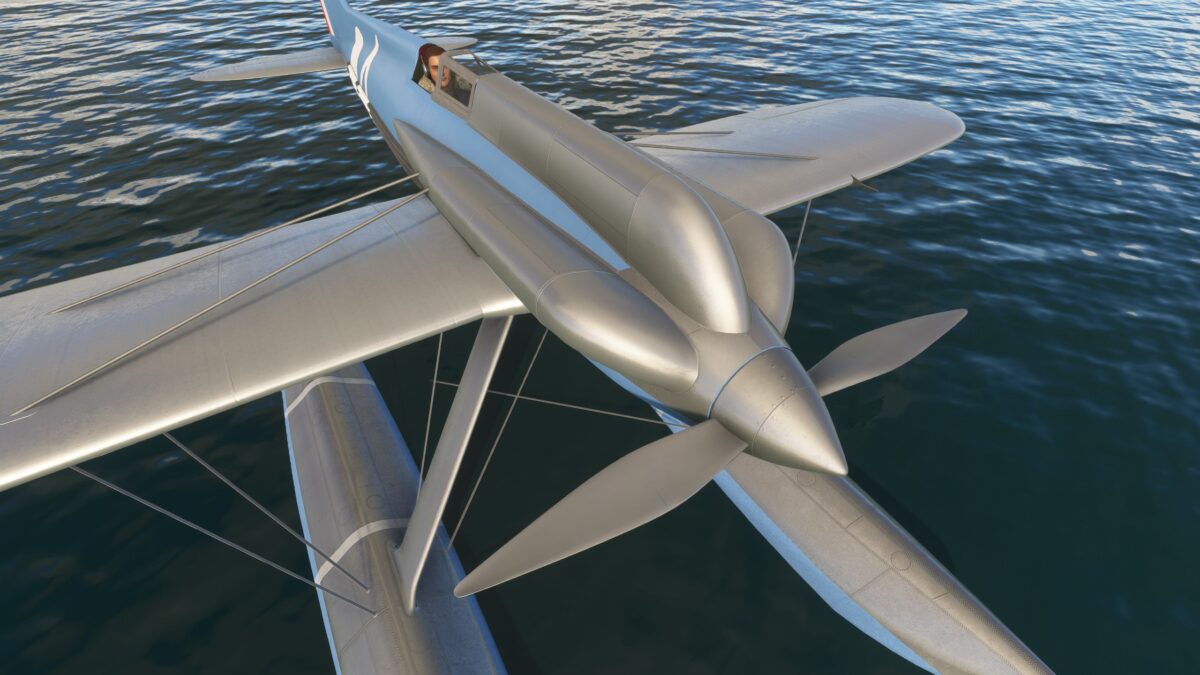

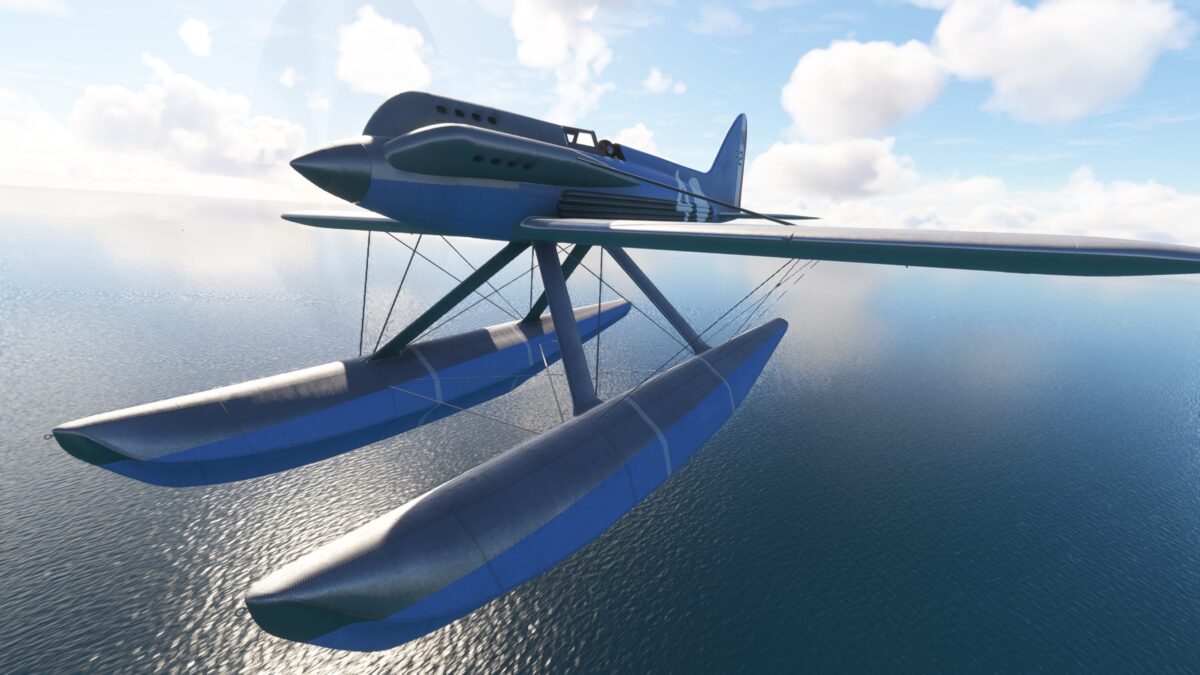

The Supermarine S.4 (S for Schneider) was a streamlined float plane, like the Americans, but a monoplane instead of a biplane, constructed mostly of wood and powered by a 680hp Napier Lion engine. In 1925 it set a world speed record of 226.752 mph, but it proved highly unstable and crashed during trials for the Schneider race that year.

Two years later, in 1927, Supermarine and Mitchell were back with a revised design: the Supermarine S.5. Three were built and entered in the Schneider competition, numbered 219, 220, and 221. I’ll be flying 220 today.

I’ll talk about some of the difference between the S.4 and S.5, but first let’s set the scene. The Schneider Trophy race was hosted by whichever country won the last time. The Italians won in 1926, so the 1927 race was held in Venice.

