May 30, 2019

But the battle for the remote Solomon Islands was not over. And no one would experience this more directly than a young man born to privilege who arrived in Tulagi in April 1943, to take command of a PT patrol boat. His name was John F. Kennedy.

This quonset hut on Tulagi was the repair shed for damaged PT boats, which began to be deployed in the waters around Guadalcanal in late 1942.

PT (short for “patrol torpedo”) boats were a glamorous new weapon. Packing torpedoes and depth charges and engines that could propel them at over 40 knots, they were also an opportunity for a relatively junior officer to have his own command.

They had several shortcomings, however. First, their torpedoes often didn’t work – a serious problem that plagued US submarines as well, and which the Navy was in total denial over.

Second, in the daylight the PT boats were sitting ducks for Japanese dive-bombers, which continued to hit Tulagi and Guadalcanal from a new airbase they built at Munda (red circle).

Third, at night in the Solomons, when moving at fast speeds the PT boats gave off phosphorescent wakes, making them nearly as visible – and vulnerable. They had to slow down and maintain radio silence, which made it hard to communicate and coordinate any kind of fast attack.

On the day in April 1943 that Kennedy arrived in Tulagi harbor (pictured here), a Japanese bombing raid came in and nearly sank his transport.

But the US could hit back in the air as well, with the arrival of new planes in the South Pacific Theater like the quick and longer-ranged P-38 Lightning.

In fact, it was a squadron of P-38s that, acting on a decrypted Japanese radio message, was able to ambush and shoot down a plane carrying Admiral Yamamoto (the author of the attack on Pearl Harbor) over the island of Bougainville on April 18, 1943.

Admiral Yamamoto, a few hours before his death, saluting Japanese naval pilots at Rabaul. His death deprived Japan of one of its greatest military strategists.

Back in Tulagi, Kennedy (far right) was assigned command of the PT-109.

Meanwhile, US commanders were drawing up a plan to encircle the Japanese base at Rabaul. Called Operation Cartwheel, its left hook was to be led by troops under General MacArthur driving northeast from New Guinea.

Its right hook would consist a drive northwest from Guadalcanal, including US landings on and around New Georgia to neutralize the Japanese airstrip at Munda.

To get to this theater of operations, I flew to that Japanese airstrip at Munda, now the local airport.

And when I say local airport, well … it’s a pretty modest affair.

The town of Munda is basically about two blocks long, with the airport on the inland side and an informal marketplace by the shore. Like in most parts of the Solomon Islands, the town’s 3 or 4 general stores are all run by migrants from China.

The roads give out soon beyond the town’s edge, so boats serve as the local buses.

Before Christian missionaries arrived in 1909, the area around Munda was known for headhunting. After most villages converted, some holdout warriors repaired to the isolated islands of the nearby Vonavona Lagoon.

They brought their collection of skulls to what is now called “Skull Island”, about half an hour off Munda.

A metal bowl on Skull Island in Vonavona Lagoon used for rituals to swirl the water they contain and call up storms. Best not to touch.

The skulls kept on Skull Island consist of both slain enemies and revered relations, mixed together.

The most powerful skulls are kept in this special stone hut. The skull on the upper right belonged to a renowned warrior chief who relocated to the Vonavona Lagoon after the Christian missionaries arrived.

Next to the skulls is an altar to the Fish God (whose totem is in the center), where people could come and pray for successful fishing.

The Christian descendants of the headhunting chief are still buried on Skull Island in Vonavona Lagoon.

My boat back to Munda, tied up on Skull Island.

From Munda, you can see the peaks of Rendova Island, across the channel to the south.

On June 30, 1943, US troops landed on Rendova Island as part of what was dubbed Operation Toenails, in a preliminary to moving on Munda.

And soon afterward, Kennedy’s PT squadron was relocated to a primitive “bush camp” on tiny Lumbaria island, just off Rendova. From my plane window, it’s the island I’ve circled in white.

The first part of the crossing from Munda to Kennedy’s PT base near Rendova, inside the coral reef, was smooth as glass.

On the horizon, the surf line is like a clear step in elevation. Once you cross it, and get out into the channel, between Munda and Rendova, the ride is a lot bouncier. These are the waters the squadron of PT boats Kennedy belonged to would have patrolled, usually at night.

