December 20, 2022

Down the Columbia.

It’s time now to scoot back up the Columbia River, like the salmon at Bonneville Dam, to rejoin where we left the other, water-bound leg of the Oregon Trail.

A view of the Columbia River Gorge from the northern (Washington State) bank.

Before the Cascade Locks were constructed around them in 1875, the emigrants on rafts had to brave the difficult Cascade Rapids east of present-day Bonneville.

The construction of the Cascade Locks allowed steamboats to travel up and down the Columbia River, at least as far up as The Dalles.

Both the locks and rapids were flooded with the construction of the Bonneville Dam just downstream in the 1930s.

The Bridge of the Gods, built in 1926 connecting Washington and Oregon across the Columbia River just downstream of the Cascade Locks. It is named after a massive landslide that temporarily blocked the river several hundred years ago and became part of Indian legend.

Freshly caught salmon for sale under the Bridge of the Gods, on the Oregon side of the Columbia River Gorge.

A view of the former location of the Cascade Rapids, now flooded by the Bonneville Dam.

The Bonneville Dam spanning the Columbia River, built in the 1930s as part of Roosevelt’s New Deal, and named for Army Captain Benjamin Bonneville, an explorer credited with charting much of the Oregon Trail.

There are actually two hydroelectric plants at Bonneville Dam, the original one to the south, built in the 1930s, and a second one on the northern bank, built in the 1970s, connected by an eye-catching spillway between them.

Water gushing through the central 18-gate spillway at the Bonneville Dam. During World War II, the dam provided essential electricity for wartime aluminum smelters, shipyards, and aircraft factories in the Pacific Northwest.

Electricity generating turbines inside the north power plant at Bonneville Dam. Although they were running, all we heard was a low hum, and no visible movement.

Fish ladder outside the north power plant, to help salmon and other migratory fish travel upriver to their spawning grounds, past Bonneville Dam.

A view of the salmon climbing the fish ladder at Bonneville Dam. These were big fellas, about 2-3 feet long.

When I was a kid, I had this old (1940s) Disney book where Mickey and Minnie Mouse and their friends travel America by car. The first place they go is Bonneville Dam to see the fish ladders. So I’ve always had it in the back of my mind to come and see it!

Another view of the fish ladders (this time around the south power plant) at Bonneville Dam.

The south power plant at Bonneville Dam, dating from the 1930s. Beside it are locks for ships to pass the dam.

Fish hatchery in the grounds of Bonneville Dam. Salmon, trout, sturgeon, and other fish.

A map at Bonneville Dam showing the migratory routes of Pacific Salmon. They are born upriver, live in the ocean, the return up the same river to spawn.

Salmon eggs growing into baby salmon, on display at Bonneville Dam.