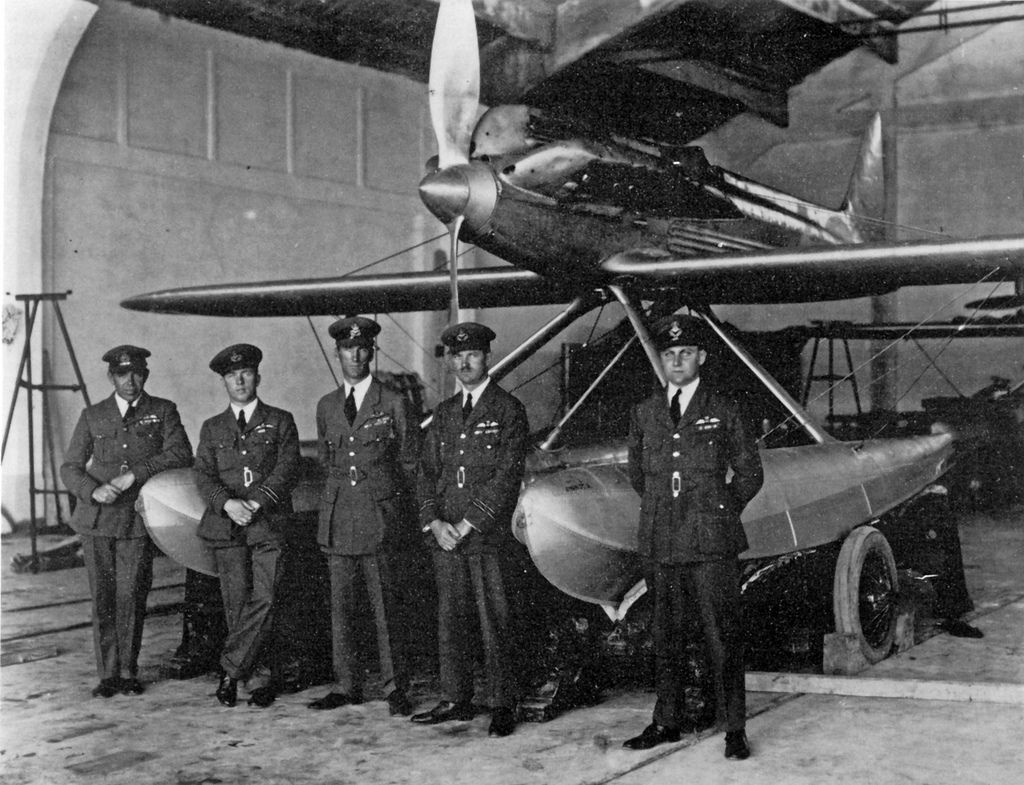

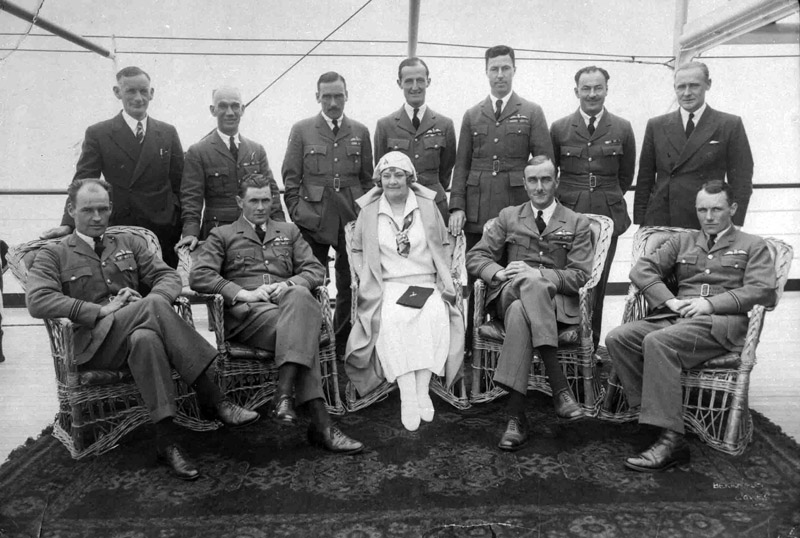

This time, not only was the British government providing financial support, it also sponsored a team of Royal Air Force (RAF) pilots to fly the planes.

One of the more curious conditions of the Schneider contest was that the aircraft first had to prove they were seaworthy by floating for six hours at anchor and traveling 550 yards over water.

I found taxiing, takeoff, and landing quite bouncy – with its powerful engine and high center of gravity, the S.5 had a tendency to porpoise up and down over the smallest waves.

For all the entries, just keeping the fragile airframes together and the high-powered engines functioning was half the battle. Often, the finnicky aircraft broke down or crashed (like the S.4 did in 1925) before they could even begin the race.