The American PT base at Lumbaria island may look like a tropical paradise, but it was tiny, primitive, and rife with tropical diseases. The shallow waters protected it from Japanese destroyers, but it was subject to bombing raids from Japanese aircraft in the vicinity.

There’s a local family that lives on the island and looks after the old PT base. They don’t get that many visitors and were especially excited when they learned I’m an American.

The base was damaged by the tsunami that hit the Solomon Islands in 2007. Many relics were lost or stolen in the aftermath.

They’ve reconstructed a hut over the concrete base of the original mess (left), and are building a “museum” over the concrete base of the officers’ quarters that Kennedy shared (right).

Yep, future President John F. Kennedy may have drank one of these Coca-Colas in the mess of his PT base on Lumbaria Island.

Here’s the remains of the bunker where they took shelter during Japanese air raids.

They had a bakery (bottom left) and a fresh-water well (behind it), but things were pretty spartan.

When I first arrived, the little monument they have to Kennedy’s memory was bare. “We didn’t know you were coming!” But the family rushed back to their huts and got out all the gear and set it up for me.

They really have carved quite a respectable looking bust of JFK out of local wood!

The man who looks after the PT base hopes that someone from the Kennedy family will come someday to visit. He also hopes to set up a small cabin for visiting tourists to stay overnight.

His family was shy but very welcoming. His daughter (second from left) is studying in the Philippines to become a nurse.

As we waved goodbye, I thanked them for preserving a piece of my own country’s history, in such a distant land.

Back at my quay-side lodgings at Munda, I was reminded more than a little of another famous PT boat base in the South Pacific: the one in the TV sitcom “McHale’s Navy”.

The original pilot for “McHale’s Navy” was actually an action drama that aired in 1962, starring Ernest Borgnine (a WW2 navy veteran) as a captain of PT boat who is stranded, with a handful of survivors, on a remote island base (like Lumbaria Island) after a Japanese attack.

It was, of course, recast as a comedy series featuring McHale (Borgnine) as the captain of a misfit PT boat crew defying Navy rules to enjoy themselves in the tropics.

It’s actually pretty fun, in the context of this thread, to go and watch the first full comedy episode of the series.

McHale and his crew are supposedly based on “Taratupa”, which sounds like Tulagi and looks a lot like what the base there probably looked like (quonset huts and all). At one point, his CO points on the map to southern New Zealand as their location, which is ridiculous.

But look at the map that’s actually behind them on the wall in the CO’s hut in the first episode. Recognize it? That’s Guadalcanal and Tulagi/Florida Islands, with Iron Bottom Sound between them.

By the way, McHale’s martinet commander, Captain Wally Binghamton, bears more than a passing resemblance to the descriptions I’ve read of Kennedy’s PT boat squadron commander. He was not much loved.

On July 2, 1943, US Army troops made their main landing on New Georgia, aimed at capturing Munda. But over the next few days, they found their advance bogged down against determined Japanese defenders.

The Japanese had no intention of giving up New Georgia without a fight. They quickly sent 4,000 troops via the Tokyo Express to Vila on Kolombangara Island, where they would be ferried across Kula Gulf to Bairoko harbor, and then marched by an 8-mile jungle trail to Munda.

I traveled to Bairoko harbor (seen here), where some remnants of that Japanese reinforcement and supply effort remain.

Here I am snorkeling over the wreck of the Kashi Maru, a Japanese freighter that was carrying food and ammo to supply the defenders at Munda. It was sunk in Bairoko harbor by a US air raid on July 2, 1943 – the same day the US Army landed near Munda.

Here are some Japanese coastal artillery guns further north of Bairoko, near the northern tip of New Georgia, looking out over the Kula Gulf.

The vegetation surrounding it gives you a good idea what the fighting environment was like along these “jungle trails” that linked the main Japanese positions on New Georgia.

US soldier fighting in the same environment on New Georgia in August 1943.

On July 5, the US Army landed another force along the Kula Gulf north of Bairoko, aiming to capture that harbor and key Japanese supply link.

Rain clouds over Kula Gulf, looking south towards Bairoko harbor.

On the next night, August 5-6, the covering force of 3 US cruisers and 4 destroyers was sent to intercept the Tokyo Express sending reinforcements to Bairoko, via Kolombangara Island (seen here across Kula Gulf, shrouded in clouds).

Cruisers USS Helena and USS St. Louis in nighttime action against the Tokyo Express in the Battle of Kula Gulf, seen from USS Honolulu.

