December 13, 2019

From December 13, 2019

I just got back from Qatar, a small country in the Middle East you probably don’t think about much, but should.

Qatar is the largest liquified natural gas exporter in the world, and the richest country (per capital) in the world. It hosts the largest US military base in the Middle East, and is preparing to host the World Cup in 2022.

In recent years, wealthy Qatar has weighed in heavily in political developments and military conflicts across the Middle East, provoking – and successfully defying – the ire of its powerful neighbor Saudi Arabia.

First of all, how do you even say “Qatar”? Foreigners usually say “kuh-TAR” are that’s come to be widely accepted. But the locals say “KUH-tar” or “KUH-ter” which sounds almost like “cutter” but not quite.

Qatar is a desert peninsula that sticks out like a thumb from Arabia into the Persian Gulf. It has a population of 313,000 Qatari citizens and 2.3 million expats from other countries, about 80% of whom live in or around the capital city of Doha.

Humans have inhabited Qatar for 50,000 years, leaving rock carvings behind as evidence. Over that time, the surrounding sea levels have risen and fallen, and the climate found there has changed a great deal.

Today, inland Qatar is mostly flat scrub desert, inhabited by lizards and birds – including falcons and ostriches.

The national animal of Qatar is the Oryx, a kind of desert-dwelling antelope.

But the seas surrounding Qatar are rich in life, ranging from sharks to dugongs (sea cows), lobsters, fish, and pearl oysters.

Throughout history, Qatar’s population – which rarely numbered more than a few tens of thousands – lived along the coast where they fished as well as traded far and wide, from Iraq to India.

They also went diving in the Persian Gulf for pearls, their main export.

Pearl divers – many of them locals, but many more of them slaves purchased or captured from abroad – had to hold their breath for long periods, gather as many oysters as possible, and hope that their shipmates would haul them back to the surface in time.

For part of the year they would fish and dive for pearls, for the other part move inland to graze their flocks of sheep in the desert, or trek across Arabia to Mecca on pilgrimage.

Local chiefs built mud forts at strategic points, and some used them as bases to become freebooting pirates, raiding merchant vessels sailing up and down the Persian Gulf.

This museum in Doha is located in a former slave trader’s home and compound, where captives from pirate raiding were sold as pearl divers or domestic servants. It is dedicated to remembering the role of slavery in Qatar’s history.

Doha itself developed because it was one of the few places in Qatar with good access to fresh water. The well remains a landmark today.

In 1819, the British waged war to subjugate the pirates of the Persian Gulf, and forced them to sign a treaty. These small coastal emirates became known as the “Trucial States” because they had signed a truce recognizing British supremacy in the Gulf.

One historical novel I picked up in Qatar about this period is “The Corsair” by Abdulaziz Al-Mahmoud, which has been translated into English.

The 19th Century saw the rise to power of the al-Thani clan, which still rules Qatar today. The country’s maroon and white serrated flag comes from their banners.

The personal belongings of the first al-Thani emirs shows they had their hands full fending off the Turks, Saudis, and British, all of whom competed to exercise control over Qatar.

This museum in downtown Doha illustrates what life was like for a wealthy urban family during that time, around the start of the 20th Century.

But the early 20th Century was devastating for Qatar, as the ruins of this abandoned fishing and pearling village on the north coast indicates.

The global influenza epidemic of 1918 ravaged Qatar. Then the Great Depression, along with development of the cultured pearl industry in Japan, destroyed the pearl-diving trade, the country’s economic mainstay.

Thousands of people emigrated, in desperation. By 1940, Qatar’s entire population had fallen to just 16,000 people. Yes, 16 thousand.

What changed everything? Oil did. But not as quickly or as easily as you might think.

In the 1920s, the British set up shop here, in this small compound on what was then the outskirts of Doha, to explore for oil. They had found it in Iran and nearby Bahrain, and figured Qatar might be a good prospect.

When the British hired local workers and told them they were looking for oil, the Qataris all assumed that they meant fish oil, because that was the only oil they were familiar with.

They drove the handful of Qatari workers – who were desperately happy to have jobs of any kind – out to the desert in trucks like these, where in 1940 they finally did strike oil. But then World War II broke out, and the British postponed any further operations.

When oil operations restarted, in 1947, Qatar was really on its last legs. This is what Doha looked like then.

That said, Qatar was never more than a marginal crude oil producer, not a powerhouse like Saudi Arabia. Even today, it’s only the 17th largest producer in the world, with just 1.5% of global crude oil reserves.