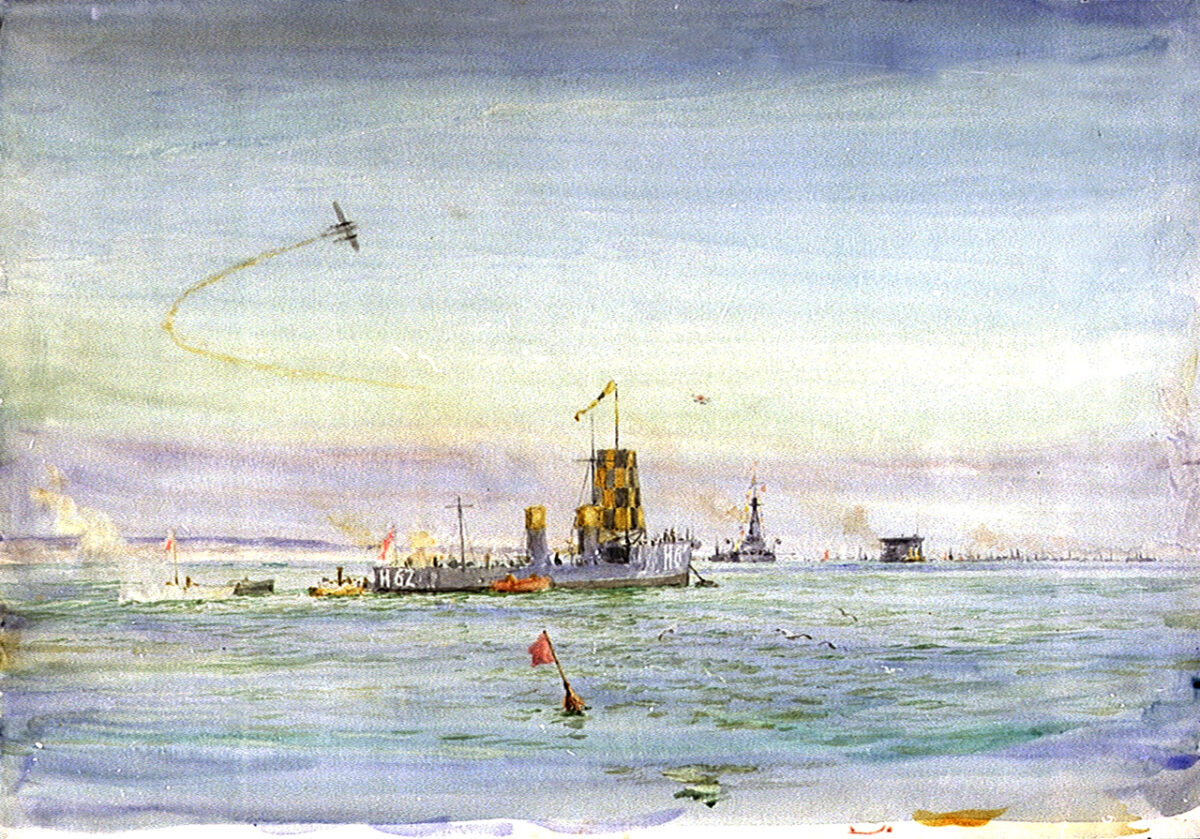

The crowds still came. It’s been barely a few months since Lindbergh crossed the Atlantic, creating a wave of popular enthusiasm for aviation. Over 250,000 spectators have gathered to see the 1927 Schneider race.