The cruiser USS Helena – a surviver of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor AND the bloody Night Cruiser Action on November 12-13 off Guadalcanal – was hit by several Japanese torpedos in Kula Gulf and sunk.

Most of the USS Helena’s 900 sailors were rescued right away, but about 275 found themselves adrift, clinging to wreckage, for several days.

Storm cloud over the Kula Gulf, looking north, where USS Helena’s survivors were drifting for days.

This story has a much happier ending than the USS Juneau, however. Most of the survivors ultimately made it ashore, and hid from the Japanese with local help. Nearly all of them were eventually rescued successfully.

The wreck of the USS Helena was recently discovered in Kula Gulf, in March 2018.

The naval battle to stop the Tokyo Express (fast Japanese destroyers) from reinforcing New Georgia involved repeatedly clashes. The cruiser USS St. Louis later got its bow blown off by a Japanese torpedo at the Battle of Kolombangara on July 13.

The cruisers USS St. Louis and HMNZS Leander intercepting the Tokyo Express at the Battle of Kolombangara, also known as the Second Battle of Kula Gulf, on July 13, 1943.

All of which leads to the inadvertently most famous incident of the New Georgia campaign … the sinking of John F. Kennedy’s tiny PT-109 , and the crew’s struggle for survival and eventual rescue.

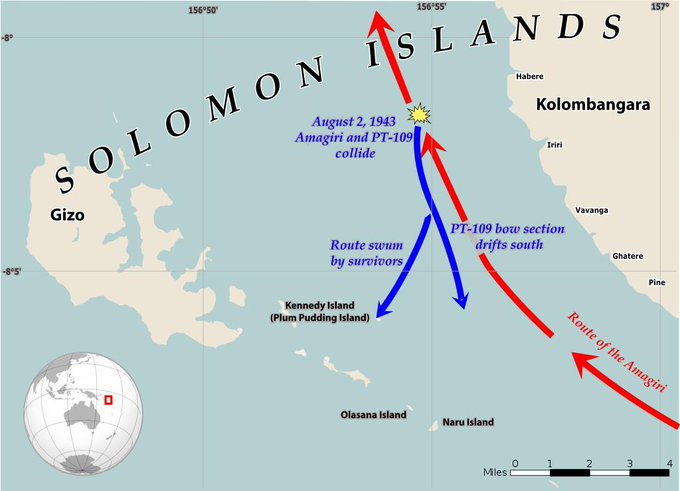

On the night of August 1-2, 1943, 15 PT boats including Kennedy’s PT-109 were sent from their base near Rendova to Blackett Strait to intercept the Tokyo Express coming in from the north to supply the Japanese base at Vila on Kolombangara Island.

The nighttime raid was a total SNAFU for all the reasons I earlier described: torpedoes that didn’t work, wakes that glowed in the dark (and made easy targets for Japanese shore gunners), and radio silence leading to confusion. They didn’t hit much less sink a single thing.

The PT boats that hadn’t shot their torpedoes, including PT-109, were told to go back north into the main channel and wait around in the dark, hoping to attack the Tokyo Express destroyers on their return trip that same night.

So PT-109 is sitting there and suddenly, out of the dark, comes the bow of the Japanese destroyer Amagiri, which sees the American PT boat and intentionally turns to ram the smaller boat, cutting it in half and causing its fuel tank to explode and catch fire.

The Japanese take one look at the burning wreckage and assume all of the American crew must be dead, and drives on. The other PT boats in the area take one look and assume the same thing, and head back to Rendova.

In fact, all but two (which are never found) of the 13-man crew are alive, clinging to the wreckage in the middle of the strait, though at least two of the survivors have serious burns.

They drift for 12 hours, hoping for rescue, afraid to swim ashore to the mostly Japanese-held islands. Finally, in daylight, they swim nearly 4 miles in 4 hours towards shore. Kennedy personally pulls the most seriously wounded crewman behind him.

They finally come ashore at tiny, uninhabited Plum Pudding Island, south of Gizo. This isn’t it (it’s me snorkeling near an island in the lagoon off Munda), but it’s a good idea what the final stretches of that swim might have looked like.

Here’s the real Plum Pudding Island that Kennedy and his crew landed on. See, I told you, just like it. Bet you would have believed me if I said the first one was it.

Problem is, Plum Pudding Island has no fresh water. And the coconuts were all inedible. And nobody was even looking for them, assuming they were dead. The wounded were fading, and if they didn’t find help soon, they were all going to die.

