May 30, 2019

From May 30, 2019

Here I am flying over the Coral Sea from Brisbane to the Solomon Islands. It was a new kind of war, with planes from each side searching over vast expanses of open ocean to find the enemy’s aircraft carriers and strike them first.

The US Navy did stop the Japanese invasion fleet aimed at Port Moresby, in the Battle of the Coral Sea in May 1942, but at a high cost: the USS Lexington, one of only a handful of big carriers the US had, was sunk.

Its companion, the USS Yorktown, was severely damaged and was only just repaired to participate with the Hornet and Enterprise in the decisive Battle of Midway (northwest of Hawaii) in June, where four Japanese carriers were sunk.

In the lead-up to the Battle of the Coral Sea, a small Japanese force occupied Tulagi, the tiny capital of the British protectorate in the Solomon Islands, just north of the larger but sparsely inhabited island of Guadalcanal.

When the Japanese invaded these islands, the British officials and their local constables went into hiding, where they served as scouts or “coast watchers” who secretly radio-ed reports of Japanese movements back to the Allies.

Across from Tulagi on Guadalcanal, the British administrator Martin Clemens and his team of local scouts reported that the Japanese had begin building an airstrip on the island.

This tiny airstrip on Guadalcanal alarmed war planners in Washington, DC, because it could potentially extend Japanese air power to threaten the main maritime supply routes linking the US to Australia.

And Australia was where US General Douglas MacArthur, recently escaped from the Philippines, was holed up in this hotel in Brisbane hoping to (eventually) lead the big US Army offensive to take back Asia from the Japanese. (Recall his famous declaration: “I shall return”).

Something I had wondered: why did the Japanese build an airstrip on Guadalcanal, not the British colonial “capital” of Tulagi? Because while Tulagi (pictured here) has a big harbor, the land around it is hilly. There’s no flat land to easily build an airfield.

Whereas across the channel, the northern edge of sparsely inhabited Guadalcanal has the largest plain in the Solomon Islands. Great place to build an airfield – and why that airfield (pic taken from my plane) is still the country’s main international airport today.

So in July, US naval forces spread thinly across the South Pacific – including Marines recently arrived in New Zealand – to make emergency plans to seize Tulagi and Guadalcanal. The preparations were scraped together so fast the Navy called it Operation Shoestring.

It’s easy to forget, but up to that time, the main Allied experience with amphibious landings was the failed British landings at Gallipoli (in Turkey) in World War I. So there was a lot of concern that amphibious assaults were impractical and a recipe for disaster.

There were other problems as well. The top theater commander in the South Pacific, Vice Admiral Robert Ghormley, was an experienced naval diplomat and trusted friend of top Pacific commander Admiral Nimitz, but he was not a “hands on” or particularly assertive leader.

The commander of the naval expeditionary force, Vice Admiral Frank Fletcher, was terrified of losing the few remaining US aircraft carriers entrusted to his care, and faced major fuel shortages that limited his operations.

The naval commander of the amphibious landing force, Rear Admiral Richmond Turner (left), and the Marines commander, General Alexander Vandegrift (right), were more determined, but knew they would quickly be left on their own, once the landings had taken place.

One more thing: the US was publicly committed to a Germany-first strategy. The priority was for men and material towards the planned Allied landings in North Africa, and the Pacific Theater would just have to make do.

So on August 7, 1942, in Operation Watchtower, a force of about 14,000 US Marines slipped around Guadalcanal to the west – undetected by the Japanese – and landed on both Tulagi and Guadalcanal in the first US ground offensive of the war.

About 11,000 Marines landed with little opposition on Guadalcanal and quickly captured the airfield, as the small Japanese force building it fell back inland into the jungle.

The anti-climactic nature of the landings on Guadalcanal were captured in the first episode of “The Pacific”, here:

And here’s me making a similar approach to Guadalcanal (coming back from Tulagi) just the other day:

The biggest problem the Marines had upon landing on Guadalcanal was coping with the massive amount of supplies that needed to be unloaded, quickly, before the transport ships had to leave. They were completely unprepared, and it just piled up on the beach.

The 3,000 US Marines who landed on Tulagi got a much hotter reception. The Marines landed on Blue Beach and swept south, but by sunset found themselves held up by Japanese dug in deep on Hill 281.

Students studying and playing on Blue Beach, where the US Marines came ashore on Tulagi on August 7, 1942.