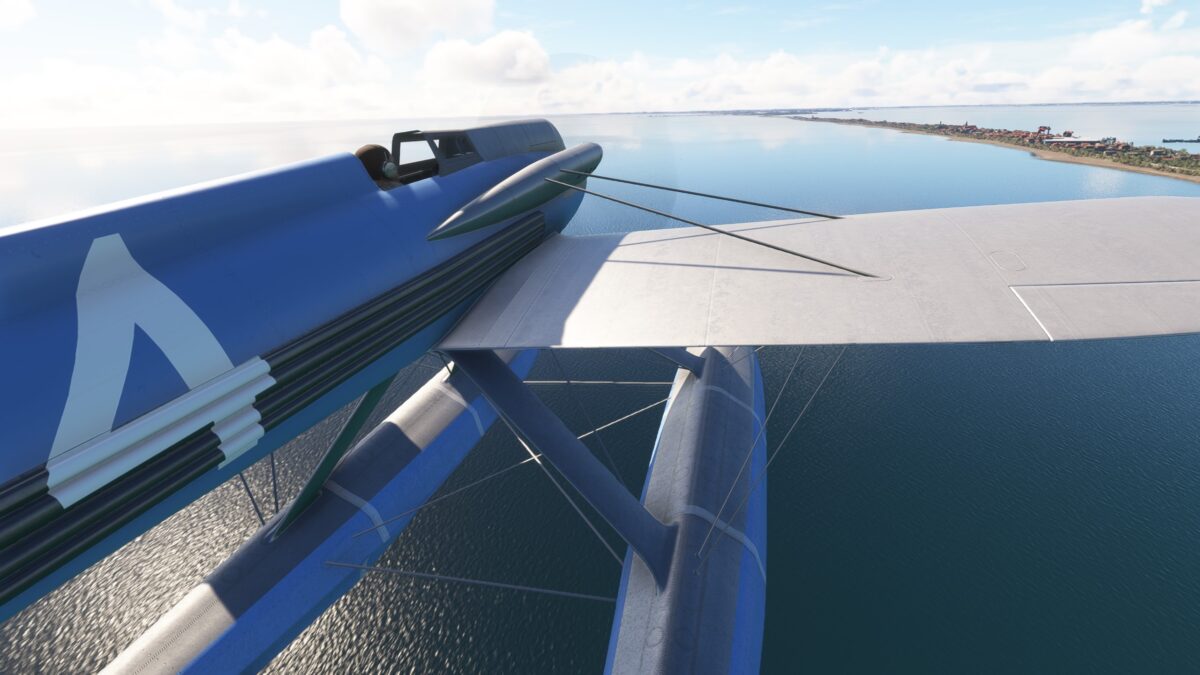

The course itself is located outside the lagoon, along the Lido. The planes must fly seven 47km laps around the course, for a total distance of 320km (just over 204 miles).

And here we go at full speed across the starting line, across from the Hotel Excelsior.

We fly south along the shoreline of the Lido, past the lighthouse at Alberoni, towards Chioggia.

A steep 180-degree turn at Chioggia, a miniature Venice that built its medieval wealth on its adjoining salt pans …

The north on the seaward straightaway …

Another hard left turn around the San Nicolo lighthouse …

Then back across the starting line to begin the next lap.

Here’s a painting of one of the Schneider races, by the English artist William Lionel Wyllie.

Unlike the S.4, the S.5’s wings are strongly braced by wires. These may add unwanted drag, but they keep the plane from breaking up under the stress of those high-speed turns.