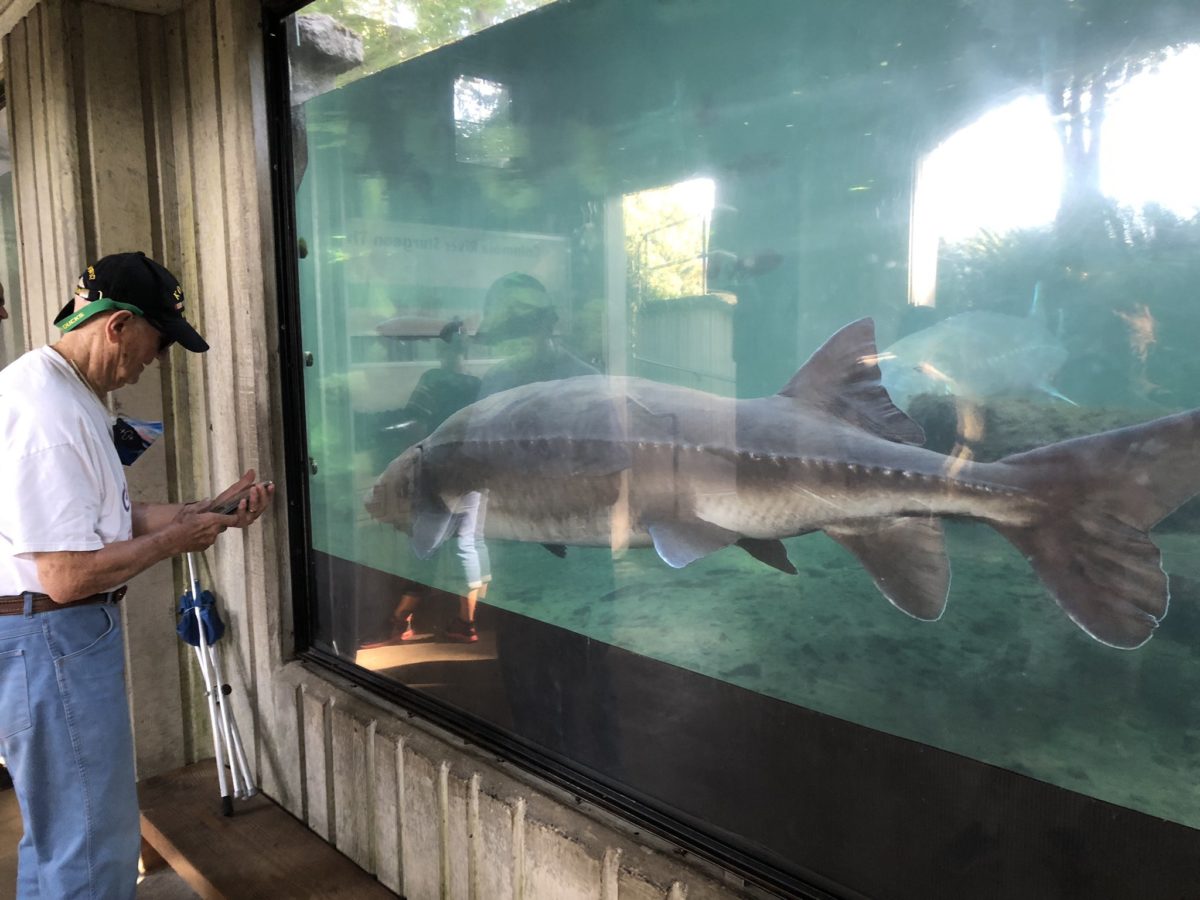

Rainbow trout and sturgeon at the Bonneville Dam fish hatchery.

Viewing some giant sturgeon at the fish hatchery at Bonneville Dam, on the Oregon side of the Columbia River.

Encountering Bigfoot at the Bonneville Dam fish hatchery. He must have thought my son was a fish for the grabbing.

Passing Horsetail Falls, on the Oregon side of the Columbia River Gorge, downriver from Bonneville.

The final destination of the earliest Oregon Trail emigrants floating down the Columbia River was the Hudson Bay Company’s fur trading post at Fort Vancouver (not to be confused with Vancouver, Canada).

Fort Vancouver, just across the river in Washington State from present-day Portland, was the headquarters of the HBC’s fur trading empire in a territory disputed between the US and Britain.

The Hudson Bay Company’s crest at Fort Vancouver, Washington.

During the War of 1812, the British-owner Hudson Bay Company had bloodlessly ejected the New York-based John Jacob Astor’s fur traders from Oregon, and now reigned supreme.

The Chief Factor at Fort Vancouver, John McLoughlin, was under orders to discourage American migrants arriving in Oregon, and offer them no aid.

Instead, McLoughlin – recognizing the inevitable – was generous, helping them recover from their long journey and selling them provisions on credit, to get on their feet in the new land.

The Hudson Bay Company doctor’s quarters and infirmary at Fort Vancouver.

Blacksmith at work at Fort Vancouver, Washington.

The Hudson Bay Company’s counting house at Fort Vancouver, where the fur trade profits were tallied up.

Where did the furs traded at Fort Vancouver go? A lot went to Europe, to be turned into expensive felt hats. But a great many also went across the Pacific to China, where they became mandarins’ robes – in exchange for tea and porcelain.

McLoughlin’s wife – well, common law at least – was the daughter of a Swiss fur trader and a Cree Indian mother. But his home at remote Fort Vancouver was a little slice of Britain.

The formal dining room at the main house at Fort Vancouver was the political nerve center of the nascent Oregon territory. The Whitmans dined here, as did John Fremont (western explorer and the Republican Party’s first presidential nominee).

The fort today is in fact a replica, reconstructed long after the original fort burned down (sorry). But it is based on devoted archeology and research.

After Oregon Territory was ceded by Britain to the US, the Hudson Bay Company eventually closed up shop and turned the land over to the US Army, which operated an important military post there.

Starting in 1911, Pearson Field, on the grounds of Fort Vancouver, became one of America’s oldest operating airports. It played an important role in training pilots for World War I, and later in the “golden age” of record-setting interwar flight.

But it’s finally time to set our eyes on the prize – the end goal of our journey – Oregon City. I’m just sad to hear it’s so boring.

Why was Oregon City everyone’s destination – the end of the Trail? Because the land office was there. That was where you went to stake your claim.

New arrivals typically hoped to start a farm somewhere amid the well-watered land near the Willamette River, which fed north into the Columbia.

John McLoughlin eventually lost his job with the Hudson Bay Company for welcoming the migrants. But he stayed in Oregon City, built this house, and became a successful businessman in his own right. He is considered the “father of Oregon”.

Several beautiful old homes from that period line “McLoughlin’s Promenade” on the high ground overlooking the Willamette River.

Down below is Willamette Falls, harnessed by – what else? – a hydroelectric plant.

Oregon City has a municipal elevator connecting the upper town on the ridge with the lower town by the river.

Looks like someone around here still plays old video games.

Well, we’ve reached the end of the Oregon Trail. Congratulations if you’ve reached it with us.

Time to put away the wagon and give the oxen some rest.

It was quite the journey. And quite the memories for my son and me.

[…] The journey finally comes to an end here, in Part 12: Down the Columbia. […]