Blue Beach later served as the location of the US Marines’ hospital on Tulagi. It’s now been replaced by an elementary and middles school donated by a US Marine Corps veterans association.

Signs painted on the nearby cliffs at that time, and still clearly visible, show where vehicles were to be parked at the US Marines hospital on Tulagi’s Blue Beach.

Schoolboys waging a mock battle of “capture the fort” on Blue Beach, where US Marines landed on Tulagi on August 7, 1942.

The cliffs facing Blue Beach on Tulagi are steep, and the Marines had to battle uphill to secure the island’s high ground.

One of many concealed tunnels on Tulagi, from which the small number of Japanese troops on the island fought back fiercely against the arriving US Marines.

The view from inside the tunnel.

The concrete base for a US flagpole on Tulagi, constructed a year later when the island was securely in Allied hands.

The foundations of the British Commissioner’s Residence on Tulagi, on the high ground captured by the US Marines on the first day they landed on the island.

Looking south at Hill 281, the last hold-out of the Japanese, from the British Commissioner’s Residence on Tulagi. This was the front line at sunset on the first day the US Marines landed, where the Japanese made several “banzai” charges that night.

Behind it (same photo) across the bay you can see the small islands of Tanambogo and Gavutu, which were also Japanese strongpoints which held out fiercely against landings that day by the Marines.

It took three days of vicious fighting, including barrages of artillery and dive-bombing at suicidally close range, to kill all the Japanese dug into Tanambogo (right) and Gavutu (left). Hardly any defenders surrendered.

US Marine Corps Sergeant Frank McCulloch, who was not at the battle, later memorialized the Marines who fight and died in the battle on Gavutu.

Brigadier General Rupertus (center) supervising the US Marines assaults on Tulagi, Gavutu, and Tanambogo from his command ship in August 1942.

US Marine officers commanding the units that assaulted Tulagi pose for a group photo shortly after the battle. By August 8, Hill 281 had been captured and the island secured. 307 Japanese and 45 US troops died. Three Japanese soldiers were taken prisoner.

The Raiders Hotel and Bar, where I landed on Tulagi, is named in honor of two special Marines commando units, one led by Lt. Col. Merritt Edson, which played a key role in the capture of Tulagi – and which we’ll meet again on Guadalcanal.

On their wall, they have a map that gives you a better sense of the layout of Tulagi, its harbor, and the islets of Tanambogo and Gavutu.

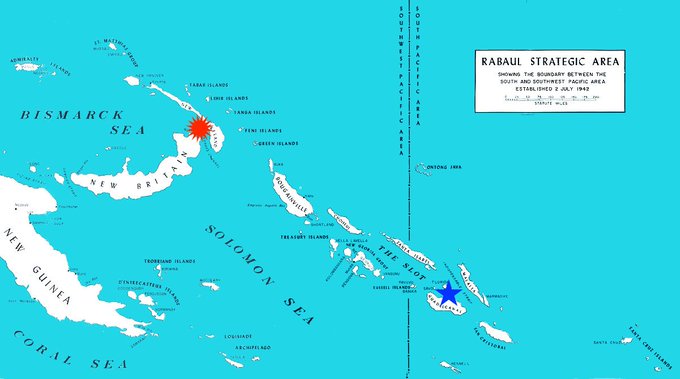

The closest Japanese naval and air base to the US landings on Guadalcanal and Tulagi (blue star) was Rabaul (red sun). Its bombers and fighters could just reach Guadalcanal at the end of their striking range.

Which is what they did. Here are Japanese G4M “Betty” bombers making a torpedo run on US transports off Guadalcanal on August 8, the day after the US landing. They took heavy losses but sank one US transport ship.

Spooked by these air raids, Admiral Fletcher announced he was withdrawing his aircraft carriers immediately. Admiral Turner and his small fleet of cruisers and destroyers would stick around to try to finish offloading his transports, without any air coverage.

The Americans didn’t know it, but immediately on hearing news of their landing, Vice Admiral Gunichi Mikawa sent a force of seven cruisers and one destroyer steaming from Rabaul down the channel called “The Slot” to hit the US invasion fleet.

Unaware the Japanese were coming, Admiral Turner put out his cruisers and destroyers as pickets to protect the approaches to the vulnerable transports, which were still unloading. But only on half-alert.

As the sun set on August 8, they were posted on either side (left and right) of Savo Island, a volcanic outcrop known as “the round mound in the sound”, seen here looking west from near the US Marines perimeter on Guadalcanal.