Over the next several days, Kennedy swam out several times on his own to search for help, cutting himself repeatedly on the sharp coral. At times he found himself adrift and semi-delirious on the ocean currents, barely making his way back to his injured crew.

Eventually, on August 5, they encountered two Solomon Islanders paddling a canoe, who worked with local Coastwatchers. At first the natives were suspicious Kennedy’s men were Japanese soldiers and ran away, but eventually the PT crew were able to communicate their situation.

With no pen or paper at hand, Kennedy carved a message onto a coconut for the two islanders to deliver to their PT boat base at Rendova. After a treacherous journey through Japanese-controlled waters, they and the message got through.

The carved coconut message was later turned into a paperweight that President Kennedy kept on his desk in the Oval Office. Today it can be seen in the Kennedy Presidential Library.

Fellow PT boat captain William Liebenow led a night rescue mission from Rendova that picked up the stranded crew. All 11 survivors of the initial sinking were saved. Here’s Liebenow with Kennedy during the 1960 presidential campaign.

The PT-109 story played a very prominent role in Kennedy’s political career, giving him the aura of an experienced war hero. When he was elected president in 1960, members of his crew marched in the Inaugural Parade.

The ordeal did change Kennedy. People who knew him said it was though he had passed through a test, and gained some secret knowledge of himself.

Normally, after losing his boat, Kennedy would have been entitled to return back to safer duty in the US. But in September 1943 he returned to combat duty and took command of another PT boat, PT-59, and led a number of hazardous missions in the Solomons.

In 1944, Kennedy was sent back to the US and hospitalized in Massachusetts for a serious back injury. While there, he was awarded the Navy and Marine Corps Medal for his actions in saving the crew of PT-109 on August 1–2, 1943.

While Kennedy and his crew were still stranded on Plum Pudding Island, the Army was slugging it out in the jungles east of the Japanese airstrip at Munda.

To learn more about this, I met up with Barney, a Munda resident who scours the local hills for relics of the WW2 battle for New Georgia.

Barney was, um, already well into celebrating Saturday afternoon when we linked up. He was, as they say, three sheets to the wind. He cheerfully apologized for his handicap, and welcomed me to his home to view his “collection”.

Barney started “collecting” war artifacts when he found the dog tag of a man named Peter Joseph Palatini. He later successfully tracked down the man, who had not been killed but just somehow lost his ID tag while serving as US Navy airplane tail gunner on the island.

Here’s a “knuckleduster” – a US Army knife grip with spikes for hand-to-hand combat.

Who doesn’t have the wing flaps from an SBD Dauntless diver bomber in his garage? Barney does.

Tail fins from expended American mortar bombs used in the battle for New Georgia, in July and August 1943.

Bayonets, dog tags, and a couple of morphine capsules Barney found, with the powder still in them.

The engine of a Japanese warplane, actually (Barney tells me) manufactured in the US before the war.

Japanese saki bottles, found on New Georgia in the Solomon Islands.

American Coca-Cola bottles, found on New Georgia. The Coca-Cola company actually set up bottling plants in every theater of the war, to give US troops a taste of home. It also made sure the company got its wartime sugar quota and could stay in business.

I asked Barney if he’s got a metal detector. He said he got one from Australia a couple years ago and yeah, it’s great, can find stuff buried half a foot down.

I asked Barney if he ever comes across live ordinance. He said yes, all the time, but he never touches it. One look around his yard makes me wonder if this is entirely true.

Actually logging (seen here on Guadalcanal), often by Malaysian firms, is a big (if controversial) business in the Solomon Islands. But the presence of so much live WW2 munitions spread throughout the jungle can make it a hazardous activity.

Bullets still embedded in tree trunks can damage a chain saw or even go zinging off and injure loggers.

In any case, I said my thanks and goodbyes to Barney and left him to resume his well-earned weekend R&R at the Munda Bar.

Through late July and early August 1943, US troops fought their way through the jungle towards the Japanese airstrip at Munda.

… finally capturing it on August 4 (view from the air today) (*not my photo)

US TBF Avengers on a bombing mission targeted at Munda, in July 1943.

Destroyed G4M “Betty” bomber at the captured Japanese airstrip at Munda.

Through the rest of August 1943, US forces mopped up Japanese resistance on New Georgia, between Munda and Bairoko.