In fact, if you collected stamps like I did as a kid, the way you most likely first encountered Qatar (much like Abu Dhabi and Dubai) was through the colorful postage stamps they produced, on virtually every topic under the sun.

The oil revenue may have been enough to keep Qatar’s royal family well stocked with fancy cars, but not enough to truly transform the country.

The key moment came in 1995, when Crown Prince Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani (right) ousted his father (right), the ruling emir, in a bloodless coup when he was out of the country visiting Switzerland.

The new emir had big plans for Qatar that involved tapping the offshore natural gas reserves that had been discovered years earlier in the Persian Gulf.

These massive gas deposits were initially dismissed as worthless because they were nowhere near consumer markets. But the new emir borrowed heavily to construct the world’s largest natural gas liquification plant at Ras Laffan, on the northern tip of Qatar.

Converted to Liquified Natural Gas (LNG), Qatar’s gas could be transported by ship to markets around the world, particularly Asia – turning Qatar into the world’s 2nd leading natural gas supplier, after Russia.

Originally the US was also envisioned as a major customer for Qatari LNG, and huge facilities to deliquify gas shipments were constructed along the US coast. But after fracking created a natural gas production boom in the US, these plants were converted from import to export.

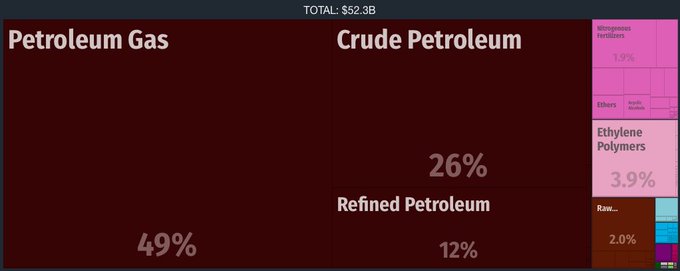

Today, LNG accounts for nearly half of Qatar’s exports, with crude oil accounting for another 26%, and refined fuel and petrochemicals accounting for most of the rest.

Who are Qatar’s export customers? Asia. South Korea, Japan, India, China, and Singapore top the list.

The natural gas boom has catapulted Qatar’s population from around 500,000 to 2.7 million, with most of the increase due to an influx of foreign construction and other workers.

GDP per capita has also taken off, and now ranks among the highest in the world. Given the number of relatively low-paid migrant workers factored into the average, the typical income levels for Qatari citizens is far higher.

Qatar’s sovereign wealth fund has $335 billion under management, and owns Harrod’s as well as large chunks of Volkswagen, Barclay’s, Heathrow Airport, and Sainsbury’s, and large real estate holdings in London, New York, and Washington DC.

Doha’s own skyline has exploded with new ultra-modern skyscrapers, in a new district across the bay from the old town.

The city features an indoor Venetian-themed shopping mall called Villaggio, with gondola rides (and Filipino gondoliers).

Though Doha’s old souk, refurbished in traditional style over a convenient underground car park, remains far more popular with locals.

Qatar’s royal family has invested heavily to turn Doha into a cultural capital to compete with nearby Dubai as a tourist destination, starting with a stunning national museum designed to look like salt crystals formed in the desert.

And the harbor-front Museum of Islamic Art, designed by I.M. Pei and opened in 2008 to showcase the emir’s collection of traditional art from across the Muslim world.

From my visit to Qatar’s Museum of Islamic Art:

Qatar’s royal family has also opened a modern art museum to display parts of their own extensive collection as well as attract shows from around the world.

In fact, Qatar’s royal family is estimated to spend more than £600m a year on art, and Princess Mayassa (who is in charge of stocking the country’s new museums) has emerged as a heavy hitter in the global art world.

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2013/oct/24/qatar-sheikha-mayassa-tops-art-power-list

Founded in 1993, Qatar Airways is one of the fastest growing airlines in the world, and was just rated THE best airline in the world, based on customer ratings, for the 5th year in a row.

And Doha recently opened a glitzy new international airport especially designed to handle Qatar’s large fleet of Airbus A380s, with a capacity of at least 50 million passengers a year – many of them transiting through Doha as a hub to other locations.

In 2010, tiny Qatar won its bid to host the soccer World Cup for 2022 – though the victory was clouded by suspicions that bribery and corruption had played a role in the decision.