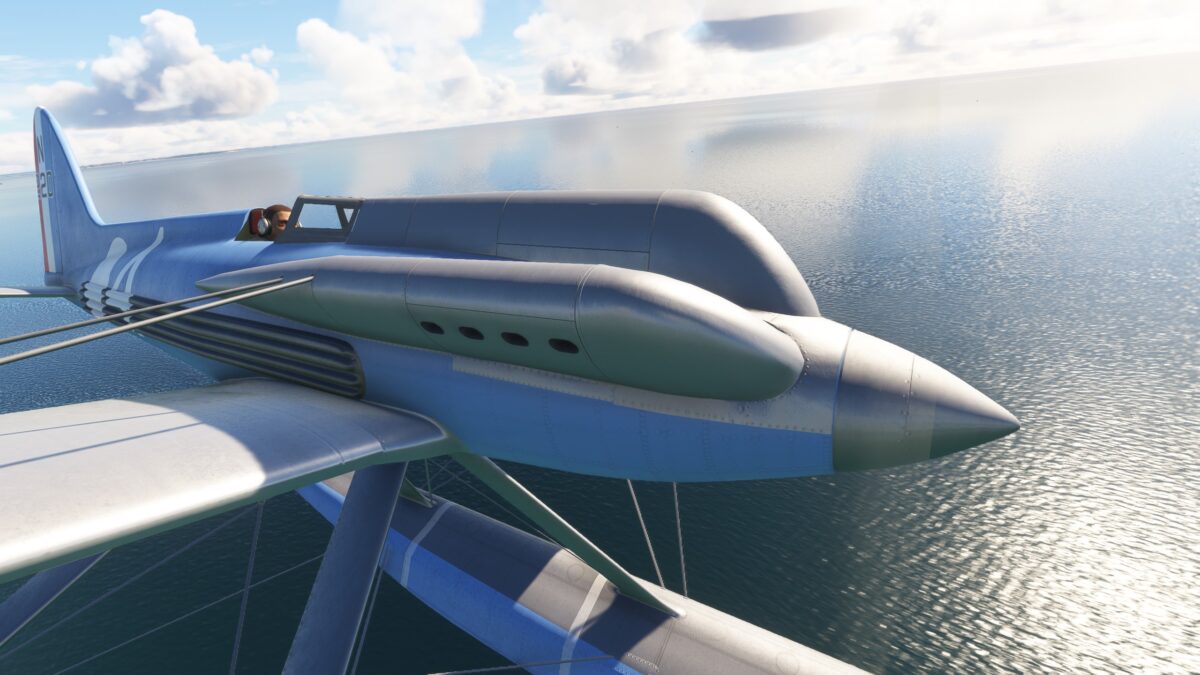

The S.5 I’m flying, #220, is powered by an improved 900hp Napier Lion piston engine, delivering 220hp more than its predecessor. It has 12 cylinders, arranged three lines of four cylinders each, in the shape of a W, creating the three distinct humps along the nose.

The propeller has a fixed pitch. Fuel was carried inside the two floats, while the oil tank was located inside the tail.

The engine was cooled by water which circulated its heat to copper plates on the wings that served as radiators. Corrugated metal plates along the fuselage served as radiators for the engine oil.

The cockpit is mainly designed to monitor if the engine is overheating, and little else. The goal is to keep RPM close to 3300, radiator temperature below 95, and oil temperature below 140.

I’ve found that while the engine may not be air cooled, the flow of air over the radiator surfaces matters a lot. So maintaining a relatively high speed at an efficient engine setting actually helps keep things cool.

There’s an airspeed indicator, but it tops out at 400km/hour, well below our racing speed. There’s no altimeter, and only a rudimentary inclinometer (bubble level) to indicate bank. It’s also nearly impossible to see straight forward over the engine cowling.

In the cockpit, to my right, I have a paper punch card. Every time I pass the finish line, I poke a new hole in it, to keep track of how many laps I’ve completed.

Another little twist in the rules: twice during the race, the aircraft had to “come in contact” with the water – typically a kind of bounce without slowing, which could be very tricky at high speed.

It so happens that in 1927, every single plane except two – both Supermarine S.5s – failed to finish the race for one reason or another.

Our #220, flown by Flight Lieutenant Sidney Webster, came in first with an average speed of 281.66 mph.

The British had won the trophy, but they’d have to repeat their performance two more times to keep it for good. To allow more time for aircraft development, participants agreed to hold future competitions every TWO years, with the next race in 1929.

The contest would take place in Supermarine’s home waters, off Southampton. The company entered one S.5 and two S.6s. The latter, which had roughly the same design, were now all-metal planes with a new engine with more TWICE the horsepower: the 1,900hp Rolls Royce R.

To keep this monster engine cool, the S.6 needed surface radiators built into its pontoons as well as its wings.

Not only did one of the S.6s win the 1929 trophy with an average speed of 328.64 mph, just before the race it set a new world speed record of 357.7 mph.

The British were now one win away from keeping the trophy for good. But with the onset of the Great Depression, the Labour-led British government pulled its funding and forbade RAF pilots to fly in the next race in 1931.