The Japanese airstrip at Munda was rapidly turned into a US air base to support the offensive against the next step in the drive towards Rabaul, the island of Bougainville.

US aircraft based at Munda (on New Georgia) during the subsequent Bougainville Campaign.

Bougainville (circled in yellow) is actually in modern Papua New Guinea, and the campaign to conquer it from the Japanese – which raged from November 1943 all the way to the end of the war (in August 1945) – is outside the range of this thread.

But I did pay a visit to another US airstrip, northwest of Munda on New Georgia, that played a supporting role in that campaign, and is now lost to the jungle.

Hey, that’s an unexploded artillery shell right next to where we’re tying up our boat. What could go wrong?

An old Coca-Cola bottle left behind by US troops in WW2, where the pier used to be for a US airfield in the mangrove swamps of Vonavona Lagoon, northwest of Munda.

I followed this local man and his daughter down what was once a US military access road carved in the jungle from the pier to the airstrip.

Ruins of a Japanese tanker truck in the jungle on New Georgia, in the Solomon Islands. It was destroyed during a US bombing raid.

The tanker appears to have been empty when it was taken out, because whatever hit it punctured the fuel tank and come out this side without causing an explosion.

Wreckage of a US warplane that crash-landed in the jungle on New Georgia, after taking Japanese fire over Bougainville.

I’m told this was a P-40 Warhawk fighter plane (hard to tell, from the wreckage) and that the pilot was killed on crashing, and his body found and returned to the US.

The home of the local family that lives on the former US airstrip, deep in the jungle in New Georgia.

They live on the papaya and other crops they grow on clearings in the jungle. They can’t clear fields by burning, however, because of all the unexploded WW2 ordinance in the vicinity.

Nearly stuck on a coral reef in Vonavona Lagoon, near an old US WW2 airfield in the jungle on New Georgia, in the Solomon Islands. This is where you have to watch out for salt water crocodiles, which can be fast and deadly.

This is nearly the end of my history tour, but I’m going to wrap it up back in Brisbane, Australia, which served as a key Allied naval base for the South Pacific in World War II.

I mentioned that the Bougainville Campaign lasted all the way through the end of the war, with Japanese troops there holding out even as islands behind them, closer and closer to Japan, fell to Allied invasion.

The Australian frigate HMAS Diamantina was commissioned in 1945 and took part in the Bougainville Campaign, and offers a glimpse of what life aboard ship was like during the naval battles to control the South Pacific.

Seamen’s quarters on the HMAS Diamantina, an Australian frigate that fought in WW2 in the South Pacific.

Galley (kitchen) on the HMAS Diamantina, now in dry dock in Brisbane.

Elevator for bringing up shells from the magazine to the main deck gun, on the WW2 Australian frigate HMAS Diamantina.

The main engine room of the WW2 Australian frigate HMAS Diamantina.

Sick bay aboard the WW2 Australian frigate HMAS Diamantina. This would have been a busy and horrible place during the naval battles I’ve described in this thread.

Officer’s wardroom aboard the WW2 Australian frigate HMAS Diamantina. Clubby.

Cabin of the ship’s medical doctor, aboard the WW2 Australia frigate HMAS Diamantina.

Captain’s cabin aboard the WW2 frigate HMAS Diamantina.

The Captain’s chair on the open-air bridge of the WW2 Australian frigate HMAS Diamantina, which joined the Allied fight in the South Pacific starting in 1945.

The radar scope on the HMAS Diamantina – a critical but often underutilized advantage against the Japanese early in the war.

The sonar for the HMAS Diamantina, located right under the captain’s chair on the bridge, for locating enemy submarines.

Depth charges on the aft deck of the WW2 Australian frigate HMAS Diamantina, now a museum ship in Brisbane.

And there’s a reason why we’ve ended up on the aft deck of the HMAS Diamantina, because it was here on September 13 and again on October 1, 1945 that the Allies accepted the surrender of Japanese forces to the northeast of the Solomon Islands.

This was one of the last Japanese surrenders of the war, and brought the South Pacific campaigns I’ve covered in this thread finally to an end.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this journey to these fascinating landscapes and the stories they have to tell even a fraction as much as I enjoyed traveling there and learning about them myself. Thanks.

[…] While the fight for Guadalcanal was won, the battle for the Solomons – and my own trip – was far from over. Click here for Part 3, to continue the story. […]