To host the World Cup, Qatar is in the process of building at least nine huge new stadiums dotted all around Doha. To cope with the intense desert heat, they will supposedly be equipped with revolutionary (and very expensive) climate control systems.

Because there is no way tiny Qatar needs nine soccer stadiums, it’s reported that several will be dismantled after the World Cup games and donated to other countries.

The 2022 World Cup has focused attention on the conditions of foreign workers in Qatar, many of them poor and from South Asia.

Much of the criticism has centered on the “kafala” system in which foreign workers in Qatar obtain visas through their employers, who often hold their passports, making them vulnerable to abuse.

https://www.theguardian.com/sport/2019/oct/16/qatar-abolish-kafala-january-world-cup-2022

Given the fact that the large majority of people living in Qatar are actually foreign workers – like this gas station attendant from Nepal who I met – their working conditions and rights are hardly a small matter.

One can go on and on about Qatar’s newfound wealth and the museums, skyscrapers, and stadiums being constructed, but that’s actually NOT why Qatar has been in the news a lot lately.

That reason is politics, and like natural gas, it began in 1996 with Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa’s decision to found Al Jazeera, a 24-hour news channel modeled on CNN, but aimed at the Arab-speaking world.

Al Jazeera gained its reputation and popularity during the US War on Terror, but it entered dangerous new territory in 2011 with its live coverage of the Arab Spring. Many rulers in the region saw the channel – and its Qatari royal sponsors – as cheerleading for revolution.

It also threw a spotlight on Qatar’s increasingly active and independent diplomacy in the region, acting as a self-appointed mediator in conflicts from Lebanon to Afghanistan.

When Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi was threatened, Qatar stepped in with arms and money for the rebels, including radical Islamist groups who gained control of much of the country.

When the Muslim Brotherhood took control in Egypt, Qatar was a big supporter – angering Saudi Arabia, which saw the Brotherhood as a threat and supported the Egyptian military when they later ousted them.

In Syria, Qatar backed its own proxies against Assad, often in conflict with Saudi Arabia – which accused Qatar of supporting al-Qaeda affiliated groups – and drawing Qatar closer to Erdogan’s Turkey.

Qatar’s emir also became the first head of state to visit Hamas-ruled Gaza. But Qatar also maintains good relations with Israel, which did not object to the trip, or to millions in Qatari aid – perhaps because it keeps the Palestinians divided and undermines Hamas’ rival PLO.

Qatar also maintains friendly relations with Saudi Arabia’s main regional rival, Iran, which it shares the Persian Gulf gas fields with.

At the same time, Qatar hosts the largest US military base in the Middle East, at Al Udeid just outside of Doha, which serves as the forward headquarters for US Central Command, with over 11,000 US troops on location, and over 100 aircraft.

Obviously Qatar has been playing a complex game of hedging. Sometimes it’s been aggravating to its partners, but other times useful: Qatar has used its relations with Afghanistan’s Taliban to host peace talks with the US, in Doha.

Still, by 2013 the Qataris realized they were getting in over their heads. To send a message they would cool things down a bit, Sheikh Hamad (left) announced he was handing over power to his son Tamim (right), who became the new emir.

It wasn’t enough. In June 2017, Qatar’s neighbors, led by an irate Saudi Arabia, imposed a total economic blockade on Qatar, unless it gave into a number of demands, including shutting down Al Jazeera.

According to former Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, Saudi Arabia was on the verge of invading Qatar, but the US – with its huge military base outside Doha – vetoed it.

https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2018/8/1/rex-tillerson-stopped-saudi-and-uae-from-attacking-qatar

Qatar also helped shield itself from a Saudi invasion by inviting in a contingent of Turkish troops, raising the specter of a broader conflict, instead of a cake walk.

Still, many thought that Qatar would inevitably be forced to cave to its neighbors’ demands. Instead, it ended up weathering the blockade quite well.

Qatar went to great lengths to shore up its relationship with the US and the Trump Administration, including making large purchases of US military equipment.

And now there’s talk that Saudi Arabia may be ready to back down on what has turned out to be a failed gambit to put Qatar back in its place.

Those who are interested in learning more about the blockade of Qatar by Saudi Arabia and its other Gulf neighbors, and how it played out, might want to check out this video:

The same guy also has a good video on how Qatar became so rich from natural gas:

I hope you’ve enjoyed this summary of what I learned on my trip to Qatar this past week, and please don’t hesitate to let me know if I’ve forgotten anything important, or if you have further questions.

I truly appreciate your technique of writing a blog. I added it to my bookmark site list and will