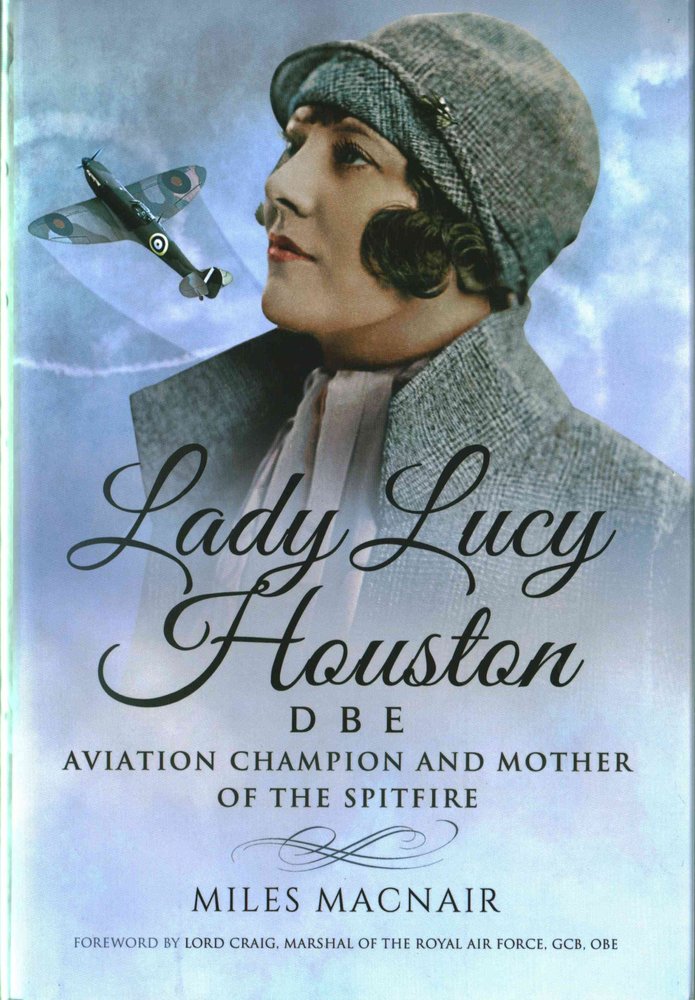

The decision was wildly unpopular, and led to a public outcry. Into the fray stepped Lady Lucy Houston, a former suffragette and the second richest woman in England. Fiercely critical of the Labour Party, she personally pledged to donate whatever funding was needed for Britain to compete in the race.

Backed by £100,000 from Lady Houston (and renewed participation by an embarrassed British government), Supermarine entered six aircraft in the race: two S.5s (including #220 which won at Venice), two S.6s, and two brand new S.6Bs.

The S.6B had redesigned floats, but most importantly, an improved Rolls Royce R engine that delivered an astounding 2,350hp.

As it turned out, no other countries entered the competition that year. The S.6B raced alone, achieving an average speed of 340.08 mph. The next day, the S.6B set a new world speed record of 407.5 mph.

There would be no more Schneider Trophy races. With three wins in a row, the trophy was Britain’s to keep, and today it remains on display at the Science Museum in London, though few visitors may appreciate what it means.

What did it mean? Besides a boost to national pride, the Schneider races propelled aviation forward by leaps and bounds. Today, it might be surprising to realize that the world speed record was consistently held by seaplanes from 1927 to 1935, when the Hughes Racer finally surpassed them.

The Supermarine S-planes, in particular, gave R.J. Mitchell the experience and confidence with incorporating all-metal construction, streamlined monoplane design, innovative wing shapes, and high-performance, liquid-cooled engines.

And the S.6s introduced him to working with Rolls Royce, which built on the lessons learned from its “R” engine to develop a new mass-production engine, starting at 1,000hp, called the Merlin.

In the early 1930s, R.J. Mitchell would marry these proven high-speed design ideas to the Merlin engine to create the Supermarine Spitfire, the legendary aircraft crediting with winning the Battle of Britain.

As for Lady Houston, who supported Supermarine’s entry in the final race, she was later lauded as the “Mother of the Spitfire”, for keeping Mitchell’s development efforts alive.

In 1942, the British produced a wartime movie called “The First of the Few”. It tells the story of Mitchell’s development of the Spitfire, including the key role of the Schneider Trophy races. You can watch the whole thing for free on YouTube here:

But the race planes themselves were mostly abandoned and ultimately scrapped. Only the Supermarine S.6B that won the 1931 race still survives, on display at the Solent Sky Museum in Southampton.

In 1975, Ray Hilborne built a replica of the Supermarine S.5, which was damaged a few years later. A man named Bob Hosie rebuilt it to fly again, inspiring this folk song by Archie Fisher. Sadly, Hosie was killed in 1987 when it crashed.

Today his son William Hosie is part of a project to build a new replica of the Supermarine S.5, which they hope to have flying by 2027. You can learn more about it here: The Supermarine Project (supermarineseaplane.co.uk)

In the meantime, the Schneider Trophy race has been revived, starting in 1981. Instead of seaplanes, it features small general aviation airplanes, as part of the annual British Air Racing Championship.

I hope you enjoyed the story of the Supermarine S.5 and the amazing legacy it left behind.

Leave a Reply