September 16, 2018

Before it was transferred to Italy after World War I, Trieste – on the Adriatic Sea – was the main port city of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. It was a major center of shipping and commerce, and the self-conscious grandeur the Austrians tried to achieve there is obvious.

My hotel in Trieste, the Excelsior, was one of those glorious piles that harken back to some European golden age (real or imagined) before the Great War.

The turbulent history of Trieste is framed by north, south, east, and west, but begins at its center, in the few fragments that remain of its Roman forum, backed by its old medieval castle atop a hill.

To the east of Trieste lies the Carso, the limestone plateau overlooking the city, and the road across to the distant capital of Vienna. This obelisk, at Opicina (Slovene for “by the cliff”) signified the long journey was over – or just beginning.

To the west, the Adriatic Sea, and Trieste’s old oceanfront passenger terminal, through which people from around the world passed through Trieste, the gateway to the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

One of those travelers to Trieste, when was still part of Austria, was the Irish writer James Joyce, who lived and taught in the city for much of his life.

These people, in Trieste’s monumental plaza (now named after Italian unity) seem to have been transported from that lost Austrian era.

After the Allies’ victory in World War I, and the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Italy claimed Trieste as its prize – and built plenty of patriotic monuments to let everyone know it.

Which brings us to a disused rice-husking factory to the south of Trieste – the site of the only Nazi death camp on Italian soil.

After the Italians threw out Mussolini and switched sides to the Allies in July 1943, the Nazis seized Slovenia, Istria, and northeast Italy, intending to incorporate them into the German Reich.

They sent their SS henchmen down to Trieste to set up shop in the Risiera di San Sabba, a facility they would use to ruthlessly crush any resistance.

This warehouse, which at the time had separate floors, was used as a collection point for local Jews destined for the larger death camps of Auschwitz and Treblinka. (Risiera di San Sabba, Trieste, Italy).

But the main purpose of Risiera di San Sabba was the torture and mass execution of captured Italian and Yugoslav partisans, who were beaten and interrogated in these tiny cells (Trieste, Italy).

The “death room” at Risiera di San Sabba was where such prisoners were thrown to await their execution, usually by carbon monoxide asphyxiation, hanging, or being stabbed by bayonet. (Trieste, Italy)

The outline reveals where the crematorium where their bodies were burned once stood. It was blown up by the Germans when they fled in May 1945, to destroy the evidence of their crimes. (Risiera di San Sabba, Trieste, Italy).

The iron sculpture shows where the smokestack stood, connected to the crematorium by a short underground passage. Many thousands of captured partisans and other prisoners were murdered and disposed of here at Risiera di San Sabba, in the south of Trieste, Italy.

To the north of Trieste lies a relic of a different, more whimsical chapter in history, but one with its own tragic ending: Miramare Castle

Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian (portrait to the left, inside Miramare), born in 1832, was the younger brother of Austrian Emperor Franz Josef. He commanded the Austrian Navy, based in Trieste.

In 1857 he married his 2nd cousin Charlotte, the daughter of King Leopold I of Belgium. Her portrait is set above his bed at Miramare.

During his naval service, Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian fell in love with this part of the coast north of Trieste, at Grignano.

After Max and Charlotte married, they built Miramare Castle as their home, where they served a pleasant posting the Imperial Austrian Viceroys of Lombardy-Venetia.

Meanwhile, Emperor Napoleon III of France (right) was looking for a way to intervene in Mexico, while the United States was preoccupied in its Civil War. He alighted on the idea of getting the Mexicans to offer Archduke Max a throne as their Emperor.

The idea wasn’t quite as crazy as it sounds. After all, the Habsburg family had ruled Mexico, through Spain, until 1700, and there was a monarchist party in Mexico that wanted a ruler they believed could unite the country.

This was a chance for Max to be more than the “spare”, to join the ranks of the other contemporary monarchs whose portraits hung at Miramare.

He signed the accession note to become Emperor Maximilian I of Mexico at this small round table, which was gift of the Pope, at his home in Miramare.

Portraits of Max meeting with a delegation from Mexico, formally inviting him to become emperor (left), and departing for Mexico from the boat dock at Miramar (right). In Miramare Castle north of Trieste, Italy

Here is that same boat dock at Miramare, from which Maximilian departed – never to return to his beloved home again.

Max was in many ways a high-minded humanist – a “dreamer” some called him – who sincerely believed he could rule Mexico nobly and well.

But many Mexicans, led by Benito Juarez, saw Maximilian and the French soldiers sent to keep him in power as foreign invaders, and took up arms in revolt.

From an earlier trip, here are some picture I took of Maximilian and Charlotte’s palace atop Chapultepec Hill in Mexico City:

And here’s a book recommendation on the topic, which is one of the things that drew me to Trieste in the first place.

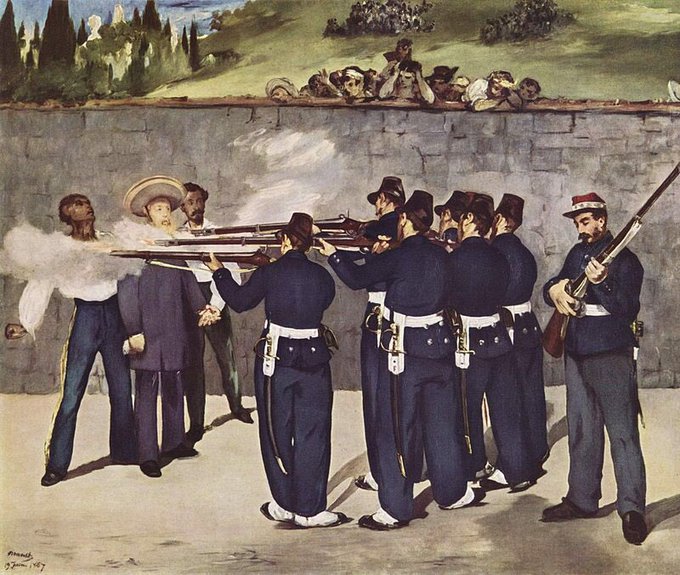

Things did not end well for Maximilian. He was executed by a Mexican firing squad in 1867, an event famously depicted by the artist Edouard Manet. Charlotte, sent home to Belgium, went mad.

But the story of Miramare Castle doesn’t end there. It later became the home of the Duke of Aosta, a prominent Italian military man who fought in both world wars, and served as governor in Italy’s Africa colonies.

Archduke Max’s bathtub, Miramare Castle.

Now fast forward to the last days of World War II in Europe, in May 1945. As Hitler shoots himself in his Berlin bunker, Allied troops from New Zealand are making a rush along this stretch of the Adriatic coast to claim Trieste.

As the Germans bug out of Trieste (and blow up their death camp at Risiera di San Sabba), the Allies set up their military headquarters just up the road at Miramare Castle.

Meanwhile, Tito’s Yugoslav partisans are looking down at Trieste from the Carso at Opicina, equally determined to seize the port for their own. It’s the first big flashpoint of the Cold War.

As a result of the standoff, the whole area around Trieste becomes a special zone divided between the rival occupying powers until 1954, when those zones form the de facto boundary between Italy and Yugoslavia.

Since 1918, Trieste has been a port city cut off from its natural hinterland to the east. But the end of the Cold War and integration of Slovenia and Croatia into the EU is changing that.

Today, Trieste is home to at least one world-famous brand, Illy coffee.

Sunset in the port city of Trieste, Italy.

Leave a Reply