The Japanese had trained intensively in night fighting. A few US ships had radar, but were new at using it, and were caught completely by surprise.

First the Japanese swung south, blew the bow off the cruiser USS Chicago, and set the Australian cruiser HMAS Canberra on fire.

View from the Japanese cruiser Chokai as aerial flares illuminate the Allied southern group of ships during the Battle of Savo Island.

Then, without any alarm being raised, the Japanese swung north to hit the northern pickets. Three US cruisers, the Quincy, Vincennes, and Astoria, were all sunk.

The Japanese cruiser Yūbari shining searchlights towards the northern force of US warships during the Battle of Savo Island.

Last photo of the cruiser USS Quincy, on fire and illuminated by searchlights from attacking Japanese ships, during the Battle of Savo Island.

As this clip from “The Pacific” shows, US Marines on Guadalcanal could easily see the ships slugging it out and catching fire. They hoped it was the Japanese fleet catching hell. In fact, it was their own US warships being blown up before their eyes.

Admiral Mikawa now had a choice: attack the US transports and risk being exposed to US carrier-based planes at sunrise, or leave now, almost completely unscathed. He chose the latter. He didn’t know that the US carriers were already departing the area.

But the Battle of Savo Island would still go down as one of the worst defeats suffered in the US Navy’s history. Four Allied cruisers were sunk and others severely damaged. 1,077 Allied sailors lost their lives.

Japanese artwork from during the war depicts the Battle of Savo Island, a resounding nighttime victory for the Imperial Japanese Navy off Guadalcanal.

US destroyers rescuing Australian sailors from the burning HMAS Canberra, which sank soon afterwards, the morning after the Battle of Savo Island.

Australian cruiser HMAS Canberra sinking after the Battle of Savo Island, off Guadalcanal.

With that, Admiral Turner decided to stop offloading supplies and get his transport ships out of there immediately, leaving the US Marines now sitting on Guadalcanal to their fate …

The Marines now worked diligently to finish the airstrip on Guadalcanal that was started by the Japanese. They named it Henderson Field after a US aviator killed in the Battle of Midway, a few months before.

Henderson Field is now the international airport for Honiara, the new capital of the Solomon Islands that was founded after the war. It’s where I arrived on Guadalcanal.

The arrival and departure areas at Henderson Field, modest as they may be, don’t let you forget the heritage of this unique airport.

Henderson Field opened for business on August 20, 1942, with the arrival of one squadron each of 19 F4F Wildcat fighters (pictured here) and 16 SBD Dauntless dive-bombers.

These were later augmented and (when bombed or shot down) replaced by a hodgepodge of Army, Navy, and Marine aircraft that came to be known as the Cactus Air Force (Cactus was the codename for Guadalcanal).

Henderson Field was both the reason the US Marines were on Guadalcanal, in the first place, and the key to their defense, by providing invaluable air cover.

Constantly strafed, shelled, and bombed, the Cactus Air Force at Henderson was always in the constant process of being patched back together, salvaging parts and scarce fuel from one plane to make sure another could fly.

Soon the Seabees (naval construction units) were brought in to lay down a metal grating for the airstrip and taxiways. Some of it’s still lying around.

Today, some of the old metal airstrip grating from the war has been repurposed as housing material along the outskirts of Henderson Field.

As long as Henderson Field and the Cactus Air Force were in operation, it meant that US forces controlled the sea lanes around Guadalcanal during daylight, and were able to (piecemeal) bring in reinforcements and supplies.

That is, with the exception of Japanese submarines lurking in the approaches south of Guadalcanal, at what was dubbed The Junction. When Marines could hear the explosion of torpedoes from these attacks, they would murmur that “there’s a function at the junction.”

But when night came, the Cactus Air Force was blind, and the Japanese sent convoys of fast destroyers dubbed “The Tokyo Express” down “The Slot” to reinforce and resupply their forces on Guadalcanal, and even shell the airfield, and get away under cover of darkness.

The Marines’ perimeter around Henderson Field wasn’t that large. In the distance, on the right, you can see Mount Austen aka “the grassy knoll” which was held by the Japanese and offered excellent views of everything happening in and around the US airstrip.

Admiral Yamamoto, the author of the attack on Pearl Harbor, didn’t really care about retaking Guadalcanal, for its own sake. But he believed the Americans did care, and that pressure on Guadalcanal could be used to lure the remaining US carriers into battle.

So the Tokyo Express began landing an elite unit led by Colonel Kiyonao Ichiki (who helped stage the “Marco Polo Bridge Incident” in 1937 that triggered Japan’s invasion of China), along the coast east of the US Marines perimeter.

Ichiki was a real firebrand whose past victories caused him to underestimate his enemy. He didn’t even wait for his whole unit to show up before launching an attack on the US Marines, who he was confident would be swept away by Japanese valor.

On August 20, Ichiki’s forces captured a local native Coastwatcher named Jacob Vouza scouting for the Americans east of the US perimeter. The Japanese tied him to a tree, tortured him, and – when he wouldn’t talk – stabbed him in the neck to finish him off.

But amazingly, Vouza wasn’t dead. When the Japanese left, he untied himself and somehow lurched back to American lines to inform them of Ichiki’s impending attack. He recovered and continued serving thru the campaign. Vouza was later knighted and remains a huge local hero.

The Marines now knew where the Japanese attack was coming, from the east, along Alligator Creek (which they mistakenly thought was the Tenaru River) – and they dug in accordingly.

The banks of Alligator Creek today, just east of Henderson Field, are covered with 2nd-growth forest. At that time, both banks hosted coconut groves, part of a plantation owned by Lever Brothers. The Americans held the left (west) bank, the Japanese attacked from the right.

Here’s Alligator Creek looking in the other direction (south). The US Marines were dug in with machine guns on the right (west), amid the coconut palms.

This isn’t Alligator Creek, it’s another river further west, but it gives you an idea of the sandbar that spanned the mouth of the creek, across which the Japanese led a nighttime “banzai” attack.

The misnamed Battle of the Tenaru is depicted in this clip from “The Pacific”, which gives an accurate depiction of the nighttime attack by 800 elite Japanese troops against the dug-in and ready US Marines, across Alligator Creek.

By the way, the character “Lucky” in “The Pacific” series is Robert Leckie, who later went on to become an author and historian, and whose book on Guadalcanal is well worth a read:

The result was a horrific Japanese defeat. Ichiki and his unit, confident their charge would sweep all before it, were wiped out nearly to the man.

This clip from “The Pacific” accurately shows the aftermath of the battle, along the sandbar at the mouth of Alligator Creek.

It also accurately depicts the dying efforts by wounded Japanese to grenade US medics who came to their aid. This fanaticism had a chilling effect on the Americans. For the rest of the Pacific war, they would rarely take prisoners, even wounded, for fear of falling prey.

Dead Japanese soldiers lying under the coconut palms beside Alligator Creek, after the Battle of the Tenaru on August 21. Many have been run over and chewed up by the treads of advancing US light tanks.

In response to the new Japanese landings and ground attacks on Guadalcanal, Admiral Fletcher brought his three carriers, the USS Saratoga, USS Wasp, and USS Enterprise, farther north to provide air cover for the threatened Marines.

That put them on a collision course with a Japanese carrier task force commanded by Vice Admiral Chūichi Nagumo, cruising north of the Solomon Islands. Just as Admiral Yamamoto had hoped, here was their chance to destroy the precious US aircraft carriers.

The dance began between the opposing sides to locate and launch strikes against each other’s carriers first, in what became known as the Battle of the Eastern Solomons.

The aircraft carrier USS Enterprise throwing up anti-aircraft fire, under attack by Japanese dive-bombers and on fire from an earlier bomb hit. During the Battle of the Eastern Solomons on August 24, 1942.

Japanese Val dive-bomber, being shot down over the USS Enterprise during the Battle of the Eastern Solomons.

Bomb hitting the flight deck of the USS Enterprise during the Battle of the Eastern Solomons.

The Battle of the Eastern Solomons, in late August, was basically a draw. The USS Enterprise was badly damaged, and the US sank one smaller Japanese carrier, sent out as a diversion. Both sides were playing it safe, and withdrew.

Meanwhile, the Tokyo Express nighttime destroyer runs were gradually landing more Japanese troops on Guadalcanal, building up for new attack.

And the carrier USS Saratoga was torpedoed by a Japanese submarine, putting it out of action for the foreseeable future, leaving just two US carriers in the South Pacific.

Because it was often operating beyond the horizon, the U.S. Navy is sometimes blamed for “abandoning” the Marines on Guadalcanal. In fact, it never stopped waging a much broader campaign to prevent Japan from concentrating its forces there, a campaign in which it continued to suffer substantial casualties and inflict substantial damage.

The battle for Guadalcanal is far from over. Click here for Part 2, to continue the story.

Leave a Reply